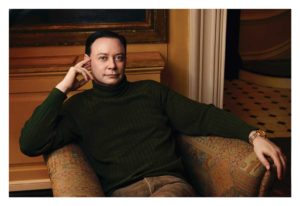

Dee Smith is hardly an alarmist. His erudite, matter-of-fact tone belies the often-frightening subject matter of his recently released documentary series, A World on the Brink. The five-part exploration behind the origins of the world’s current state of unrest is more scholarly than sensational – which makes it all the more terrifying.

At his Camp Bowie West office – Smith, the head of Strategic Insight Group, a private global intelligence company – casually explained the unraveling of the international order.

“Some feel that we may be on the cusp of a large change in sociopolitical organization along the lines of the fall of the Western Roman Empire,” he said. “And it could happen very quickly.”

We are living through a time of historical change. From Brexit to Donald Trump and the rise of extremism and violence around the world, recent political upheaval is threatening the stability of the geopolitical landscape. Throughout the world, there’s a sense of an economic and cultural revolt against globalization from members of an electorate who were seemingly invisible to the political establishment. Populations everywhere are booming while finite resources dwindle. Connectivity through travel, cell phones, and the internet has exposed long-simmering cultural, social, and economic differences and inequalities.

Though the global pivot to the political extremes took many by surprise, A World on the Brink aggregates (as much as five hours of film can) the deep historical roots behind some of the larger, seemingly intractable social and political problems that divide us. Or as Smith puts it in the opening sequence to the series, “We’ve built the most complex society in history, but, increasingly, important parts of it are failing. … It feels like we’re living on the brink, but on the brink of what?”

The series tracks back all the way to the creation of nation states in 1648 and moves forward to the advent of what’s known as the liberal international system and the rules-based international order that has, up until very recently, set the standard for international law, values, and norms. Other episodes deal with globalization, the Middle East, various threats to peace, and what the future might bring. He even offers a few reasons for optimism, such as the declining homicide rate and the spread of the rule of law throughout the world.

Smith’s approach to sussing out the roots of our global ills is deeply analytical. The viewer is confronted with layers of facts, tidbits of little-known but important history, and perspectives from a wide range of more than a dozen experts, including ambassadors, retired military officers, authors, professors, policy consultants, historians, psychologists, and more.

Smith himself draws from more than 20 years of experience in the intelligence world, and his company has operated in 90 countries. He’s been a featured speaker at dozens of forums and other similar events.

He is also informed by a meandering, almost unbelievable career and life path that has seen him conduct symphonies, curate art museum exhibits, broker deals to bring European companies to Latin America, and travel every corner of the world in various pursuits. He comes from a storied Fort Worth family that boasts an envious collection of Native American art and artifacts. If ever there was a Renaissance man among geopolitical policy wonks, it is Smith.

“There’s no plan to my life,” he said. “It’s just, when a door opens in front of me, I usually look inside it and will probably step through it to see what it has to offer.”

A World on the Brink is the culmination of Smith’s varied professional experiences and intellectual pursuits. The series, which premiered in October, is currently available on Real Vision, a subscription-funded finance website that features articles and videos designed to help investors. Real Vision is offering the series to PBS stations nationwide. Broadcast schedules will be announced on pbs.org and will be available on AWorldontheBrink.tv in the coming weeks.

Smith said the timing of his documentaries couldn’t be more urgent. He believes we’re at a nexus point in history.

“It’s possible we could go straight to the edge of the cliff and back away,” he said. “But I could also imagine a scenario in which we go over the edge.”

*****

In September 2016, Smith, as he often does, was speaking at a global security conference, this time in Hong Kong. That’s where he caught the eye of Raoul Pal, the owner and founder of Real Vision, who was filming speakers at the forum. Months later, the filmmaker reached out to Smith about producing a long-form documentary in which he’d be able to delve deep into his subject matter.

“I didn’t know anything about film, and they didn’t know anything about geopolitics,” Smith said. “So it was a perfect match.”

Pal said he was “blown away” by Smith’s insight on private intelligence and globalization. For his website, Pal added, he tries to recruit the “smartest people in their fields.”

Smith, Pal said in an email, “fit that bill perfectly with over three decades of experience in global intelligence and geopolitical analysis. Not only is [Smith] qualified on the topic, he also brought with him an intelligent curiosity to find the real experts and ask the hard questions to investigate what’s really behind the rising chaos in the world.”

