There was a knock on the door, and Callie answered it. It was the mail carrier dropping off a package. Normally, the delivery person just placed parcels on the porch of Callie’s suburban Saginaw home, but since it was November and holiday package thefts were on the rise, Callie merely chalked it up to cautiousness on the part of the postal service. She closed the door and headed back inside. She was barely able to take two steps before there was another knock – and then the sound of a battering ram smashing her door open.

“Police officers stormed into my home,” Callie said, “and had me on the floor, and I’m zip-tied.”

Her three children were upstairs playing video games but “got to be a part of this whole fiasco, which is unfortunate.”

Local music scenesters probably know Callie best by her stage name, Callie Dee, a hip-hop promoter who has put on some of the biggest rap shows in North Texas and with some of the biggest names, including Leon Bridges, Doug Funnie, Krum, DJ Spider-Man, and Alsace Carcione. Charged with possession of a controlled substance – more than 400 grams of Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive chemical in marijuana –– she is reassessing her future. She was in the process of taking her promotions company national. Now her future is less certain.

Upon meeting Callie, your first impression might be “soccer mom,” not drug kingpin or hip-hop mogul. In fact, the Dallas Observer referred to her as “the hip-hop promoting soccer mom,” a title she wore with pride (and turned into a hashtag). She looks exactly like the sort of person who would fit into that suburban housing development she calls home, with its manicured lawns and cookie-cutter houses, not the dark nightclubs where she runs her shows. But not only is Callie Dee one of the most popular and successful hip-hop show promoters in North Texas, she’s an ardent legalization supporter and has been using marijuana to get by in more ways than one for years. Callie had sent the package to herself from a business trip to California. The package was full of cannabis products. Legal in California but not in Texas. Apparently, she had been given some bad information about mailing contraband.

“I was always told that the worst that could happen was they would confiscate the package,” Callie said. “Otherwise, I wouldn’t have allowed it to happen because, you know, I have kids and stuff.”

For an expert opinion, I contacted Chris Harris and Will Hutson, two Waco attorneys who make music videos about marijuana laws in Texas. Two of them – “Don’t Eat Your Weed” and “Pot Brownies” – went viral in 2016, and the duo performed at South by Southwest that year.

“Somebody told her if they find it in the mail then they would just throw it away?” Harris said. “That’s terrible advice. There’s a myth that if something is discovered in a post office, [police are] not allowed to open that package unless they get a warrant. And that is not true. They have dogs in sorting centers, and if the dog alerts, that’s probable cause right there.”

So Callie Dee got to meet some of Fort Worth’s finest. The police searched her house and confiscated the 400 grams and more than $2,000 in cash. The money was everything she had on hand, she said. (She doesn’t believe in banks.) Callie also alleges that when the cops weighed the cannabis, they also weighed its packaging: glass and metal containers.

The singing Waco attorneys have some advice about what to do if you find yourself in a similar situation. Don’t say anything. Well, almost nothing.

“Just say ‘lawyer’ a lot,” Harris said. You can “give your name. They’re in your house, so they probably don’t need your address. [You’re] definitely being detained.”

The right to remain silent, Hutson said, can actually be used against you in this sense: “There’s a case out there … [that] basically says, ‘By me invoking my right to remain silent, that can be used against me in trial.’ … So don’t say, ‘I’m going to remain silent.’ Say, ‘I’m not talking to you until a lawyer gets here.’ That way, you’re invoking your right to counsel and not necessarily your right to remain silent.”

In Texas, marijuana derivatives are treated the same as heroin and other, much harder drugs. Once you’ve extracted the psychoactive components of marijuana, even a misdemeanor amount is now treated the same as heroin or PCP. One of Hutson and Harris’ viral music videos was about this very topic. A pan of pot brownies in Texas is an enhanced first-degree felony: 10-99 years in the penitentiary. It’s a stiffer charge than murder. When the cops add up the weight, they count the flour and eggs since it is now infused with THC. A misdemeanor amount of marijuana can add up to a life in prison once concentrated and mixed with something else.

