Nowhere in the Bible does it say, “Thou shalt not kill political careers.” If Tuesday’s primary election leaves a political body count among lawmakers who have gone along with the controversial school voucher system pushed by Gov. Greg Abbott and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, a lot of the credit (or blame, depending on where you stand) may go to the 2,000-member Fort Worth-based Pastors for Texas Children (PTC).

Through community meetings held across the state, PTC, founded in 2013 by Baptist preacher Charles Foster Johnson, has worked to gin up support for public schools and to target lawmakers who have stood as a threat to said schools’ constitutionally mandated funding. The pastors view vouchers as benefiting families who can already afford costly private schools and feel there are other problems with the plan as well.

The vast majority of the state’s more than 5.3 million schoolchildren are from families that must rely on public education. Those who favor a voucher system say it would make public schools better because they would have to compete with private schools for students and taxpayer dollars, but members of PTC (and others) aren’t buying it.

The voucher proposal, which opponents often refer to as a “scheme,” floundered in the 2017 legislature, but it has failed before only to be resuscitated by politicians. A 13-member commission to study the school finance system was born out of last summer’s special session, and the panel was directed to deliver its recommendations to the Legislature by Dec. 31. It is likely that vouchers – also called “education savings accounts” or “tax credits” – will resurface yet again during the 86th Legislature when it gets underway next year on Jan. 8.

“What we have in our lieutenant governor is someone who essentially wants to privatize public education and manipulates his Senate members toward those policies,” Johnson said. “So until we elect enough senators who tell him no, the voucher policy’s going to keep coming back like a bad penny.”

Though there are voters who do support the idea, there is a question of just how many and whether lawmakers have been duped into thinking that the majority of their constituents favor a school voucher system when maybe they don’t. Last March, questions arose after a school choice group flooded the offices of lawmakers from mostly rural areas with letters bearing the names of constituents – some of whom were known by the lawmakers to support public schools and who claim to have never participated in any on-line pro-voucher petitions.

By taking on “Big Ed,” state lawmakers who are facing challenges to re-election may be – we’ll find out Tuesday – falling headlong into a political pit. The danger isn’t just from the statewide network of pastors, many of whom have spouses or other family members who work in public schools and whose congregations include current and former school district employees. The threat is also coming from a number of powerful advocacy groups, including the Texas Association of School Boards, the Association of Texas Professional Educators, Texas Parent PAC, and the Center for Public Policy Priorities. As well, there are business leaders who fear that reducing funding for public schools may negatively impact the future workforce.

Lawmakers’ problems don’t end there.

A rift has been growing within the Republican Party, which dominates both the Texas House and Senate. For weeks during last year’s legislative session, animosity intensified against the Texas Freedom Caucus, a small group of mega-conservative lawmakers that had formed in February. One of its members is District 60 state Rep. Mike Lang of Granbury, a Tea Party favorite who has backed some versions of the voucher idea and whose campaign website states that “the choice of education needs to be in the hands of the parents.” Lang is now embroiled in a bitter re-election fight against fellow Republican Jim Largent, Granbury’s school superintendent. (A lesser-known Republican, Gregory Risse of Coleman County, is also on the ballot for that seat but is not actively campaigning.)

The race, considered to be among the top to watch in the GOP primary, is reflective of the acrimony within the party.

Earlier this month, Largent pulled out of a candidates forum hosted by the Republican Party of Hood County after Tea Party activists who had infiltrated that group’s leadership adopted – and actively publicized – a blistering no-confidence resolution against him. Largent and his supporters responded by hosting their own event on the same night as the forum, billing it as the “Common Sense Conservative Republican Rally.”

Largent drew the larger crowd, as evidenced by photos taken from different angles at both events. Lang’s appearance at Granbury City Hall drew fewer than 50 people, while one estimate put the number of attendees at Largent’s come-and-go affair at Revolver Brewing at several hundred. But that didn’t stop Lang’s former campaign manager and former chief of staff, Zachary Maxwell, now coalition director for the ultra-conservative group Empower Texans, from posting on social media a cropped photo of the Lang event that omitted rows of empty chairs with a claim that Lang had spoken to a “packed house.”

Although Johnson said the PTC isn’t coordinating with public school advocacy groups, they all are working toward the same goal: replacing lawmakers who support vouchers with those who don’t.