After starting pre-production in January 2017, the project took 11 months to complete (it was supposed to take only four), and Smith interviewed 19 people on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. He took home more than 25 hours of footage.

Smith said the process of making the films was an undertaking like nothing he’d ever experienced, but he thought it important to address a few burning questions: Why are we faced with such a sudden escalation of risk, a rapid decline of global order, and increasing social de-cohesion within countries around the world? Why do our presumptions about global order seem to be failing? Why are nationalism, populism, and the rise of illiberal democracy cropping up across the globe? Why has even the West, long seen by many as a bastion of stability, increasingly become a source of risk? Why has a world that seemed relatively stable in the recent past turned such a dark corner toward intensified anger, heightened tribalism, class and ethnic resentment, opposition to immigrants and to globalization, and conflict?

“I see this as a unified phenomenon: Trump, Brexit are symptoms of a deeper change,” he said. “I’m very worried about what’s going on, not just in the United States but globally. I thought the idea of a series provided an opportunity to try and step back, look at the bigger picture, and give a little more nuance than we usually get in our 30-second-soundbite media reality.”

Smith, who speaks with the precision of a Swiss-made watch, as though he’s reading from a teleprompter, said that for his series he wanted to explore three huge, interconnected factors whose interaction has contributed to many of the divisions and much of the turmoil in the world: the astonishingly rapid growth of technology and connectivity, the worldwide population explosion of the last century, and what he calls “legacy human attributes,” which include our innate tribalism and tendency to glamorize the past.

In the 1950s, around 50 million people traveled by air. Compare that to today, when, according to the World Bank, more than 3.6 billion people total are shuttled around the skies globally with relative ease. Those travelers carry with them their own culture, ideas, talents, diseases, and so on. Add that to the more than 7.5 billion cell phones that exist worldwide, plus the rapid growth of internet use in even the most remote areas of the globe, and suddenly the world is connected in a way that didn’t exist even 10 years ago. People are forced to confront other cultures, ideas, inequality, and the streaming mass of humanity that’s been displaced by wars, famine, and the search for a better life.

It took humanity until the early 19th century to gain its first billion people. As of last year, the United Nations estimates, the total world population was 7.6 billion and it is expected to keep growing to 8.6 billion by 2030 – with the outlook for future energy and food supplies looking bleaker than it has for decades. The fight for resources and quality of life are manifesting in ways that no one could have predicted, Smith said.

Throughout history, any period of rapid change has been closely followed by strong sentiments of tribalism, nostalgia, and our tendency to make emotional decisions. These are all the main ingredients to a strange stew Smith calls legacy human attributes. The politics of nostalgia, the idea that if we could just go back to the way things were, Smith said, are a complete fiction.

“It never was the way we remember it, and it never was as good as we remember it,” he said.

When tribalism and nostalgia seep into the collective consciousness, he said, societies are transformed in unpredictable ways as long-held narratives cease to comport with reality.

“All societies have a storyline that gives a rationale for why we live our lives the way we do,” he said. “But times change. And the further and further away we get from the way it’s defined, the more likely it is that one of three things will happen: a transformation, such as the birth of the U.S.; a collapse, like the fall of the Soviet Union; or a snapback, in which we try and wrench reality back to its pre-existing conditions.

“Snapback never works and can’t work,” he said, “so you’re setting yourself up for an even bigger crisis.”

All of these complicated issues that threaten us, Smith said, are of our own creation.

“It’s surprising that you actually can pull out threads and start to make sense of what is going on and why it is happening, particularly if you’re willing to set aside what you think you know,” he said.

*****

With A World on the Brink, Smith takes the unusual approach of tracing the effects of centuries of historical events to make sense of our modern predicament. “In order to understand where we are, we first need to know where we came from,” Smith narrates over footage of him walking into various impressive-looking buildings with his interview subjects.

The series begins by analyzing the creation of the Westphalian Order in 1648, a system that emerged after the Thirty Years’ War wiped out a third of the population of Europe. The system was essentially an agreement among monarchs and leaders that they wouldn’t interfere with the internal affairs of another state. Eventually, those territories became nation states, and that agreement kept the world relatively peaceful for years while creating enduring borders.

