The couple hundred fans who had gathered around the entranceway to Cinemark West Plano let out a roar as he arrived. I didn’t see this. I heard it from inside the theater while clustered with nearly a dozen entertainment reporters from across North Texas. Metal barricades had been placed alongside the red carpet for us. I stood next to the barrier, camera around my neck, digital recorder in hand. A publicity official had instructed me to stand near a white piece of paper taped to the floor with “Fort Worth Weekly” written on it. I squeezed in near CW33 TV reporter Shardae Neal and Kidd Kraddick Morning Show radio correspondent Part-Time Justin.

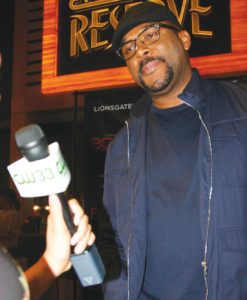

There for the premiere of Boo 2! A Madea Halloween, Tyler Perry entered the building after saying goodbye to the fans outside. He began stopping in front of each reporter to pose for photos, answer a few questions, and then move to the next media member in line. The director/writer/actor is a big, charismatic guy standing about 6 feet 6 inches tall and looking fit and handsome. He was accommodating and slipped into an easy-going banter during the interviews. How does it feel to be in Dallas? (Great.) Where do you like to eat in town? (Pappadeaux Seafood Kitchen.) What kind of candy do you give out on Halloween? (None. His house is set back too far from the road.) Can you do a Madea impression for our viewers? (You bet.)

When Perry reached me, I asked about his theater history in Dallas. He described how from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s he had performed plays at the “Black Academy Theater,” established as The Black Academy of Arts and Letters 40 years ago at the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center.

Then I swallowed hard and did what I had come to do.

“Why have so many writers over the years accused you of plagiarism?”

Perry glanced at his publicist with a look that spoke something along the lines of, I pay you to keep jerks like this away from me.

The movie mogul looked at me and said, “I don’t even know where that would have come from.”

“From the number of lawsuits that have been filed,” I said, referring to at least five litigants who have accused him of copyright infringement over the past decade (and lost) and some who have banded together to accuse him (so far unsuccessfully) of violating the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. It’s currently on appeal.

“The number of lawsuits where not one person ever won?” Perry replied, his voice rising slightly and the tempo of his speech increasing. “Where not one was ever settled? And every one of them was very clear that I have written everything myself?”

Perry’s smooth visage had been momentarily jarred, his speech rambling.

“Here’s the thing about that,” he said. “When you tell common stories, I think people believe that what you’re telling them is what they’re saying, everybody knows. So if I’ve got a story, if I tell a story about a woman who’s mad and you tell a story about a woman who’s mad, it’s not the same story.”

I asked if he was referring to Tyler Perry’s Diary of a Mad Black Woman (2005) – his first movie – and Fantasy of a Black Woman, a play written and performed by Fort Worth’s Donna West that premiered at the Black Academy theater in the summer of 1991.

“I’m not talking about anything else with you,” Perry told me.

He moved farther down the red carpet, giving more interviews. Not far away, security and theater personnel kept back a crowd of onlookers trying to breach the barricade. A short African-American woman with a resolute look was ignoring them as they politely suggested she move back. It was Donna West. She planted her feet near the end of the red carpet where Perry was slowly heading, and she wasn’t budging.

She had waited years to confront Perry face to face.

That moment was about to come.

*****

West is a mad black woman – perhaps the original mad black woman. She isn’t mad 24/7, of course. Most of the time she is gracious, poised, and well-spoken. She grew up poor in Fort Worth, married early, and lived with a man she describes as a verbally and physically abusive husband. They divorced in 1984. She raised their three children as a single mother, with each dramatic turn of her life making her more resilient, she said, before marrying her second husband, Doug, in 1996.

