A couple of weekends ago, artists, writers, and activists from across the state and beyond congregated at Shipping & Receiving Bar in the spirit of DIY culture for the 2K18 Fort Worth Zine Fest. The zine and music festival, now in its third year, is organized annually by artists Chelsea Bonham and Sarah Avakian, who cite the feminist Riot Grrrl movement as inspiration.

“We both came from the same community of DIY ethos within the punk scene,” Bonham said. “It was important to both of us to create a safe space to promote self-published artists and thinkers.”

Although self-publishing can often carry negative associations – particularly in literary circles – it has been a cultural force since the advent of writing. In fact, seminal authors by the likes of Martin Luther, Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Jane Austen, Marcel Proust are known to have distributed self-published works. As a distinct mode of self-publishing, zines, in a way, came from outer space when mid-century science fiction enthusiasts, who were shut out of mainstream publications, began to share their comics and short stories with one another via cheap mimeograph-printed magazines.

A couple of decades later, it was punk rock, with its politically-conscious, “anyone can play” attitude that largely shaped zine culture as it is understood today. Access to photocopiers meant that any punk fan with little more than paper could issue out music reviews, gossip, and social commentary in quickly-assembled booklet form.The “Riotgrrrl” movement developed in response to the male-dominated punk scene and carved out a space for the female voice.

Synthesizing paper craft and activism, young women marked, folded, cut and pasted their way into disseminating not only their personal expressions, but also a feminist discourse that up until that point had been largely confined to academic circles. Bonham and Avakian’s Zine Fest acknowledged this socially and critically conscious tradition with the inclusion of vendors like the anarchist Emma Golden Book Club and Austin’s MonkeyWrench Books, a radical bookstore that dedicated their table to simple, donation-only social and economic justice zines with titles like “The Abolition of Work”.

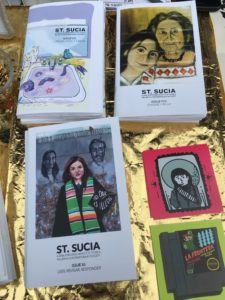

Facing some space constraints, the two organizers opted to highlight DIY artists and groups “that are actively resisting oppression and injustice in their community,” Bonham said. Among the participants was the San Antonio-based,”St. Sucia,” which explores the private lives of young Latinx women through submitted photographs, illustrations, essays, and poems that are then compiled into a simultaneously candid, vulnerable, and irreverent social archive.

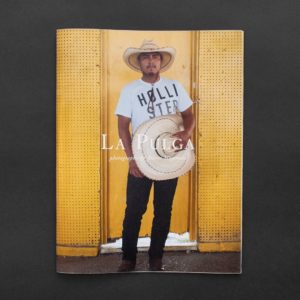

Other highlights included The Dallas Coloring Book Experiment’s whimsical study of downtown Fort Worth parks, Brie Underhill’s meticulously drawn comics, and Raul Rodriguez’s Deep Red Press,that chronicles Texas photographers from across the state. Zine Fest had no shortage of quality offerings, but perhaps most impressively, the festival offered a radically inclusive, culturally vibrant space.

“I think Fort Worth has a lot of questions to ask itself right now,” Rodriguez said. “What kind of city does it want to be? There are so many communities not being recognized that I think can contribute so much to its growth and development. I just hope [zine] culture continues to grow here and that [Zine Fest] can be a prominent yearly event for zine makers from all over to stop by, distribute, sell and be recognized in Fort Worth.”