The Westphalian idea that a nation’s laws were inviolable maintained generally until the horrors of World War II, when the Allied victory and the advent of the United Nations ushered in the Liberal International Order, a new system designed to ensure such conflicts would never happen again. The biggest problem with that order, the film posits, is that some of today’s modern geopolitical actors never really participated in it.

After the end of the Cold War, the U.S. and its allies developed a political philosophy, and eventually an international law, based on the idea that they had a responsibility to intervene in a sovereign country’s affairs to halt human rights violations. This era of U.S. dominance and the obligation to intervene or “responsibility to protect” has been in sharp decline recently, partly as a result of the two protracted wars with which the U. S. became involved after 9/11.

Globally, doubt crept in as economies everywhere tanked, and a surge of populism and authoritarianism has risen around the world. That all of this occurred at a time of astonishing advances in communication, including social media, only exacerbated mass feelings of uncertainty everywhere.

Noted author Andrew Solomon, a clinical psychology professor at Columbia University Medical Center, said the connection between populism and advancing technology is nothing new.

“Each time there has been a revolution in technologies of communication, a certain amount of chaos has followed,” he says in the series’ opening episode. “After the invention of the printing press came the great religious wars in Europe. After the invention of broadcast media came the dictatorships of Hitler and Stalin. After the development of the internet has come some degree of social decay, because I don’t think we know yet how to interpret or how to control the enormous amount of information we’re now receiving.”

Compounding the fear of new technology is increasing globalization, terrorism, the reemergence of China and Russia as world powers, and many other factors – all of which are reshuffling the deck of the world’s order. That ripple effect has created a toxic political environment in the U.S. and many other countries. People have lost faith in institutions, become increasingly tribal, and some even yearn for the good ol’ days of the Cold War and the kind of familiar power structures first imagined 350 years ago.

Jeremi Suri, a history professor at the University of Texas at Austin who is featured prominently in the series, said that in periods of change, we anchor ourselves to the familiar.

“There’s a common phenomenon of people becoming more religious during periods of transition,” he said in a phone interview. “We crave traditionalism in periods of change, but that often leads us behind the curve in the way we think about who should be leading those periods of change.

“There’s a tendency to look back to a time when America was ‘great’ and hope those great leaders could emerge again,” he continued. “But it’s quite clear now that what we need are new kinds of leaders. And they’re not the ones running for office in most cases. We’ve had three 70-year-olds run for president. In times of change, that makes no sense, unless you understand the emotional motivation of voters and the nature of our party system.”

The collapse of Western power and the rise of non-state actors and the accompanying terrorism in the Middle East are examples of the most pronounced modern resurgence of religion and tribalism. When the Ottoman Empire fell after World War I, the Muslim world was without a caliph, a leader of both political and religious authority, for the first time in almost 1,300 years. In the 1920s, through a little-known treaty, the Sykes-Picot Agreement, England and France carved up the region into arbitrary nations like Syria and Iraq, which had very few common social or cultural traits. Western countries propped up often-corrupt puppet regimes in those manufactured countries, as European allies leached the region’s natural resources.

By the 1930s, groups like the Muslim Brotherhood emerged with an agenda of promoting the importance of Islam. A series of revolutions overthrew many of the artificial monarchies, and new Arab leaders surfaced from the ranks of the military. These strongmen leaders were largely secular, modernizing, and authoritarian.

Resentment toward the West deepened after the creation of Israel in 1947, which led to four regional wars between the Israelis and their neighbors. In 1967, the Israeli military defeated three major Arab states in the Six-Day War. Many Muslims interpreted the humiliating loss as a sign that secularism had failed them. That feeling of antipathy bubbled over in 1979, when the Iranian people revolted and overthrew the shah.

During the waning years of the Cold War, when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, a wealthy Muslim extremist named Osama Bin Laden led a U.S.-backed effort to expel the Russians. Bin Laden became a powerful figure who was deeply upset at what he characterized as corruption in the Saudi royal family. He envisioned ruling the country himself and becoming a new caliphate. When the Saudis asked American-led forces to intervene after Iraq invaded Kuwait in the early ’90s, that set the stage for the decades of terrorism that followed.

Roderick Grierson, the director of the Rumi Institute at Near East University in Nicosia, Cyprus, who appears in every episode of the series, said the collapse of the Ottoman Empire offers a harsh lesson in history for every empire.