After West became convinced that Perry had made a movie out of the play she had written 15 years earlier, she was ready to fight for what she believed was hers. She wanted writing credit and a cut of the profits. Released in 2005, Perry’s film Diary of a Mad Black Woman – made on the cheap – earned an estimated $50 million in the United States.

Perry was already a successful theater darling in Atlanta when he ventured into filmmaking. He had staged a successful theatrical version of Diary of a Mad Black Woman in 2001, taped the performance, and sold DVD copies on his website. He used the same project to launch him into the Hollywood stratosphere a few years later. The film version of the play helped him establish an entertainment empire and compile personal assets currently estimated at $600 million, according to Celebrity Net Wealth.

White moviegoers might not be as familiar with Perry’s movies, which are generally directed at black audiences, but he is a box office powerhouse with many of his films opening at No. 1 over the years. Just about every Perry movie after Mad Black Woman has performed in similar fashion. The movies are funny at times but mostly painfully bad, clichéd, and stereotypical for the most part yet popular. And profitable.

In 2007, West filed a lawsuit accusing Perry and the company that distributes his films, Lions Gate Entertainment Corp., of copyright infringement.

West received a $200,000 settlement offer from Lionsgate, she said, providing me with a copy of an emailed settlement offer from a company attorney as proof.

West refused the offer. The words she had typed on paper while writing her play were more than creative expressions, she said. She poured her spirit into writing and staging Fantasy of a Black Woman in response to being ditched and humiliated by her ex-husband. Writing gave her a way to exorcise demons while attempting to generate money to help feed her family. Having another man – Perry – come along, apparently revamp her play, earn millions from it, and cut her out of any payoff made her feel as if she had been abused again, she said.

She felt certain jurors would side with her.

They didn’t.

In December 2008, the jury in a federal courtroom in the small East Texas town of Marshall voted unanimously in favor of Perry. After the trial, the jury foreman described the proceedings to Associated Content as “confusing and fascinating.” He said the storylines were “very similar.”

More recently, the jury foreman, Steven Cotterman, told me that nobody during the trial – neither the attorneys nor the judge – defined copyright infringement for jurors, leaving some of them uncertain when determining the verdict. The court of appeals, however, determined there was no error in the jury charge.

The following year, West sought a new trial, claiming, among other things, that one of Perry’s witnesses wasn’t qualified to testify. But a U.S. district judge dismissed her claims, and, in 2010, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld that ruling.

I called Perry’s studio, asked to interview him, and left a message. A member of his publicity team spoke with me several times over a period of weeks and said she wasn’t interested in letting Perry speak to me about alleged copyright infringement cases that didn’t hold up in court. She asked that our conversations remain confidential.

The $200,000 settlement had been offered by a Lionsgate attorney. The Los Angeles-based Louis Petrich did not respond to my calls for comment. His online resume lists him as the trial and appellate attorney for Lionsgate in “obtaining a defense jury verdict … on copyright infringement case against [the] movie Diary of a Mad Black Woman.”

Perry was born in 1969, grew up in New Orleans, and has been outspoken about his tough upbringing with an abusive father. Perry began writing as a teenager and has described being poor and even living in his car before staging a successful play in 1998 and branching into TV and film. By 2016, he had several TV shows airing on OWN, Oprah Winfrey’s TV network, and said he wrote every episode himself.

“I don’t have a writers’ room,” he told ABC News in 2016. “I write all the shows myself. Ninety-one episodes a season, I’m sitting there at the computer writing, and writing, and writing because I want the voice to be authentic so that the audience is hearing from me and not other writers.”

Perry appears intent on crediting himself. His name appears 26 times in the opening and closing credits of Diary of a Mad Black Woman.

Prior to moving to OWN in 2012, Perry’s Tyler Perry’s House of Payne ran from 2006 to 2012 and his Meet the Browns series ran concurrently from 2009 to 2011, both on TBS. He published a book in 2006 and another more recently. Add to that at least 18 movies of his that were written and made between 2005 and 2017, and about 20 plays, and you have one busy writer.

