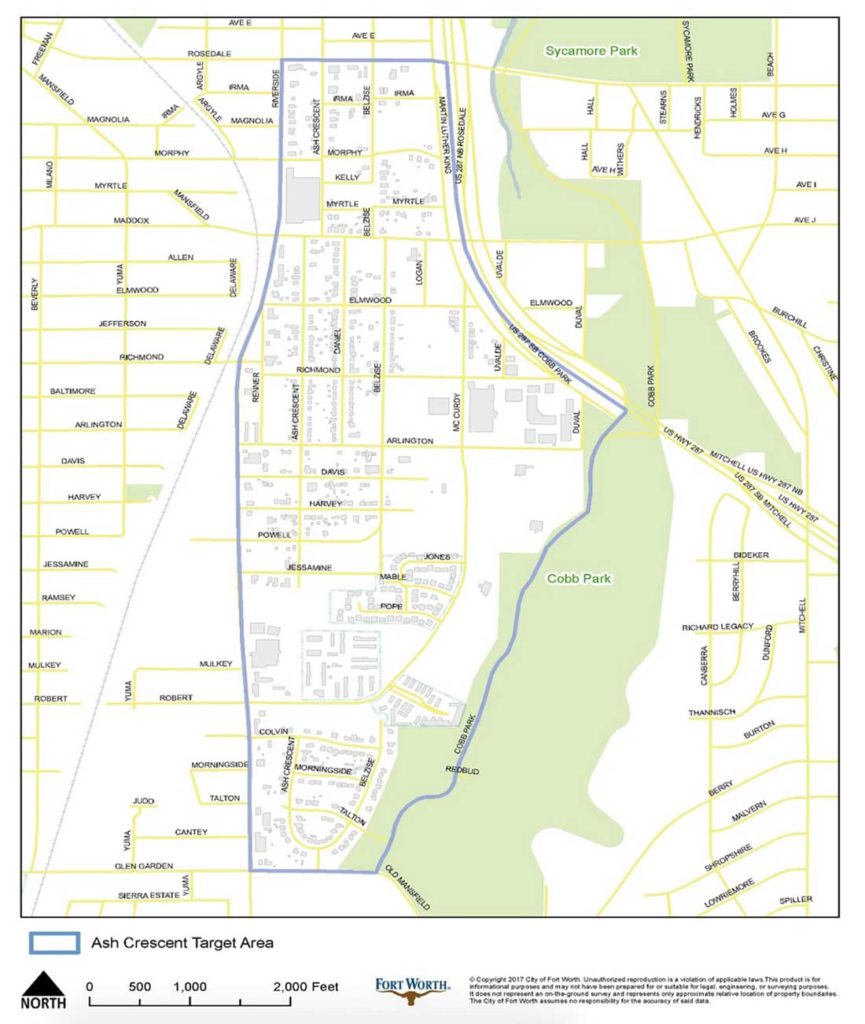

Low incomes, theft, drug sales, and prostitution are problems any forgotten community might face. The issues don’t end there for Ash Crescent, the new name given to the neighborhood in southeastern Fort Worth which is anchored by Ash Crescent Street and South Riverside Drive. During a neighborhood meeting at a local church in February, about 20 residents complained about illegal dumping that blocked streets, 18-wheelers driving down residential roads, and unattended critters in front yards.

“We’ve had problems with horses and goats and chickens in this neighborhood,” one resident said during the meeting at Greater United Missionary Baptist Church. “The horses get loose – in fact, I had to run some off of my yard one morning.”

Fort Worth City Councilmember Kelly Allen Gray plans to stomp out some of those problems with a $2.7 million grant. As the representative of District 8, which encompasses Ash Crescent, she meets with locals and the newly formed Belmont Neighborhood Association on weekends to ensure the money goes where it’s needed most. The area has needed help for some time, the association said. Drugs and gangs have been around for decades and have continued, to some extent, well beyond the 2006 drug bust that made headlines and was later detailed in a book.

Written by former undercover Fort Worth police officer Tegan Broadwater and published by Culvert Publishing in 2013, Life in the Fishbowl presented a first-person perspective of working in Ash Crescent at the height of the drug scourge. The young, clean-cut officer with reddish blond hair penetrated the gang-run neighborhood for the sting. It would have been a tough task for anyone, but it was more so for someone with his appearance.

Law enforcement at the time referred to the southernmost area of Ash Crescent as the “Fishbowl.” That’s because the neighborhood’s layout resembles one and offers few ways for a vehicle to get in and out. Only two streets provide access. Lookouts could alert drug dealers quickly if police approached, which made it hard to successfully take down most of the busiest dope spots, Broadwater told me in an interview. Even today, Ash Crescent is known for its many dead-end streets.