“The most obvious lesson is that our day in the sun will not last forever,” he said in an email. “This is not pessimism. It is no more pessimistic than noticing that autumn and then winter follow summer.”

*****

One entire wall of Smith’s Westside home is covered in authentic Latin American folk masks of varying degrees of elaborate detail, all of which he bought on various trips south of the border. On the adjacent wall are shelves stocked with books ranging in topics from metaphysics and Eastern philosophy to physics and string theory. His office is adorned with artifacts and art from around the world: old maps, statues, and prints. It’s not that he wears his worldly intellectualism like a badge. It’s just who he is.

His peripatetic nature and love for art were passed down from his parents and grandparents, he said. Smith’s father, Gordon William Smith, amassed a major collection of Native American art, most of which is housed at the Houston Museum of Natural Science.

When Gordon was 5 years old, he met a Native American named Two Guns White Calf, the Blackfoot Indian who posed for the Indian-head nickel. The old chief gave Smith’s father a rattle that’s still in his collection in Houston. That was the start of a pathway throughout his entire childhood that led to his obsession over American Plains Indian culture. Gordon was inducted into the Oglala Sioux tribe as a teenager and given an Indian name, which translates to High Bear. Gordon grew up to be an artist but maintained his interest in Native American culture to his death in 2010.

“He had an intense relationship with Indians,” Dee Smith said. “As a child, he knew a lot of old Indians who had fought the white man and were then in their 80s and 90s. And at that time, some of their children were not as interested in Indian culture. So they were stunned with this little boy from Texas who was just fascinated with it and knew so much about it. … It became part of who he was.”

Smith grew up in a household full of shamanistic objects of Indian culture and Western art from around the world. His mother was an early pioneer in the television industry and a host of a talk show on the local NBC affiliate called The Ann Alden Show. She was also a longtime board member of the Van Cliburn Foundation, and Cliburn was a close family friend. Smith’s grandfather, W. D. Smith, was one of the founders of the Cantey Hanger law firm.

Smith’s wanderlust was inherited from his grandmother, a trained opera singer, with whom he would travel every summer.

“She was a little ornery, I guess, a little difficult to get along with for most people – not me – and really nobody else wanted to travel with her,” he said. “So by the time I was 13 or 14, I’d been all over the world.”

Smith’s first academic pursuit was music. Starting at age 11, he studied music theory with noted composer Ralph Guenther, then TCU’s head of music theory. By the time Smith was 15, Guenther convinced him he was ready to study music at the collegiate level, so Smith skipped the last three years of high school and enrolled at TCU, where he eventually earned his degree.

“And I think it was really a mistake to do that,” he said about leaving high school early. “When you’re 18 or 20, who wants to have anything to do with a 15-year-old kid? It was socially awkward. It wasn’t as fun as it should have been.”

Smith went on to conduct for several TCU orchestras and the Fort Worth Youth Orchestra and in cities such as New Orleans, the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, and others.

Few people have legitimate career changes at age 20, but Smith decided music was too demanding of a mistress and decided to pursue other passions, such as archeology.

During a chance trip to Mexico to visit Maya ruins, he passed a billboard advertising a workshop at UT led by well-known Meso-American scholar Linda Schele. The ad claimed that she had decoded Maya hieroglyphics, which was previously thought impossible.

After attending the workshop, he was so impressed by her findings, he asked if she’d be interested in taking this new scholarship, producing an exhibit on the ancient Maya, and retelling the story. Schele agreed but only if Smith could give a more complete picture of the Maya hieroglyphics, which involved convincing the British Museum to loan out three stone-carved lentils from about the Eighth century. Ted Pillsbury, former curator of the Kimbell Art Museum, agreed to show the exhibit in Fort Worth but on the same condition.

After a few tries, Smith finally contacted the Keeper of Mesoamerican Antiquities of the British Museum, who invited him to London to meet at the museum’s storehouse.

“It’s one of the strangest places I’ve ever been,” Smith said. “It was very dark, with only slit widows at the top. She handed me a flashlight, and said, ‘You’ll need this.’

“We went in, and the whole world was there,” he continued. “You’d turn a corner, and here were 15 Egyptian statues. Another and here were a whole shelf of New Guinea carvings. There was a huge collection of Amazonian featherwork. … It was a scene out of Indiana Jones.”