*****

West was disappointed and frazzled when her loss became final with the appellate court’s decision in 2010. And life kept coming. She dealt with health problems, the incarceration of a child, her second husband Doug’s death, and other calamities. She helped raise her grandchildren. Years passed. But West never forgot about her play.

“It’s like somebody stealing your baby,” she said. “You don’t get over it. It was very personal to me.”

A few months ago, West decided to sort through the trial and deposition transcripts that she had stored for almost a decade inside cardboard boxes at her house.

“It has taken me this long to even open up the depositions, the paperwork, all of this stuff,” she said. “I’m finally in the state of mind to do that.”

West searched online to track down other cases involving Perry and discovered several other lawsuits alleging copyright infringement.

Among the other writers who have sued Perry is Terri Strickland (formerly Donald), who accused him of stealing from her 2007 novel Bad Apples Can Be Good Fruit to create his movie Good Deeds (2012). The following year, William James claimed Perry had based Temptation (2013) on James’ 2011 screenplay Lovers Kill. Like other writers before them, Strickland and James lost their claims in court and received no credit or financial compensation from Perry.

James told me that he considers Perry a “menace to society.”

Strickland and James have begun compiling a master list of other authors claiming to have been ripped off by Perry over the years. So far, they claim to have tracked down 18 others. Strickland and James considered filing a class-action copyright infringement lawsuit but later changed their minds, characterizing those laws as toothless. Strickland and James are currently pursuing the RICO lawsuit, which has already been dismissed and is now on appeal.

They accuse Lionsgate, Perry, his longtime business associate Oprah Winfrey, and OWN of conspiring to steal other writers’ material to feed their production machines.

“They go after average hard-working people who will never be able to deal with the litigation issues, the finances, the time to invest in the legal argument,” Strickland said.

Perry is the first black filmmaker to own a major film and TV studio. Strickland said she sent copies of her book to Winfrey’s book club and to Perry’s production company in 2008. Perry’s movie that Strickland claims is similar came out a few years later. Strickland said Perry changed his movie enough to avoid being successfully sued.

Perry, she said, is a “conniving individual. He claims to be this triple threat and does all the work himself.”

The judge hearing Strickland’s lawsuit wrote that copyright law “only protects expression and not ideas, and that the only similarity between the two works was that they both concerned a romance between a wealthy black man and a woman who was experiencing hardship.”

The film blog IndieWire quoted an attorney for Perry as saying that plaintiffs had been “crawling out of the woodwork” to go after his client and that “everyone thinks if they have an idea and there is something else like it, it must be copyright infringement.”

The author of the IndieWire article, filmmaker Tambay Obenson, said that verdicts “will likely almost always be ruled in favor of the defendants, who probably have highly paid and skilled lawyers who know how to manipulate the system on their client’s behalf.”

I had read news reports about a North Carolina songwriter who had sued Perry in 2010. Johnny Tyrone Stringfield claimed the music and lyrics of one of his gospel songs were used by Perry on Meet the Browns in 2009. Stringfield sued for copyright infringement, seeking $100,000. The case was settled out of court.

I messaged Stringfield on social media and asked for an interview.

“Hi, this is nothing to damage [Perry] is it?” he responded. “We don’t want to hurt him. He did a good thing for us.”

Later, in a phone conversation, Stringfield said, “We pretty much settled out of court, and they put a confidentiality clause on it. That’s pretty much where I stand.”

In 2009, the estate of Bertha James made a similar infringement claim against Perry, who allegedly incorporated lyrics from the James-penned “When I Think of the Goodness of Jesus” into the 2009 film Madea Goes to Jail without permission. The case was dismissed without a motion.

West’s legal avenues might be closed, but she figures the court of public opinion remains wide open. She believes social media can provide her with a new platform to air her grievances. Recently, she created a YouTube video in which she summarizes her complaints against Perry and announces the creation of a crowdfunding page. She wants to raise enough money to produce a documentary that she hopes will draw attention to Perry’s filmmaking and writing techniques.