“I think we’re going to turn it in the 2018 elections,” he said of his pastors group and others who oppose vouchers. “I do think we have the ability to change the face of Texas politics. I think the secret is educating communities about the threat to public education. A church leader is a spokesman. A church leader has a constituency built in. A pastor is a community leader. He already has a platform. He already has people following him on Facebook and followers on Twitter. And when we can educate that pastor as an advocate for public education, we get a powerful spokesperson for public education. Democracy’s a beautiful thing.”

Ninety-five of the House’s 150 seats, all of which are on the ballot this year, are currently held by Republicans. Twenty-seven Democratic incumbents drew no challengers, but only 10 Republicans were so lucky.

In the Senate, 20 of the chamber’s 31 seats are held by Republicans. Fifteen Senate seats are on the 2018 ballot, and all but one –– the seat held since 1993 by Democrat Royce West of Dallas –– are contested.

Charles Luke, executive director of Spiritual Care Network of Tarrant County and coordinator of the Coalition for Public Schools, of which PTC is a member organization, feels confident that change is coming.

“The business community is going, ‘OK, we don’t like extremist politics,’ ” Luke said. “ ‘We don’t like you trying to spend our time and our tax money on issues that don’t resonate with us, are bad for business, and aren’t going to be helpful in educating our populace to be a strong participant in the business community.’ So that message, I believe, is going to be sent pretty loud and clear by business support. A lot of these extremist policies you’re seeing coming out of the Senate –– and we’ve got some House members that support them –– I believe that’s going to be over with before too long. I believe the pendulum is swinging back to a more reasonable, rational approach to public policy.”

If Tuesday brings a swing of the pendulum, the church leaders will have worked to achieve that change in a way that is unique in light of bitter bipartisan political divisions both statewide and nationally. They did not engage in personal attacks or angry confrontations, nor did they publicly support one candidate over another. Whatever political careers they may have snuffed out, they killed with kindness.

•••••

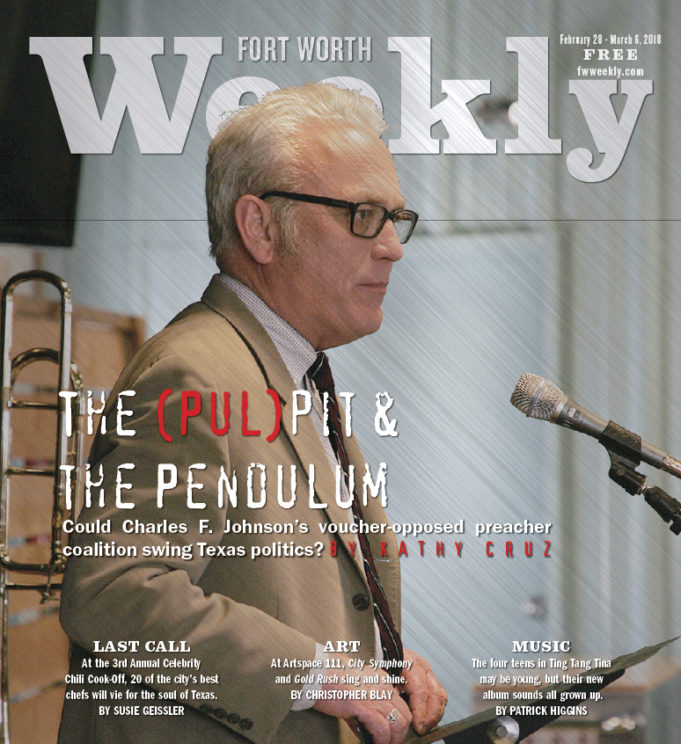

Shortly before lunchtime on Wednesday, Feb. 14, vehicle after vehicle pulled into the parking lot of The Table Community Church, located in northeastern Tarrant County across from Boswell High School, part of the Eagle Mountain-Saginaw school district. Standing in springlike weather just outside the door of The Effie Center, a building on the church campus where an after-school program is provided for teens, was Johnson. He greeted school and government officials and others as they arrived for one of PTC’s community meetings. Inside, a five-piece student jazz band from Boswell performed while attendees queued up for a catered Mexican buffet and then filled every seat, about 100 them. Fort Worth Mayor Betsy Price, Fort Worth Superintendent Kent Scribner, and several candidates for public office were among those in attendance.