The Fishbowl specifically referred to the few streets boxed in between Glen Gardens Drive, South Riverside Drive, Cobb Park, and East Roberts Street. But the drug bust included all of Ash Crescent and surrounding neighborhoods, such as Polytechnic Heights. The sting – named Operation Fishbowl – led to the arrests of 51 local Crips and the seizure of more than $1 million in drug money. Of the arrested, 41 would receive federal charges.

Although a majority of the indictments were drug-related, Broadwater said the main reason for the operation was to eradicate gang violence tied to the drug trade.

“I worked in narcotics, so I understand the importance of trying to battle drugs, but ultimately the drug dealers you really want out of there are the violent ones,” Broadwater said. “And when you’re dealing drugs in a large quantity, typically you’re going to have the possibility of violence.”

Broadwater planned to put a large dent in the drugs and crime in the neighborhood, which didn’t have a formal name at the time, only a notorious reputation. (The Ash Crescent name originated upon receiving the grant.) He went undercover as Tee, a white guy from the West Side who lost his previous drug connection and needed a new source for cocaine. No need for him to exaggerate his disguise. He doubted a bunch of Crips from Southeast Fort Worth were going to think he was from the ’hood. Aside from wearing his hair a bit shaggier and clothes looser than normal to hide his gun in case of an emergency, “Tee” didn’t change his appearance much. He was able to fit in by not fitting in, acting as an average guy clueless of gang culture. At one point he went into the Fishbowl wearing a red jersey – the color of the opposing Bloods gang – as if he was unaware of the rivalry. The persona worked. He was able to infiltrate the group and experience gang life firsthand.

After the operation ended, criminal cases were handed out in large numbers and dope houses were seized. This came with unexpected consequences. Putting away 51 men, primarily in their mid-20s to early-30s, meant potentially locking up fathers, big brothers, and family breadwinners. Losing such a large number of men, most from Ash Crescent, changed the dynamic of the community, Broadwater said. This wasn’t the first time this had happened. Most of the men he took down were products of generational issues.

“If you go back, you find family lineage that comes up through the mid-to-late 1980s and early 1990s,” Broadwater said.

Members of those families who got involved with distributing narcotics “got arrested and were given federal time,” he said. “When Fishbowl came about, I was dealing with their kids.”

Broadwater calls this recurrence of problems “the cycle” – a cycle of fatherless children, common in high-crime communities. Lack of supervision and discipline can send kids hurtling toward a host of problems.

According to the National Fatherhood Initiative, a nonprofit that works to end father absence, children who grow up fatherless are four times as at risk of poverty, twice as likely to drop out of school, and considerably more likely to commit crime and go to prison sometime in their lives.

Broadwater’s bust leveled a positive impact by decreasing the number of gang members in the area and almost knocking out completely the local drug activity. Over the years, former dope houses were remodeled and put back on the market by the city. However, at the time, he didn’t take into consideration the potential negative effect the operation could have on the youth. This troubled him and motivated him to do more for children. Shortly after the completion of Operation Fishbowl in 2008, he linked up with Gary Randle, a former police officer and a cofounder of H.O.P.E. Farm, a nonprofit and after-school program that provides children of incarcerated parents with recourses such as mentorship, meals, and after-school activities. Randle has been working with children of incarcerated parents for more than 25 years. He told me he started the organization not long after he visited a Texas prison as a police officer and saw how African-Americans were disproportionately incarcerated. They made up 80 percent of the inmate population for that particular prison, he said.

In the state, African-American males constitute 32 percent of the overall inmate population but make up only 12 percent of the state population, according to Prison Policy, a nonprofit advocacy group that researches mass incarceration and criminalization. He felt it was too late to help the people already locked up but believed he could make an impact on the children.

Randle and the organization’s other cofounder, Noble Crawford Jr., started H.O.P.E. Farm in the Morningside neighborhood in 1990 and opened their facility in 1997. They accept fatherless boys, starting at age 5, and try to help them stay out of trouble, complete homework, and take Bible lessons. They even go so far as teaching the boys table manners and how to properly greet someone, such as shaking their hands and looking them in the eyes. Randle and Crawford started with two renovated crack houses and now own a large building, situated just south of downtown. Broadwater admired the faith-based organization’s work and donated the profits from his book sales to it.

Broadwater, Randle said, “saw that those guys he was arresting were guys who came from the same cycle.”

Ten years have passed since Broadwater’s Fishbowl operation. He visited the area a few years after the bust and noticed improvements from his 18 months spent working undercover there. Many of the dope houses he took down were either renovated or demolished and replaced. He talked to a few people and found some didn’t know what had happened in their own backyard.

Still, the area hasn’t been able to remedy its problems or repair its reputation. Currently about half of Ash Crescent’s population lives below the poverty level. Unemployment is double the citywide average. And only 26 percent of the adult population has a high school diploma, according to Fort Worth’s Housing & Neighborhood Services Committee, which provides oversight for federal entitlement programs and affordable housing development. The committee’s January report shows the area is still a hotbed for crime. The rate of crimes against persons there is triple the citywide average. A drug bust alone couldn’t save the area, but the grant from the city has some potential, my sources tell me.