In the video, she holds onto her belief that Perry’s movie is based on her play: “I’m the original writer of Diary of a Mad Black Woman – yes, the one that Tyler Perry claims to have written.”

The mad black woman’s focus and energy have returned.

“The truth will be told,” she says.

*****

West introduced herself to me for the first time several years ago after stopping by the Weekly office to try to convince someone to write a story about one of her daughters, who West said was wrongly incarcerated. West, husband Doug, and several others had been picketing outside Tarrant County Jail. I agreed to look into the matter and spent many hours digging into the case before deciding against writing a story.

Recently, West called again, this time with a new story to pitch: A wealthy Hollywood icon had allegedly stolen her play.

I could not have been more skeptical or less interested.

In between yawns I tried to shoot holes in her story. West kept countering with information that made me go, “Hmmm.” The part that intrigued me most was her turning down a $200,000 settlement offer. I agreed to look at her documentation, and she came to my office loaded with stacks of trial transcripts, depositions, scripts, and trial evidence.

West was born in 1956 in Fort Worth and has lived here ever since. The fourth of nine children, she sang in church while growing up. She dropped out of Trimble Tech High School in 1975 after getting married but earned her GED several years later while raising her kids. Around that time, she saw a play at the Black Academy in Dallas and was floored by the artistry and magic that transported her away.

“It was an inspiration,” she said. “I was intrigued.”

She was performing gospel music in churches around North Texas and decided to launch a career as a singer. She self-financed a gospel album at a local recording studio and sold 3,500 cassettes out of the trunk of her car in two weeks, she said. She was pegged to tour and open for Walter Hawkins, formerly of the Edwin Hawkins Singers, a group made famous by their rendition years earlier of “Oh, Happy Day.”

“While we were on tour … I began to have severe headaches,” West said.

Unable to perform, she returned to Fort Worth and learned she had a benign brain tumor, she said. She took medication for years to control the growth of the tumor, which was later shrunk through electromagnetic wave treatments, she said.

“I decided to write because at the time I didn’t know whether or not I would be able to raise my kids,” she said. “That started my journey.”

She wrote about her marriage, divorce, feelings of inadequacy, religious faith, and willingness, at least for a while, to swallow her pride and continue clinging to a man who treated her poorly.

“I called it Fantasy of a Black Woman,” she said. “The fantasy was finding someone who was sincere and committed to a marriage and relationship.”

She envisioned a cast of actors portraying her story while she would appear onstage periodically to sing. She had heard about a producer named Curtis King who leased space at the Kay Bailey Hutchison center to people wanting to stage shows.

“Before I could put the show on, Curtis King said he had to have a copy of the script,” West said. “He said he didn’t want any junk in the theater. I gave him a copy of the script.”

West said she had received $10,000 from Arthur Rose, an investor who believed in her play and offered to help fund its production.

Photo courtesy Donna West.

“I had a full cast,” she said. “I directed it myself. It was my first time out of the chute, my first play, but it went pretty good.”

She sold tickets through Ticketmaster, drew about 600 people over three days, and earned about $8,500, she said.

She wanted to write and produce more plays, but she and King had a falling out soon after, she said. West said King had charged her $1,500 to pay for ushers who, she thought, had volunteered to work for free. She confronted King.

“He got angry with me and blackballed me from the auditorium from that day forward,” she said.

King, who still oversees the Black Academy, did not respond to my interview request for this article.

In addition to the Dallas shows, West wanted to stage her play on a national tour or maybe even make a movie. She sent her script to Winfrey and Montel Williams to seek financing and received form letters from both saying, in effect, don’t call us, we’ll call you.

In 2006, one of West’s children described seeing a movie that was comparable to Fantasy of a Black Woman.

“I got a copy of the DVD and looked at it,” West said. “I’m bursting in tears because I knew that was my work from the moment it opened up.”

