During her time as the highest-ranking diplomat in Cuba, Vicki Huddleston faced down Fidel Castro at a party, provided thousands of otherwise isolated people with a way to learn more about the outside world, and won awards with an Afghan hound she named after the city of Havana — all while few women held positions of power within the State Department. She was there in 2000 when Elián González showed up floating in the ocean and when the first prisoners landed at Guantanamo Bay in 2002.

And while she could be relaxing in retirement at her home in New Mexico, she’s now on another diplomatic mission: to warn America about the danger of U.S. policy toward Cuba. Huddleston served under Presidents Clinton and George W. Bush as chief of the U.S. Interests Section in Havana, and, earlier under President George H.W. Bush, she was in charge of the nation’s Cuba policy at the State Department. She has witnessed the see-saw of U.S.-Cuba relations, with Democrats traditionally pushing for more open channels and Republicans flexing on the prospect that continued embargo and punishment will lead to regime change.

Her memoir, rushed to press in response to waning sanity in Washington, serves as a primer on recent history and points to bad omens of the past threatening to repeat themselves — or worse.

“It is well past the time that we stop making Cuba a glaring exception to the way we engage with countries around the world whose political systems we oppose,” she writes in Our Woman in Havana.

She adds later that by maintaining an economic embargo, “we undermine both countries’ political and economic interests, deprive our country of a potential strategic ally, and create unnecessary division among our allies.”

Just 90 miles from the Florida coast, this is the neighbor we should be fixated on, she argues. It’s a fraught scenario playing out on the global stage, and yet the foreign policy under the Trump administration projects a chilling forecast. Cuba is returning to close relations with Russia and moving into a tighter bond with China. The governments of those nations, Huddleston points out, are no friends to the U.S.

And with the president giving Secretary of State Rex Tillerson the axe and aiming to replace him with CIA Director Mike Pompeo, diplomatic turnover contributes to greater uncertainty.

Cuba is set to undergo elections that could lead to a succession of power away from President Raúl Castro, who rose to the top not long before his older brother Fidel died. The date of the planned transition has been a moving target, however, and with the United States clenching its fists rather than extending a hand, hardliners in the island nation’s Communist Party leadership aren’t likely to entertain reforms.

Reporter: In the 1990s, when you first got to Cuba, there were very few women diplomats.

Huddleston: In fact, the State Department discriminated against women until about the ’80s. It was considered really a man’s profession, and it was very East Coast and often seen as elitist — and then they realized this is no way to represent the American people. There has got to be a broader and deeper organization with women and minorities. And so they began to change, and that is when I went in, in ’77, which was the beginning of the change. Women were just coming in to high positions after 20 years. When I was in charge of the Office of Cuban Affairs from ’91 to ’93, I was the only woman office director at the time in the Western Hemisphere. There were relatively few [female] ambassadors, too.

Did you do anything to help break the glass ceiling?

There were a couple of women who were in the generation before me, the very first ones, that had a class action suit, but I don’t really think I did anything myself, specifically. Hopefully, I did a good enough job to make it seem as though it would be reasonable to have women in high positions. … But we have had Hillary [Clinton] and Condoleezza [Rice] as the secretaries of state, and assistant secretaries of state, and far more women ambassadors than there used to be, so this is getting rolled back a bit now.

There’s one story in the book where you have to outrun private security guards at a mine, and a whole chapter about your distribution of thousands of transistor radios to the people of Cuba against the wishes of the revolution leaders. You’re kind of a badass and a risk-taker. Why approach it this way?

I think it is my personality. If you go back, I was handing out these little AM/FM radios, and members of my staff who wished to — they were not forced to — were doing the same, and I loved it. At that time [there was] no internet, no cell phones, books were expensive — Castro said that they weren’t censored, but they weren’t available. So most people who had radios didn’t get news from outside because they weren’t strong enough to pick up the signals. So here was this little radio. Everybody loved it and wanted it — from kids to, as you read in the book, a security official. It was, ‘OK, I can have access to news and information.’ … Cuban people really wanted them. I did not want to stop. Fidel did his best to stop me, however.