“The law itself is in massive need of reform,” Harris said. “It’s been this way since the 1970s. Derivatives and concentrates were addressed at a time in the ’70s where marijuana was the scariest thing since Jack the Ripper.”

Despite the fact that marijuana is legal in some form in over half of the country, arrests and frequent prison sentences are common. According to a 2016 report co-authored by the American Civil Liberties Union and Human Rights Watch, more than half of the drug arrests in the United States are for marijuana, and more people are arrested each year for weed than all violent crimes combined. In 2014 (the last year data were available), 73,000 people were incarcerated and another 500,000 people were on probation for simple drug possession. Per the ACLU, $3.6 billion a year is spent on marijuana enforcement and more than half a billion on incarceration alone. Probation fees, lack of employment opportunities, and even difficulty obtaining housing can trap people convicted of even minor drug offenses in a cycle of poverty.

While it is probable that marijuana has many health benefits, scientific studies have been hampered by federal drug laws. Texas lags behind most of the country in legalizing marijuana, even for medicinal use.

Callie asked the officers to pick her up off the floor before her children came downstairs, and the cops respectfully complied, she said. For the most part, she said, the officers were polite and professional.

“I had to tell one of them to shut their fucking mouth,” Callie said, “because he kept talking about how I was as a mother, like, ‘Oh, she was worried about being on the floor, but look at this.’ I had some pipes and whatnot laying out. After the third time he brought somebody over there to tell him, ‘Oh, she was so worried about being on the floor, but look at this,’ I was like, ‘Can you just shut up? We get it, all right? You think I’m a bad parent. Just shut the fuck up now.’ ”

The Fort Worth Police did not respond to our request for comment.

Callie has always been upfront with her kids about her marijuana usage. When she was a child, her parents hid their marijuana use from her, she said, and she wanted to be honest with her children. Her teenage son has tried it (like most teens), but he didn’t care for it, Callie said.

The officers seemed shocked that this suburban single mother was responsible for all of that contraband –– just like people are often shocked to find out she is a hip-hop promoter. Callie said the officers kept asking her who else was involved, who sent the package to her, and how she paid for it. They wanted to know what banks were used to pay for it, she recalled. What they thought was a drug ring was just a single mother buying cannabis products with a medical card in California and sending them back to herself in the mail. It was an act of desperation –– make enough money to support her family while also helping people she knows here who are ill and rely on the products.