Last year, Fort Worth’s HNSC targeted the historic Stop Six area, another underserved neighborhood similar to Ash Crescent, and has seen some progress. The neighborhood was granted $2.5 million to redevelop Cavile Place apartments, local schools, and more. Cameras were installed on street corners to combat crime.

City officials have discussed similar initiatives to improve Ash Crescent. Streetlight repairs are underway, a new neighborhood patrol officer was assigned, and plans to install cameras have been proposed. Problems such as crumbling pavement on the streets will have to wait for now.

“Based on the conditions of these streets, we could put the entire [$2.5 million] into streets, and it still wouldn’t make a dent into what needs to be done,” HNSC director Aubrey Thagard told the Belmont Neighborhood Association in February.

Thagard said the streets could easily cost around $6 million to repair and that some are already considered to be failing inspection by city transportation officials. But Thagard reassured residents that the grant money would go to other, more pressing needs.

Another concern for the area and Fort Worth as a whole is education. A study from Read Fort Worth, the city’s initiative to have all third graders reading at grade level by 2025, reports that 75 percent of students struggling to read in the third grade never catch up and are four times as likely to drop out of high school. Gleniece Robinson, a former library director for 18 years who said she is now transitioning to a new role in education, hopes city leaders can find a solution to enhance education.

Currently, only about 30 percent of third graders in Fort Worth are reading at grade level or above. The two elementary schools closest to Ash Crescent report even lower reading percentages, according to Read Fort Worth. Only about 13 percent of third graders are reading at grade level at the two elementary schools, both in the Polytechnic Heights neighborhood, according to the report.

“Across the city of Fort Worth, grade-level reading is significantly low,” Robinson said. “I don’t know the contributing factors, and that’s why we need the community to talk to us.”

Perhaps the most active voice in Ash Crescent is Rev. Barry Harper, pastor for the Greater United Missionary Baptist Church located near the corner of Ash Crescent and Jessamine Street. Though he grew up in the neighborhood, he returned only a few years ago after moving out in his 20s. He remembered a tight-knit community when he was a child. Neighbors were like family, they looked out for and corrected one another’s children when needed, and everyone knew everyone else’s names, he said. But things eventually deteriorated.

“You played with everybody, and everybody was familiar with one another,” Harper said. “The neighborhood changed as gangs and drugs took off in the 1980s. A lot of people’s kids had got caught up – myself included.”

Those troubles are still prevalent, Harper said. He added that he sometimes hears gunshots at night and can foresee many other problems. He said he is trying to work to counter the negative changes that have plagued the area over the past few decades. He is the founder of the Belmont Neighborhood Association, which often meets at his church. City officials use the meetings as a medium to inform members of the community about recourses the city can provide to them.

He said the effort that Gray and other city officials have made has impressed him. She and others have continuously showed up, spoken, and listened to the complaints and concerns. It was Gray who advised neighbors to create a neighborhood association, Harper said.

Gray said she is committed to community revitalization. She has made progress in attracting housing around Renaissance Square, located near Cobb Park on Renaissance Drive. People in her district said she is known to knock on doors and speak with homeowners unannounced.

Broadwater, too, was excited about the improvements and the money allocated to the area. After being embedded in the Fishbowl for so long, he said, he was able to meet lots of good people living in a rough environment.

“That neighborhood was so war-torn, but there were so many individual good people in there,” Broadwater said. “They deserve to have a safe place to live.”

The hopes of community leaders, members, and city officials have been high throughout the improvement process, Harper said. Maybe one day, the neighborhood’s poor reputation will fade among its residents, but its story will continue to be read – and possibly watched.

Broadwater’s book might soon be brought to the small screen. Recently, Los Angeles-based screenwriter and director Sutton McKee wrote a pilot series for Life in the Fishbowl. Impressed by the storyline, McKee acquired the rights to the book last year. Broadwater said he had offers before, but McKee was the only writer who told the story in a truly “humanistic” way and understood the purpose behind the book.

Scott Bernstein, one of the main producers behind Straight Outta Compton, the biopic about the famous rap group N.W.A., has also taken notice. Bernstein and McKee may work together to bring the Fishbowl story to life, Broadwater said.

Perhaps all of the improvements made in recent years may serve as a reminder of how much the neighborhood and its residents have overcome.

I would love to see the movie about this story. It makes it even more interesting knowing that it was in Fort Worth and all the great things that are coming out and being changed. The Best part is not just that that the officer help cleanup the neighborhood but he’s actually giving back in ways that would last a life time in a childs Life. This is Great Story and I’m sure will make for an awesome movie.