Was it dangerous?

Not in Cuba. Cuba is an authoritarian state, so, you know, we were enemy number one. We were listened to. We were watched. No one was tailing my car when I went out in the countryside, but they knew where I was. If the car broke down, someone would be finding it very fast. And there is just not much crime in Cuba. So Cuba is safe. In Mali and Haiti, it was, in fact, dangerous. My car was shot at. It had a bullet hole in it. In Mali, we were in the way north Sahara Desert where the Salafast were operating, and there were land mines, and there was a possibility that you might encounter them, although we always had Mali military with us, so I was never particularly worried. But those are much more worrisome and dangerous spots. And foreign service officers who served in Iraq and Iran and Syria and places like that — that’s really dangerous. More senior foreign service officers have lost their lives than generals in the United States military.

So why do it? Why is this work important to you?

I have to admit it was great fun, but what was important to me was to represent my country. It was such an honor. To meet people abroad — I liked learning about people in different countries, and I liked listening to them, and I liked helping them. I really like the idea of making a difference.

Explaining the U.S. diplomatic mission in Cuba is tricky. You have the title of ambassador because you served in that post in other countries, but during your time in Cuba as the highest-ranking diplomat, you were only allowed to be chief of the United States interest section, right?

The official name was “principal officer.” But the myth that we had no diplomatic relations with Cuba is a myth. We were in our old embassy building, which is now the embassy. It is a beautiful glass building on the Malecón. But I was the first foreign ambassador to go to Cuba since the 1950s, ’60s, when we broke relations. I told my staff they could call me ambassador, and when I did that the Cubans called me ambassador, because they liked the idea of having someone of higher rank. And also their person in Washington was a former ambassador. It’s all reciprocal, so the Cubans are in their former embassy on 16th Street, and people called him ambassador.

And now we’ve sent the most senior person we have ever sent to Cuba [Philip Goldberg]. He was our ambassador in the Philippines. But that is the only good thing. I was there in January. The gates of the embassy are locked. There is a chain around them. Nobody is coming in and out except the employees. We usually issued 20,000 immigrant visas a year, and we’re now not issuing visas for families to go see each other or for business or for exchanges. … They’re not doing any public diplomacy. We’re very limited on who is available to do reporting, and Cuba is about to go through a transition — or a succession, which is probably a better word — from a Castro for the first time in almost 60 years. And we don’t really have the staff to know what is going on.

When you wrote the book, the assumed date of the transition was February. In December, the Cuban government officially postponed the presidential appointment for the successor to Raúl Castro. Now the date has moved to April. Is it out of the question to think the election won’t happen?

The local elections are underway now. But, with the U.S. threatening, it is not out of the question. In fact, that might have been the real reason they pushed it back. They said they pushed it back — and it’s a valid reason — because the elections had to be pushed back from the devastation from Hurricane Irma. And if the elections are pushed back, then there is not a national assembly, which technically chooses the council of ministers and the next president. So that is a legitimate reason to push it back.

On the other hand, it gave Raúl Castro time to negotiate a deal that he will soon sign with Russia, in which Russia will take over from Venezuela the operation of the Cienfuegos oil refinery. So that is very important because, with Venezuela becoming bankrupt, Cuba is losing a source of petroleum and a close ally, and it looks as if they’re going to return to Russia and China. And China is Cuba’s largest foreign trade partner, and Russia and China are set to provide Cuba with military training and military equipment.

Why is that bad for the United States?

Russia and China are not our best friends. They are our competitors. We have different approaches, and China has never been aggressively in our face in the Western Hemisphere, but China is very much expanding in Africa and could very much be a competitor for minerals and influence in Africa. Russia is actually the danger. Russia is not a friendly country to us. They interfered in our elections, and they will try to do it again. They don’t appreciate our kind of democratic system that we have, and they feel that NATO and the United States are a threat to their hegemony in Eastern Europe. So if Russia can have a foothold in Cuba, then if we do something in Europe that they don’t like and feel is threatening to them, then they have the possibility of countering us in Cuba, i.e. the missile crisis. Kruschev put the missiles in Cuba, but the deal the committee arranged was that we would not invade and we would take our missiles out of Turkey. That was the real key. So you see, the relationship plays out in the strategic balance in Europe.