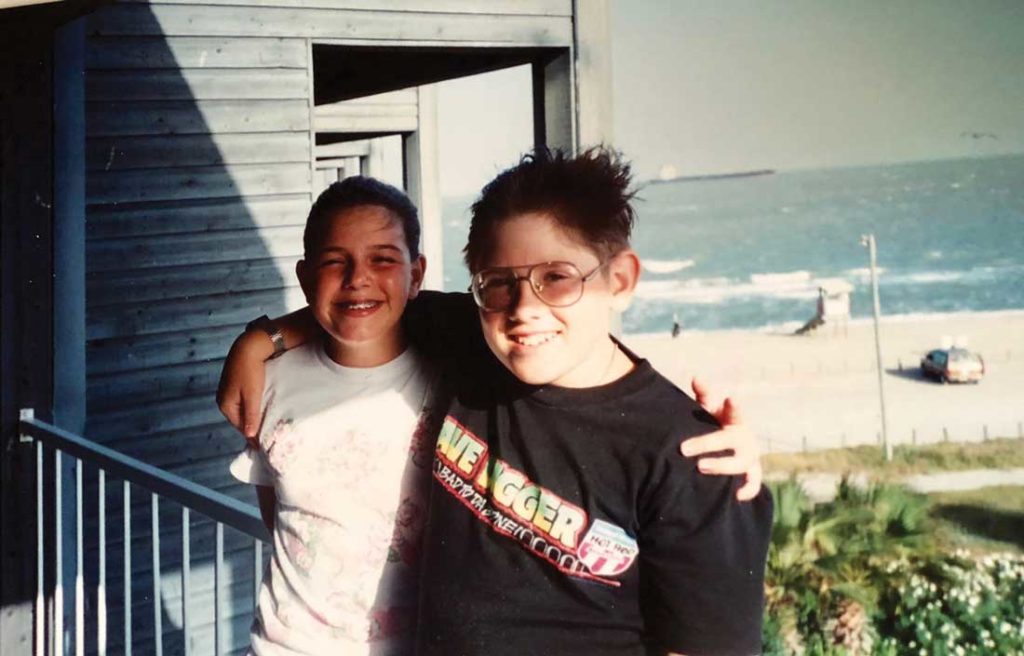

It was a skill she learned at an early age, growing up in a dysfunctional family. Callie said her mother’s struggle with drug addiction and mental illness meant that Callie and her two brothers had to take care of themselves.

“My mother is a drug addict,” Callie said. “You know, we lived in poverty for most of our lives. … Being a person in poverty, you kinda hang out with a certain class of people. Back in high school, I hung out with the hustlers.

“I used to be a really, really great kid, you know, really straight edge,” she continued, “but it got to a point in my life where it wasn’t getting me anywhere. I kind of learned the hustle game. One of the loves of my life was actually a dealer, and he taught me how to make money off of it, so as I got older, to make ends meet, I’d hustle. I’d sell drugs.”