She noted similar scenes, plot devices, characters, and occasional snippets of dialogue, not to mention the titles.

“The name of it got me – Diary of a Mad Black Woman,” she said. “Fantasy of a Black Woman. That’s too close for comfort.”

Also, Perry’s title sounds similar to Diary of a Mad Housewife, a 1970 film.

West began cataloguing comparisons to Perry’s play and movie. I have verified most of them. The works involve homemakers experiencing spiritual and marital crises just prior to their wedding anniversaries. The women try unsuccessfully to entice their husbands by wearing sexy gowns. The husbands confess they are leaving their wives for younger women and flaunt the women in front of the wives. The husbands are depicted as abusive adulterers and are accused of being quick on the trigger in bed. The women visit their mothers and give them gifts. The mothers preach about inner strength and take their daughters to church. The men experience paralysis. The women find strength in their religious faith and ultimately reject their spouses’ attempts to reunite. The projects feature religious music and themes.

To test her theory that her play had been used, West said she called the theater department at a local college.

“I started searching for a professional to look at it and tell me whether or not it was the same work,” West said. “Not just my opinion. I wanted a professional. I just randomly chose a school.”

Texas Wesleyan University theater professor Connie Whitt-Lambert agreed to read West’s play. She watched Perry’s version of the play on video.

Whitt-Lambert “said it was a variation of the same work,” West said.

I asked West why Whitt-Lambert viewed Perry’s version of the play rather than the actual movie. West said Perry’s play was more similar to Fantasy of a Black Woman than his movie, but she believed both were very similar to her original work.

Whitt-Lambert wrote a short letter on TWU letterhead dated April 12, 2006, that said in part, “I have read your script Fantasy of a Black Woman and watched the DVD of Diary of a Mad Black Woman, The Play,” she wrote. “I have also studied your comparison sheet and can understand your belief that Tyler Perry’s work may have been based on your own. The general plot is unusually similar to your script, and several incidents seem to mimic those in your play.”

The spurned women in both works seem “unusually alike,” Whitt-Lambert wrote.

She ended the letter by writing, “To state it briefly, Fantasy of a Black Woman and Diary of a Mad Black Woman seem to be variations of the same play.”

I called Whitt-Lambert at TWU to corroborate her statements, but she did not return my call. Later, she emailed me saying she did not wish to be interviewed for this story. She offered no details regarding her silence.

The professor’s letter had emboldened West, who contacted Dallas attorney Aubrey “Nick” Pittman a short time later.

“Mr. Pittman reviewed everything and did the side-by-side comparison,” West said.

The similarities between West’s play and Perry’s movie seemed to be obvious to the attorney, she said. But there were major differences as well. West’s play is dramatic. Perry’s is more comedic. And the popular Madea character, in which Perry portrays a sassy older woman, appears in his movie only.

(A few years ago, a drag queen comedian who performed in Atlanta gay clubs under the name Miss Sophia publicly accused Perry of basing the Madea character on Sophia and stealing jokes and other stage material and putting them in his movies.)

While watching Perry’s Diary movie, I noticed a general lack of originality and a tendency to borrow from other works. For instance, Madea becomes enraged after seeing a wire hangar in a closet, a take-off on Mommie Dearest (1981). In a courtroom scene, Whitney Houston is heard screaming “Bobbbyyyy!,” a reference to her bellowing her husband’s name in Being Bobby Brown (2005). In another scene, a woman smokes a joint, gets high, and thinks she’s gone blind until someone tells her to open her eyes. I’ve seen that gag before, probably on The Three Stooges or a bad Cheech and Chong movie.

*****

West had no money to speak of, but Pittman agreed to represent her on contingency. They filed her original lawsuit in 2007. Perry responded by denying copyright infringement.

In West’s suit, she claimed that she hand-delivered copies of her script to several people in 1991 while seeking support and financial backing. In the years to come, some of those people who received a script appeared to West to have direct ties to Perry.