Do you think that people in the United States today really have an understanding of the history with Cuba and this bigger global consequence of our relationship?

Yes and no. Yes, in that they are very much aware of Cuba because everybody knows the Bay of Pigs. Everybody knows the missile crisis. Many people remember little Elián found floating in the inner tube in the Florida Straits. Many people remember the shooting down of two civilian planes by Cuba. And many people remember Alan Gross and their five spies — or heroes, as you wish — who were incarcerated in the United States. So since the U.S. is always having this tense, fraught relationship with Cuba, I’d say that people probably know as much about Cuba as you could expect. Although maybe not as much as Mexico. Cuba still is our third-closest neighbor. It’s water that separates us rather than a border.

I think what they don’t grasp, and that is not surprising, is the issue of U.S.-Cuban relations is surrounded by myths, lies, and misunderstandings. First of all, most Americans, when I say that I was head of our diplomatic mission in Cuba, they go, ‘No, we did not have a diplomatic mission in Cuba.’

They don’t understand that Cuba is a matter of domestic politics. Essentially, Al Gore lost the presidency because of this little kid. … Clinton decided to send back Elián if the courts agreed, but he thought that was a way that he could escape political damage. It turned out to be the worst decision, because it took the courts six months, and then it went to the Supreme Court to send back Elián — and so then the Cubans had el voto castigo, the punishment vote, and they were very active against Gore in not providing financing and then stopping the recount of the hanging chads. Gore lost by 500 votes, and had he had a few Cuban-American votes, he would’ve won Florida and he would have been president.

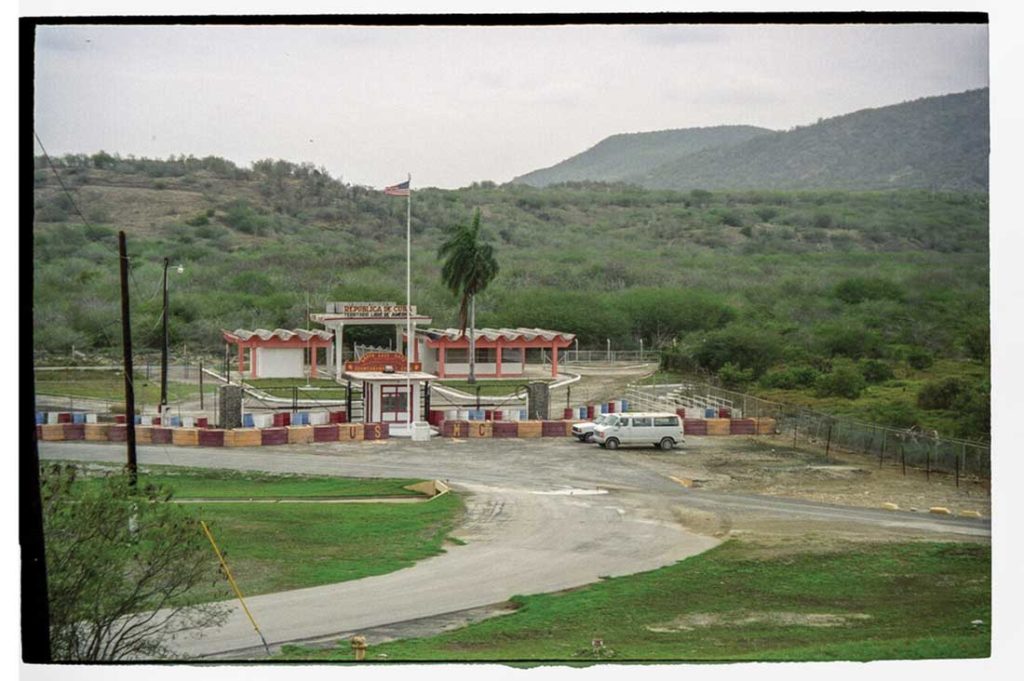

You were also there during the opening of the war detention in Guantanamo Bay. How do you view that?

