’Tis the season for fat pants and even fatter lies told to children about an ancient elf who visits every child’s home on Christmas Eve, delivering presents or coal (pending a behavioral assessment).

As a parent, I love the idea of Santa Claus for several reasons. For one, this myth is the gentlest form of coercion I’ll ever endeavor to use on my sweet babes because, you know, Santa is always watching. Second, I am, in fact, the jolly old soul spreading Christmas cheer, so perpetuating this myth lets me feel uber-philanthropic for one day a year. Third, nostalgia is the chink in my intellectual armor. For an entire month, I am allowed to wallow in traditions of my yesteryear without judgment. Everybody else is doing it. Reminiscing in January would seem unnatural.

Still, we have a sleigh full of reasons to rethink this myth. With more and more parents in my friend circle labeling the Santa myth as “manipulative” and “materialistic,” I’ve taken pause to reflect on my preservation of the grandest lie in history and to research what the experts are saying.

Is the Santa hype coming from the kids or from us? Famous for his Santa studies, Zicklin School of Business Professor John Trinkaus has published at least four studies on the visible reactions of children and parents standing in line to wait for Santa. Each study reconfirms findings from the previous study, with the latest in 2005 verifying with great certainty (82 percent of 300 children’s physical mannerisms evaluated) that most children seem “indifferent” about seeing Santa. On the other hand, he has found that many of the parents or guardians accompanying those children seemed excited (87 percent), leading us to believe that the big Santa sit moment isn’t about the kids as much as it is about the parents. Or as I like to say to my husband, “Christmas is for the kids. And me.”

In a landmark 1994 study, University of Texas at Austin psychology researcher Dr. CJ Anderson interviewed 52 children who had progressed to the point of Santa disbelief. On average, most of these children discovered the truth about Santa by age 7, and these children reported generally positive experiences regarding their realization moment. Interestingly, Dr. Anderson also found that parents reported feeling “predominantly sad in reaction to their child’s discovery.”

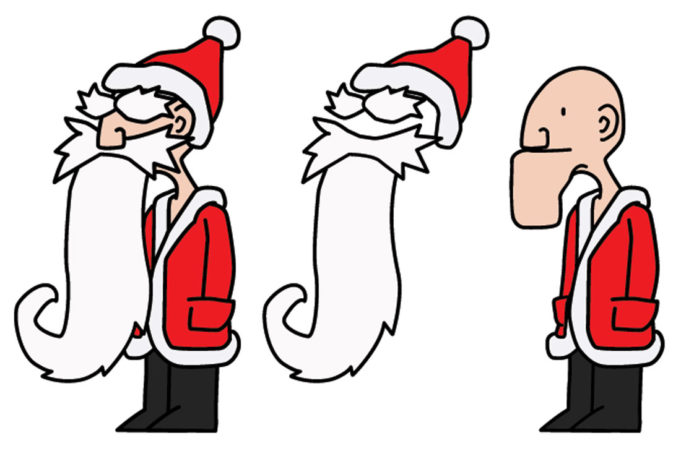

More recently, another UT-based psychology professor, Dr. Jacqueline Woolley, co-authored a piece investigating the contradictory nature of teaching children about magical characters in conjunction with the “long enduring lay notion that children must be taught the difference between fiction and reality.” In 2016, Dr. Woolley shared previous research suggesting that most children start to distinguish fantasy from reality as young as 3 or 4 years of age, when they start to pick up cues and signs that help them distinguish what is imaginary from what is probable. Somewhat counterintuitively, what Woolley found is that increased exposure to live Santas only improved children’s beliefs about the existence of a real Santa, and parents who actively promoted Santa stave off feelings of doubt for longer than if they passively engaged their children in these beliefs.

Across the pond, Dr. Robert Cluley argued that every ounce of energy applied to the Santa mirage reflects the fetishism, ambivalence, and narcissism of adults. Dr. Cluley’s contention is founded on principles of psychoanalysis — a field of study that continues to come under fire, despite its persistence as a viable discipline of psychological study — and pulls from a hefty amount of market research. He says that parents ‘organize a world based on an image they wish were true as if it were true.” Allow me to interpret: We are dragging the innocents down into our delusional underworld.

Kansas State University child development expert Charles Smith can help clarify what counts as good ol’ fashion fun and what edges on manipulation. He once reported to CNN that a parent who drives a child around on Christmas Eve, claiming to see Santa in the sky, and encouraging the child to look while laughing at the child’s effort to see what doesn’t exist is an “abuse of the child’s imagination.” Smith also said he’d be skeptical of any child who continues to believe until ages 10-12, stating that he’d wonder if the child had issues letting go.

While Smith’s advice is helpful, I think that most parents would be dissatisfied with his answer. At what point does any of the Christmas tradition become overly manipulative? If some flannel-flanked Frankie is stressing over touching her elf on the shelf, is that manipulative? If a cookie-making Cameron can’t sleep because he’s checking Alexa for Rudolph’s transit updates, have we crossed a line? And, by the way, isn’t a holiday founded on the conversion of pagans to Christianity inherently manipulative anyway? I ask these questions in jest, but I hope parents consider why holiday spirit — however well-intentioned — is being spread for their benefit more than the child’s. Part of parenting is accepting that our children are growing up. Keeping the Santa myth alive won’t keep my son from growing out of another pair of shoes or my stepdaughter from adopting a teenage tone of voice.

A little part of me is even looking forward to the day both kids figure out the Santa myth for themselves. I still remember the day my 7-year-old self marched proudly down the hall to tell my dad I figured out that Santa’s handwriting was actually Mom’s, and I’ll never forget my dad’s overjoyed response: “Yep. And the Easter Bunny isn’t real either.”