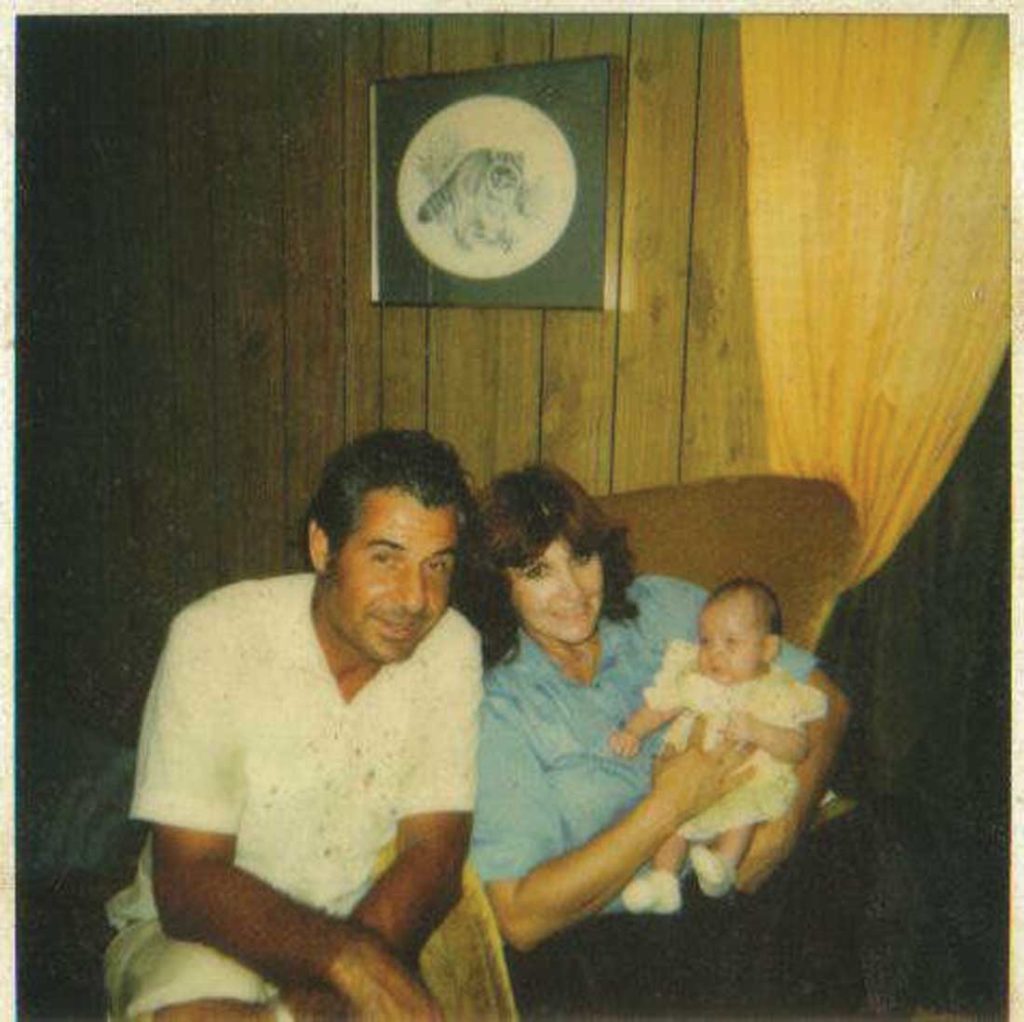

Growing up in a dysfunctional household, Callie said she suffered a great deal of abuse, physical and verbal. Her mother would leave her in the care of strange men to go out, and while Callie has blocked out many of her memories of that time, she believes she suffered abuse at their hands as well.

“I only have bits and pieces of memories,” Callie said, “but a lot of the people that watched me later on were accused of molesting their children. I knew things at an early age that a 4- or 5-year-old shouldn’t know. When you’re that young, it’s not until you get a little bit older that you realize how fucked up it is.”

As a child, she reached out to relatives and teachers, but she said they largely ignored her plight.

“My mother used to beat me until I had bruises,” Callie said. “Her favorite word to use was ‘cunt.’ I was a ‘worthless cunt,’ ‘fat pig,’ you know, really awful things, and I’d try to reach out to people and try to get saved, and nobody would save me.

“She would beat me, and then she would hold me and rock me and tell me how awful her mom was to her.”

Finally, someone at Callie’s school listened.

“I was 11, and I broke down in class one day,” she recalled, “just couldn’t hold it anymore. I went to talk to the counselor. The day before, my mom had slammed me into the glass door. I had some bumps and bruises on the back of my head, and the counselor felt the bumps, and she said, ‘I have to call it in to CPS.’ So, there for a while, Mom behaved herself.

“And then whenever I got older, it was like, you know, then I would sell my mom drugs,” Callie said. “She would allow us to drink at our house. The house became the party house. She would tell me things like how to give head with a condom on, like how to put it on with your mouth, and it was just stuff that you should not be telling your daughter.”

The years of physical and emotional abuse nearly destroyed Callie. Her grades were good – she even graduated early – but her home life was a wreck and she had poor boundaries with men. She was sexually assaulted while in high school.

“I would get into situations with men,” Callie said, “where I realized that I had no way out, so I would just freeze, just let it happen and kind of go to another part of my brain.

“So as a teenager, I was very suicidal,” she continued. “I contemplated it all the time. I was always kind of a wuss, and that also kind of fed into my suicidal tendencies because it was like, you know, I’m not even brave enough to kill myself.”

As a way of self-medicating, Callie turned to cannabis. For a young kid with no self-esteem, it was a way to relax and find her voice.

“I started smoking pot, and I was really anxious,” Callie said, “when I was in front of people, I always replayed everything in my head … like, ‘God, you’re so stupid. Why did you say that?’ Then I started smoking pot. I was able to actually be myself around people without hearing it.”

A few years later, Callie Dee found herself with two children in a loveless relationship and suffering from postpartum depression. Feeling hopeless and unloved, she said she took a bunch of pills in 2010 and lay down to die. She believes her partner, who was holding one of the children, mocked her as she started to lose consciousness.

“He was talking to his mom on the phone,” Callie recalled, “and he was like, ‘Oh, she’s faking it. I don’t give a fuck if that stupid cunt dies. I hope she dies.’

“My baby was right there,” Callie continued. “He was right there, and [the partner] was going, ‘Mommy is going to die, so we don’t have to get a divorce,’ and so I realized he wasn’t going to help me.”

Not wanting to be found dead by her other child, who was asleep in another room, Callie managed to call a former partner to pick up the child. The man called an ambulance before arriving. Her first responders told her this saved her life.

The ordeal, Callie said, led to her finally receiving the professional help she needed. She took advantage of every type of therapy her doctor offered her. She joined a church and helped out with the youth ministry. Eventually, she found the strength to remove her and her children from the toxic relationship.