Nobody, no country in the world, including our allies, was interested in holding those combatants who were captured in Afghanistan by our troops. There were some from other places as well, but they were all basically associated or thought to be associated with Al Qaida. … We did not want to bring them to trial right away, because we did not want them back on the battlefield. And in Cuba, in Guantanamo, according to the treaty, Cuba retained sovereignty, but because the base was run by the U.S. military, Cuba laws did not apply, nor did the United States’ — only military laws. So it was the perfect place. And a long ways away from the battlefield in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

When Guantanamo operations later became exposed, it became less perfect. Do you agree with that?

The unlawful combatants, first of all, remained incarcerated for much longer than anyone might have imagined. The war was over, and they were still incarcerated. And part of that, of course, was the fear that they would go back to their old ways, and we didn’t want more Americans killed. So you can see why that happened, but it still makes us look pretty bad. And the second part of that is, in essence, they were mistreated, and that leaves a blot on the United States’ history and may turn out very badly when U.S. military personnel are captured, because perhaps they won’t be treated like they should be under the Geneva Convention.

It seemed like you got fairly adept at tackling both the Cuban and U.S. media. Why it is important for diplomats to understand the media?

Some ambassadors — and to me, it is a mistake — will publicly criticize the leader of a government by name. You are sent to a country to have a relationship with them, whether they’re friendly or unfriendly, and if you criticize the government, particularly by saying that Fidel Castro is whatever, then what kind of relationship are going to be able to have? And how can you adequately represent your government? I mention in the book that after I went to this big rally that Fidel Castro held against me, with 20,000 people, for handing out of the radios, I came back to the intersection, and one of the human rights activists was waiting for me and he said, ‘Be careful Vicki, because we want you to stay here.’

Do you have any observations about the state of the media today?

The media is really standing up. They are exposing fake and false news, and they’re not being intimidated when President Trump scorns them or tweets against them. … Unfortunately, it is never pleasant to be in that kind of situation. And I think both the media and the foreign service are in the same situation. Both of them are kind of scorned by the president and this administration. Entré into the foreign service has fallen precipitously. I don’t know whether that has happened in the media, but that is what scares me the most. Because both of those professions are really essential to our democracy.

Are there any similarities between the way Fidel Castro treated and talked about the media and the way Donald Trump does?

Autocrats generally don’t like the media. And Fidel liked total control of the media because he wanted to ensure total control of Cuba. And in a way, I think that President Trump — who, of course, is working within a democratic system, so he can’t have that kind of total control — what he really doesn’t like is criticism. And that is, as the media has said from time to time, sort of the nature of a would-be autocrat.

Is there a way that our citizens can drive a different relationship with Cuba, or do we have to ride this out until something else changes in our country?

First of all, people can still go to Cuba, and they should. … If Americans will keep traveling to Cuba, that will help Cubans continue their entrepreneurial activity, which leads to an open society. Secondly, the tragedy of Cuba is that there are five laws that mandate the embargo. So it makes the policy a presidential policy.

The American people do need to speak up. This policy is not in our national interest. How can we have a country that is 90 miles off our shore that is our enemy? That is crazy. We need all the Caribbean to be our allies and friends. This is our backyard. We need to see economic and political development, and that helps our own security. Instead we have just neglected it. We have just got this whole issue about the Caribbean and Cuba wrong, and by getting it wrong we jeopardize our national security because we open the door to China and to Russia.

But people don’t understand how much it is against our national interest. And certainly, unless they go to Cuba, they don’t understand how much the Cuban people are suffering. The embargo has kept food and medicine from Cuba by cutting off supplies from foreign companies that have U.S. subsidiaries. And it has kept Cuba isolated. Because of the communication part of the embargo, it’s been hard for radio and television to hook up with Cuba. We are our own worst enemy in Cuba.

This story was originally published in the Santa Fe Reporter.