Just two blocks away from the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Stuart David’s “In Full Swing” hangs in the lobby gallery of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. The 1938 painting is kinetic, with outbursts of colors and odd forms. Inspired by the staccato beats of the swing jazz that was popular at the time, the composition is full of the kinds of improvisations that are signature to the style of swing. In Focus: Nina Chanel Abney at the Modern, Abney’s paintings contain the same kind of energy and dynamism found in “Swing,” and they both tap into the culture of their time. It is no surprise that Abney’s work is sometimes written about in the context of this, one of her many connections with works of modern art.

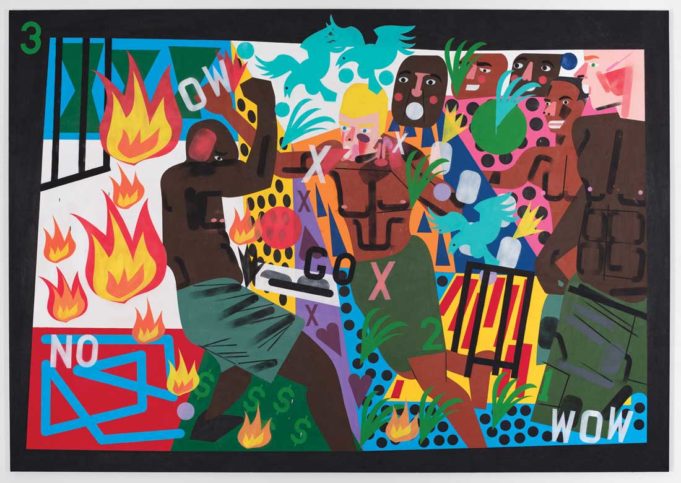

There are three works in Abney’s exhibition, one on each of the three north walls of the Modern’s Focus galleries: “Hobson’s Choice” to the left, “Black and Blues” in the middle, and “Untitled, 2017,” the largest of the group, to the right.

Working intuitively on spray-painted panels, Abney sifts through pre-cut stencils, applying each stencil one at a time, sometimes over pre-painted areas of her tableaux. Some spaces are blocked off using tape and painted as the composition builds. There are subtle residual ghost shadows around figures and symbols as they angle across Abney’s surfaces, hinting at how they were constructed.

The paintings all share common symbols, like a bird, the letter X, and figures whose noses are sometimes made of heart shapes. Abney’s work develops around current events, and politics, protests, and popular culture combine to conjure up a sense of the present. She even references the emoji-laden text message exchanges between her and her friends, with some of those symbols becoming part of the lexicon of shapes and structures in her work. In this way, Abney’s paintings are fresh and evolving, making them a sort of living record of the artist’s experiences and responses to the world.

Reading Abney’s paintings strictly as a coded language of symbols or as political narratives is tempting. The dollar signs in “Hobson’s Choice,” littering the floor below the feet of a boxer, plus the black bars to the right and left of the fight scene, or even the riotous flames burning in the right third of the painting, could be read as a commentary on an unstated conflict just below the surface. With heads and bodies of spectators looking on from above the fighters, it feels as if we are part of what’s happening, onlookers to some perverse manifestation of the raging political battles and the social discourse of our time.

Amid the rich vocabulary of shapes and symbols in Focus, Abney manages to construct vivid signifiers that are freeze-frame vignettes of what’s happening out in the real world. As I walked the length of “Untitled, 2017,” Abney’s 24-by-7-foot painting, I became part of the crowd of protestors, naked and with signs raised, shedding any sense of decency or decorum for the unstated cause. Signs with pink faces compete with text-laden ones, and X’s strategically censor immodest figures in one space while silencing the mouths on the figures of others. There are no fixed meanings across Abney’s panels. Black bird shapes that carry an ominous connotation of death and evil in one painting transform to sky blue, cloud-like wisps in others. But where this flux could invite ambiguity, there is enough within the gestures and compositions of each scene to give the symbols context. Hearts become noses, ovals become faces, and combinations of triangles and rectangles transform into bodies. Even when they are fully articulated, as the boxers are in “Hobson’s Choice,” there are still sections of bodies left undeveloped, creating ambiguous relationships between symbols.

The flatness of Abney’s painted landscapes and figures is the artist’s push back against the conventions of painting that insist on molding figures and objects in such a way as to show volume, depth, and light. These conventions are useful in rendering scenes that prioritize a connection to reality and true likeness, holding this connection as paramount to understanding how we see a complex world. In breaking from these rules, Abney reveals truths by reducing her figures and objects to their fundamental geometry and basic color patterns, making only subtle suggestions to meaning. In this way, we connect to the work on a primal, almost instinctive level, tracing our connection back down an evolutionary trail to when humans first recreated the world with lines, shapes, and color.

Focus: Nina Chanel Abney

Thru Mar 18 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 3200 Darnell St, FW. Free-$10. 817-738-9215.