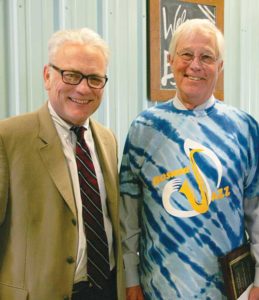

The hour-long pep rally in praise of public ed involved remarks from Luke and several other spiritual leaders. It ended with the presentation of a plaque to District 99 State Rep. Charlie Geren for his support of public education. Geren is being challenged in the Republican primary by Bo French. Democrat Michael Stackhouse is also seeking to unseat him.

With PTC’s community meetings, which will continue even after Tuesday’s election, Johnson aims to show appreciation and support for those currently working in the state’s public school system while encouraging attendees to show their support of public schools at the polls. PTC’s mission includes promoting social justice for children and working to advance legislation aimed at that goal. As a 501(c)3 nonprofit, the organization doesn’t endorse specific candidates.

“We endorse public education for all children, fully funded, particularly on the early grade level, and we oppose the privatization of it –– that is, using our tax dollars to subsidize private education for affluent people,” Johnson said. “So all over the state we’re going into communities with this message, and we’re telling them to vote. Vote for public education. Study the candidates. Determine who supports public education and vote for that candidate. And take 10 other people to the polls with you to do the same.”

Though some have described the coordinated push as an anti-Tea Party movement, Johnson said that is not the case with PTC.

“We’ve got lots of Tea Party folks,” he said. “Most smart Tea Party people, why would they want the government expanding into their private schools through a voucher? We encourage people to vote. We’re building civic engagement, rallying the community to get behind the public schools and to vote for a House and Senate member who will do the same. It’s that simple. The voucher is government intrusion into our home and private schools. It’s wasteful. It’s an entitlement. There’s no accountability attached to it, and so conservatives oppose it. If someone calls themselves a conservative and is pro-voucher, he’s stolen the term and is not using it correctly because conservatives stand for limited government and fiscal accountability.”

With many private schools being religion-based, Luke said that the voucher system would threaten religious liberty, despite claims to the contrary by lawmakers.

“Religious liberty is a huge piece of Pastors for Texas Children,” he said. “We believe that if the state starts giving money to church schools, then the next step is the state’s going to tell that church school what curriculum they can use and the next step is to tell them what they can and cannot preach in the church school and what they can and can’t say in their congregation. We just don’t want the state getting their fingers into a church school that way.”

Opponents say that only district and charter schools offer true accountability and transparency. And, while proponents claim that vouchers would give students from low-income families a greater opportunity to attend private institutions, those private schools will still be able to pick and choose who they accept, PTC members point out.

TCU Political Science Professor Jim Riddlesperger said it is “easy to understand” the argument that forcing public schools to compete with private institutions would make public schools better. But that doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.

“Even if you give vouchers of a couple thousand dollars to a family, does that mean that they’re going to be able to send a child to a $15,000-per-year private school? The answer is, probably not,” Riddlesperger said. “And so how many people does it really impact to have a voucher system? The answer is, probably not that many.”

The school voucher concept is “complex,” he said, and “not really just a liberal-conservative issue. … The voucher system, we need to be careful not to overclaim what it can do, because it also has the potential to take some of the better students out of public schools, thereby diminishing the opportunities of the students who remain. It also has the potential of driving up the cost of public education when you take students out of public schools and give them vouchers to attend private schools. So there are all kinds of related issues on the voucher system.”

Luke said that PTC’s get-out-the-vote effort has been criticized by some who feel that the church leaders’ public advocacy is inappropriate.

“They say that about educators, too,” he said. “They say, ‘I don’t think teachers or school superintendents should be involved in politics. You’re getting paid with taxpayer dollars.’ And then the politician turns around and says whatever they want to say, and they’re getting paid with taxpayer dollars.”

With the well-being of millions of school-age children at stake, “for me to tell a minister, ‘I don’t think you should advocate for public schools on a policy level,’ it would be unconscionable not to advocate for children,” Luke said. “I think a minister that won’t advocate for children is derelict in his duty. Sometimes there have actually been political policies proposed to eliminate food programs for poor kids. So when there’s policy that literally takes food out of a kid’s mouth, you need to be down there, Pastor.”

Luke said that 93 percent of children are educated through public, not private, schools and that the public school system “impacts your life every single day,” he said. “We’re taking on all these social issues and all these education issues and trying to get kids ready to work, to go to college, to participate in our economy.”