“I felt like I was stuck,” Callie said, “because, ‘Am I going to be a single mother of two?’ And so I try to fight through it and try to make it work. And he would use the same words that my mom would use. You know, it’s kinda weird how things work, because [the partner used] the same words that my mother would use … so I was a ‘no good, worthless cunt.’ ”

Fearing for her safety, she fled with her baby. She spied an available car seat at a yard sale next door. She made a trade for it and called a friend to pick her up.

“I ran outside because he was trying to push me around and be abusive,” Callie recalled, “so I came outside … . He’s not going to do that with the yard sale next store. My friend pulled up, I put the car seat in the car, got my baby in the car, and we drove off.”

She spent some time in women’s shelters and almost lost custody of her children. Gradually, she worked her way up to the point where she had a home and could continue to work on her emotional and mental health.

On her 30th birthday, in 2012, Callie Dee was hanging out at The Where House, a defunct venue on Hemphill Street on the Near Southside. Her younger brother, singer-songwriter Luke McGlathery, was hosting an open-mic and trying to help promote an at-the-time unknown soul singer named Leon Bridges. Callie was moved by Bridges’ performance and felt driven to become involved in the music business. She started blogging about local artists and promoting shows. A long-time fan of hip-hop culture, she gravitated toward it.

“My first hip-hop show in Fort Worth on a Wednesday, over a hundred people showed up,” Callie recalled. “We didn’t lose money. We didn’t make very much, but we didn’t lose money, so that was great.”

Working as a bookkeeper by day while raising three kids, Callie put all she could into promoting acts and building a promotion business. She took over an existing music promotion company, Red Empire, and started a successful series of hip-hop competitions called Master of the Mic. Callie, said rapper Doug Funnie, “connects with everyone in the community. She definitely puts her best foot forward and puts on for the DFW. Can’t really take that from her.”

Being female in a male-dominated industry has had its challenges.

“I’ve had dudes grope me or, you know, talk to me a certain way,” Callie said, “and I let them get away with it because I didn’t know any better, because that’s how [I thought] men are.”

But as she grew more confident, she started setting limits. Initially there was some pushback.

“I finally got to the point where I was like, ‘I’m not going to let that shit happen anymore,’ and so I’ve set up clear boundaries,” Callie said. “They’ll say one little, slight thing, and you laugh it off. I was the queen of just laughing it off and just moving on. Then the next time, it’s a slight grope of the ass, so I’ve made it pretty fucking clear that I’m done. I used to be given a lot of access. I’ve had some people who thought that I was a certain way, so I’d get all the backstage access. But then once they realized that I wasn’t about that anymore, and all of a sudden I went backstage, access is denied.”

The Master of the Mic series started attracting attention, and as a natural at networking, Callie started making contacts with major industry players and began work on taking her concept national. She was able to quit her bookkeeping day job and concentrate solely on her business. Money was tight, she said, but she was making just enough to keep the lights on. And then, she said, one of her two former husbands allegedly stopped paying child support. Without that $700 a month, she said, she lost her home and once again was in crisis mode. With the man nowhere to be found, things got desperate.

“I ended up staying on my brother’s floor from September to October of last year,” Callie said. “Totally imposed on him. … I had nowhere else to go, so I’m like, ‘I’m staying here.’ We kind of struggled a little bit there.”

To survive, she said, she relied on selling marijuana products. Traveling to Los Angeles regularly for her music promotion business, she would pick up medical cannabis products at dispensaries and mail them back home. It allowed her to provide for her family, move into a house, and help some physically ill people in the process.

“We’re all aging,” Callie said. “I have friends whose parents have Parkinson’s disease, [and] a friend of mine has cancer. [Another] friend of mine just got diagnosed with [multiple sclerosis], so when I went to California, I realized that [cannabis products] were things that could help them. I brought a few samples back with me and gave them to some of these people that have ailments, especially the parents, because a lot of them are baby boomers who were under the impression that smoking pot was of the devil. They don’t smoke but are hurting so bad that they are willing to try something. A lot of times, especially if you have cancer, you don’t want to inhale smoke. That’s where these [cannabis products] came into use.”