The museum agreed to loan the artifacts to him, and that landmark exhibit completely changed the established scholarly opinion about the Maya. The show also launched Smith’s second career as an art museum exhibition curator. At the same time he was developing the Maya exhibit, he, along with a few friends, created a non-governmental organization called InterCultura. For 10 years, the group organized shows all over the world and facilitated cultural exchanges with post-Soviet Russia, Ethiopia, Japan, and Mexico, among many others.

“The idea was to send American art abroad and bring art from other countries to the U.S.,” Smith said. “We sent a Robert Motherwell show and a Georgia O’Keeffe show to Mexico, and so on.”

Throughout that 10-year period, Smith learned how to negotiate with foreign ministries and worked closely with different U.S. embassies and the U.S. State Department. Those connections and experiences led to a short career as a venture capitalist that, under the aegis of his company Cima International, connected European investors to Latin America companies. When the value of the peso plummeted in the mid ’90s, a friend who worked in intelligence suggested that Smith use his analytical, research-oriented brain and wealth of foreign contacts to create a private intelligence company.

“When I had been doing these venture capital deals, there was always a lot of information I wanted and needed, and the only way to get it was to do it myself,” he said. “There was no one to go to for the kind of insight I needed. So that made me think, ‘If I as an investor needed that, then other people will need it.’ So putting all of that together, I formed this company.

“The best passive information is still on proprietary databases,” he continued. “It’s not on the internet, but a lot of the information investors need has to be gathered from ‘close-source’ agents on the ground and from high-level sources and painstakingly put together, which is where working with people all over the world for many decades comes in very handy.”

*****

One of the repeated lessons that A World on the Brink teaches is the danger of politicians and voters who make reactionary decisions based on immediate political or economic returns. From 1960 to 1990, the middle and lower-middle class workforce of the United States experienced unprecedented – and, now we know, unsustainable – growth and prosperity. Our leaders and many observers assumed the good times would last indefinitely. We, convinced of our own ascendancy, began to focus on short-term gains instead of looking forward. Gains in the last 30 years have focused disproportionately on higher-earning, wealthier segments of society, resulting in many other people feeling — and indeed, being — left behind. This has resulted in wealth disparity that is fracturing society.

“The disparity between the 90 percent and the 10 percent is at least as concerning as between the 99 percent and the 1 percent,” Smith said.

As the ill effects of our shortsightedness have begun to manifest themselves, our political system has become more divided than ever. Or as Smith says in the series’ final episode, “Just as our conditions are becoming more fluid and unpredictable, our attitudes are becoming more rigid and unyielding.”

Grierson suggested that we’ve entered a new age of modern identity politics that’s more dependent on what you believe rather than sharing a cultural or familial connection. That kind of loyalty, he added, is only temporary.

“Those who simply disagree with us are now denounced as enemies, it seems, or as traitors,” he said. “We should think very carefully before we believe this, especially if there are real enemies in the world whom we are choosing to ignore.”

In our fast-moving social media age, when the speed of the news cycle can distort our understanding of the day’s major events, it’s easy to look for simple answers, Suri said.

“What social media does is that it confronts us with unending images and information,” he said. “Just the very disorientation that creates leaves us feeling that we’re out of control and that we need a simple answer to a lot of complex problems. It’s an information overload problem.

“I see this with my students all of the time,” he continued. “They don’t agree with anyone, but they don’t know where to start. They just throw up their hands and say, ‘I know too much. I don’t know where to start.’ ”

He added that the younger generation offers hope for our political future, that, for now, they are yearning to support centrist politicians and defy labels like “Democrat” or “Republican.”

“They see problems in our world, and they want to solve them,” he said. “That problem-solving is going to find its way more than ever into our politics, and that’s going to make us much better.

“I actually think if we can get through the next few years, we’re going to be a better country,” he said.

At the end of his series, Smith suggests that our past may not offer all of the answers we need for our future and that maybe it’s time for something new. He adds the caveat that we must also overcome our nostalgia and perceptions, find a way to work together, and more willingly accept change.

“My concern is that we are so focused on events and proximate causes that we are not looking for the ultimate causes,” Smith told me. “But unless we understand those, we have little hope of finding solutions to any of this.”