Ryan Baer, pastor of Ridglea Presbyterian Church in Fort Worth, speaks out against vouchers through letters to lawmakers and newspapers. He is particularly interested in seeing how the District 10 senate race will shake out. Incumbent Konni Burton is unchallenged on the Republican primary ballot, but there are two candidates for that office on the Democratic ticket – both are public ed supporters. Beverly Powell is a longtime Burleson school district trustee, and Allison Campolo’s mother supported the family on her teaching salary when Campolo’s attorney father represented clients pro bono.

In 2014, Burton, a former Tea Party activist, won the senate seat held by Wendy Davis before Davis’ unsuccessful gubernatorial run, winning first place in a five-candidate primary and then defeating Democrat Libby Willis in the November election. Considered in Republican circles to be a “rock star” (as one publication put it) at the time of her election, Burton voted for Senate Bill 3 last year, which Baer described as “the latest push toward a voucher bill.”

As for why there has been such a strong push among some lawmakers for school choice, Baer said, “As the old saying goes, follow the dollars and look at who is underwriting the re-election campaigns of these folks and look at what their interests are and what their particular worldviews are, and I think you will find very quickly that there are some very deep pockets in this state that make healthy contributions to these folks. Power comes in two forms: dollars and numbers. And I think we’re starting to see an awakening here on the numbers side, and I’m interested to see what the primary season brings.”

Baer feels bothered by the disinterest of some at a time when, in his view, public schools are in jeopardy.

“There seems to be an attitude of ‘Well, they’re not my kids,’ and I find that unconscionable,” he said. “That little third-grader that I’m helping with his math, he may someday be my CPA or my physician, and I need for him to receive the best education that money can buy, at taxpayer expense. That’s part of our social contract as Americans, as Texans. It’s vital to our shared collective future.”

But are kids receiving the best education that money can buy, or is a lot of that money going to overpaid superintendents and others? Those who favor government-funded school subsidies argue the latter.

A piece posted online last month by Empower Texans denounced the “bloated education bureaucracy” that lines the pockets of administrators and school vendors while teachers are underpaid and homeowners pay exorbitant property taxes. The editorial warned that “liberals are working to hijack the Republican primary at the expense of students, teachers, and taxpayers.”

Johnson feels that the bloated bureaucracy argument is “weak” and that the oligarchy is in Austin rather than in the state’s 1,100 school districts. He believes salaries for Texas superintendents are “extremely modest” – and he’s right, since they’re around the $154,717 national average – considering that most of these educators are in charge of budgets that are in the millions of dollars and oversee hundreds, if not thousands, of students and school district employees.

“Schools are already woefully under-funded,” he said. “You would have poor children going to public school and more affluent children going to private schools underwritten by the public treasury. So you’re going to continue to produce racial and economic apartheid, all the while dumbing down the electorate. Obviously, democracy depends on an informed public. And one of the reasons for the privatization of public education is the oligarchy doesn’t want the general populace being educated. That’s the result if a voucher bill passes.”

Johnson isn’t the first to suggest that the school voucher system has racial undertones.

Last summer, the American Federation of Teachers and the Center for American Progress described the school voucher system as having “racist origins.” Their report detailed how, more than six decades ago, officials in Prince Edward County in Virginia sought to avoid racial integration through vouchers. Voucher critics say the report illustrates the possible consequences of the Trump administration’s support for federal investment in the spread of voucher systems.

TCU’s Riddlesperger said that Texas is “a majority minority state” where Hispanic children have made up the largest student demographic for about the past five years, and that trend is only going to grow.

“The face of Texas politics is already changing and is changing rapidly – and that’s going to continue,” he said. “The single biggest issue in state politics in terms of funding is always public education. It’s kind of the core function of states. And the really weird thing is, a bunch of the funding for public education comes, not from the state, but from local independent school districts.”

*****

As he navigates discord in the political arena, Baer is trying to set an example for his three sons on how to communicate with others effectively and respectfully when conflicts arise.

“Conflict is the means by which the best ideas can rise to the top,” he said. “And that’s part of what makes our democratic process, when it works, so beautiful. But how we respond to conflict tells a lot about who we are. We’ve lost our ability to vigorously debate, and everything has become instantly personal. I hold no personal ill will toward the governor or the lieutenant governor. As a matter of fact, I’ve tried to make a habit of praying for them, praying for their families, for their protection, for their guidance. Same thing for our president, for everyone who is tasked with the enormous responsibility of leading. I’ve discovered that when you’re praying for someone, it’s awfully hard to resent them.”