After overcoming so much in her life and struggling to keep her family together, Callie Dee then had to explain to her young daughter that Mommy was being taken away by the police. The arresting officers removed her handcuffs for her to hug her children goodbye. One of the officers told the young girl that Mommy would be out before the end of school the next day in an attempt to comfort the child (something that Callie said she greatly appreciated). Her teenage son arranged bail. At the jail, the officer taking the mug shots was as incredulous as the arresting officers. He asked her if she had a boyfriend or someone she was taking the charge for.

“Even in my criminality,” Callie said, “people are astounded by the fact that a female could accomplish such things.”

Callie Dee makes no apologies for what she’s done, but she makes no excuses either. She took a chance to make a better life for her family. She sold a product that is legal in several states, but she knew what she did was illegal. She knew the risk.

At first, she was looking at five to 99 years in jail. Now she has recently been offered a plea deal: deferred adjudication for six months and a $1,000 fine. Her lawyer is looking over the evidence and they will come to a decision at her next court date.

And so often we read about police officers overstepping their authority or abusing their power, but that isn’t the case here. Once they discovered her house wasn’t filled with gun-toting cartel members, the officers, Callie recalled, shifted gears and handled the situation calmly and professionally. But sitting in court waiting to be processed, Callie couldn’t help but notice the disproportionate severity with which a case like hers is handled compared to more serious crimes.

“I’m [out] on $30,000 bond,” Callie said, “so I have to report to a bondsman every week as well. I’m not allowed to consume alcohol. I have to do a urinary analysis every week. I call in every day. Any day I can be randomly chosen [for urinalysis] too.

“There’s really no room for error,” she continued. “There’s no getting around the system. I sat there and watched people who are on their third DWI. One had a child in the car with him when he got pulled over, and then another person had a third DWI with bodily injury. And these people who actually are risking people’s lives had less consequences, if you will, than I did. I even saw a guy that had sexual assault on a minor, and … he’s not even facing five to 99, and he sexually assaulted a minor.”

According to the nonpartisan Pew Research Center, 61 percent of Americans favor the legalization of marijuana. But ask even the most ardent foes of marijuana legalization, and they will likely agree that a single mom trying to make ends meet by selling a few vape pens and some weed doesn’t need to be locked up for nearly a century. As singing attorney Harris said, most marijuana laws are rooted in a time of fear. This is an issue only the legislature can fix.

And the Trump administration has vowed to fight legalization. In January, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a memo rescinding an Obama-era policy encouraging federal prosecutors from bringing charges against citizens for marijuana-related offenses in states where it was legalized.

Despite her current situation, Callie is keeping on like she always has. Her Master of the Mic series is expanding to New York City and Los Angeles. She’s been buying and selling vintage clothing on the side to earn extra money and is working on opening a resale store.

Callie no longer associates with her mother, saying that her instability due to mental illness and drug addiction have created an unhealthy environment for Callie’s children. Callie goes on to say that her father has never been much of an influence in her life.

“That’s kind of how my life is,” she said. “When I was 6, I won a contest with my school, and I got to say my name on [Peppermint Place]. For whatever reason, I wanted to wear yellow socks, and my mom wanted me to wear purple socks. And in my school bathroom, we were arguing – I’m a strong-headed person, and I was just intent on wearing these yellow socks. At one point, I was on the floor of that bathroom, and she was kicking me in her high heels right before I’m about to go on Mr. Peppermint. But that’s the epitome of my life, you know what I mean? Like I’m about to do something really, really great, and like Satan just can’t have it. I don’t know how I survived that and didn’t go on Mr. Peppermint looking like a blubbering fool, but I did. I was able to say my name, but that’s just kind of how my life has been.” l

I shouldn’t laugh but I am. These idiots call themselves activists or leaders in legalization and don’t know even 1/100th of the laws about cannabis. I sacrificed not having kids so I can be a real activist. I don’t feel sorry for the wanna be hip hop promoter weed lady. I feel sorry for her kids for having a cheater for a mother.