Luke said that he has dealt with contentious people many times at community meetings held by PTC across the state. He recalled a recent meeting in Central Texas during which a minister “disagreed in a little bit of an arrogant, contentious manner.”

What PTC members typically try to do in those situations, he said, “is be patient, be kind, and understand that that particular person just had a different opinion. We have to get to that place in our society where it’s OK to disagree with what’s being said and to express that, and that results in civil discourse, not name calling.”

Baer said he uses his pulpit routinely to remind his 400-member congregation about early voting and Election Day, just as he reminds them of other things that impact the community, such as when a new school year kicks off and school zone speed limits are again in effect. In his view, reminding his congregation to vote is part of being a community leader.

“I’m the grandson of a POW,” he said. “Every time I go to the ballot box, I think of the sacrifices he made.”

Baer offered an example of why every vote matters.

“One of our elders is former City Councilman Zim Zimmerman, who lost re-election last year,” he said. “There are about 100,000 registered voters in District 3 in Fort Worth, and I believe there were 7,000 votes cast, and [Zimmerman] lost by 600. And that pains me greatly.”

Baer was close in his recollection. The number of votes cast last year in the race between W.B. “Zim” Zimmerman and Brian Byrd was 8,034. Zimmerman netted 46 percent of the ballots cast to Byrd’s 54 percent, losing the seat by 686 votes.

Largent, the school superintendent hoping to oust Lang in next week’s primary, wrote in a 2016 online article commemorating “Make Education a Priority” month that Patrick was elected lieutenant governor in a 2014 runoff against David Dewhurst with the votes of just 3 percent of the state’s eligible voters. That means that 97 percent of Texas voters didn’t vote for him.

Riddlesperger believes that vouchers could be “the bathroom bill of the 2018 elections.”

Dan Patrick, he continued, “was kind of the father of that bill as well.”

However, Riddlesperger isn’t convinced there will be a big backlash against lawmakers simply over school vouchers.

“While voters may consider education policies when they cast their votes for legislators, that’s certainly not the only issue they’re going to be thinking about,” he said. “They’re going to be thinking about public transportation. They’re going to be thinking about their taxes. They’re going to be thinking about public parks and their maintenance, and so forth.”

The question may not be whether some voters will be focused on other issues besides public education but rather how many of the state’s more than 700,000 school employees and other public school supporters will turn out at the polls, possibly having the same kind of impact as Patrick’s 3 percent.

There seems to be concern that this may happen.

Last month, Attorney General Ken Paxton issued a non-binding legal opinion in which he questioned whether any “educational purpose” is served by school districts that promote or facilitate voting. This brought a halt to some school districts busing to the polls students who are old enough to vote. Shortly after Johnson’s community meeting at The Effie Center on Feb. 14, Paxton’s office announced that cease-and-desist letters had been sent to the Brazosport, Holliday, and Lewisville school districts because of activities that Paxton had determined amounted to “unlawful electioneering.”

The attorney general’s actions seemingly were in response to an initiative pushed last year to school districts across the state by Texas Educators Vote. It was a campaign that encouraged school boards to adopt resolutions promoting voting among school district employees and students. Emboldened by the January opinion, Empower Texans quickly kicked off its “ISD Whistleblower Project” through which letters were sent to school district employees, encouraging teachers to rat out their colleagues.

Field days, it seems, aren’t just for schools. They are also for social media.

That campaign resulted in a #blowingthewhistle backlash of tweets – thousands of them – from public education supporters who mocked Empower Texans while “blowing the whistle” on teachers who have performed selfless acts, such as providing lunch money for children whose accounts were empty.

The mockery continued when the organization’s General Counsel sent a letter to Splendor school district employees warning them that using school “recources” to transport students or employees to polling places would violate the law and stating that “the Texas Whistleblower Act protects pubic” – emphasis ours – “employees.”

But while that initiative has been viewed by many as laughable, it has also been interpreted as an effort to suppress the vote and intimidate teachers.

“They want low voter turnout so they can keep getting re-elected,” Luke said of some incumbents who have taken an unpopular stance on public education and other issues. “That’s personal self-interest at the expense of you and me, and we’re not going to put up with it. It’s just time. Some of these folks don’t realize that their days are numbered.”