The Black Academy’s King was deposed prior to the trial but denied knowledge of West’s script.

West said she also gave a copy of the script to Tamela Mann, a local actress and gospel singer, who would later appear in Perry’s stage and movie versions of Diary and other projects. West said she and Mann performed on the same gospel circuit and knew each other but were not close. She had hoped Mann could deliver the script to somebody who might help West in staging the play.

Under questioning in court, however, Mann denied knowing West.

The trial in Marshall lasted the better part of a week. The Marshall News Messenger quoted a consultant saying that West should receive about $40 million in damages if the judge ruled in her favor.

“Tyler Perry got up there on the stand, and all of a sudden you thought the water hose was turned on,” West said. “He wet up his whole clothes just crying like a baby. He said, ‘Ms. West, you know I would never steal nothing from you.’ I’d never even seen him before in my life.”

West gave me the name and number of a Dallas businessman who had testified on her behalf during the trial. L.D. Dabney, now retired, told me that he had been friends with Doug West, who had given him a copy of Donna’s script after it had been staged in Dallas. Years later, Dabney was hanging out at a friend’s house and noticed a DVD playing with a plot that seemed awfully familiar.

“I said, ‘Oh, that’s Donna West’s play,’ ” Dabney recalled.

He called Doug West to congratulate him on getting the play turned into a movie. Doug told him they weren’t involved in making the movie. Dabney offered to testify that he had read West’s script long before Perry’s play or movie had been made.

“If that trial had been done in Dallas, [West] would have won,” Dabney said. “That was an all-white jury, and Tyler Perry got up and started crying and crap. The way he approached that audience, that jury, it was like [West] was trying to steal from him. They bought into that.”

I asked Dabney why the color of the jurors mattered since the plaintiff and defendant were both black.

“If black people were on that jury, there is no way Perry could have pulled that off,” he said. “They know game when they hear it. And that was game. You understand? He started crying and saying every time a black man gets successful, another black person comes and tries to steal their money. That will work in Marshall, Texas, but that won’t work in Dallas.”

Dabney suspected Perry’s celebrity might have wooed the jury.

“You go with the guy you kind of know, and Tyler Perry was who they knew,” he continued. “Here comes a woman out of the blue saying a famous guy stole her stuff. When I left court and came back to Dallas, I thought she was going to win. She had done her job well enough for those people to believe that something wasn’t right.”

Jury foreman Cotterman, however, said few jurors knew who Perry was or cared, especially after watching his movie in court.

“I wasn’t impressed by him at all,” Cotterman said. “I wouldn’t pay $2 to see it at a movie house.”

Likewise, he described West’s play as “thin.”

All these years later, Dabney hasn’t changed his mind.

“I think Tyler Perry read that play, [used] what he thought was great, and is weak for not giving that woman something,” he said.

Our conversation, however, revealed something else. Dabney told me that Doug, West’s second husband, had asked him for $10,000 in the early 1990s to help the Wests stage their play in other cities after the Dallas performance. All these years later, I asked West whether she had ever re-staged her play. She said she hadn’t. I asked what happened to the $10,000 investment from Dabney. West said she didn’t know anything about it. Days later, we discussed that money again. West was learning to live with the uncomfortable possibility that Doug, who died several years ago, might have kept the money without telling her.

Copyright law is complicated, but in general it gives authors of original material the sole right to publish and sell their work. Copyright infringement occurs when someone reproduces, distributes, or performs a work without permission of the copyright owner. However, copyright law provides leeway to people who create something similar but not exactly like an original work.

Avatar, Cars, Finding Nemo, The Matrix, Ted, and Titanic are just a handful of the many movies whose creators have been unsuccessfully sued for copyright infringement. Other cases have been settled out of court, such as when The Walt Disney Company settled with a woman who claimed the trailer for Frozen copied her short film.

Jury foreman Cotterman admitted that he was perplexed while the jury debated the case against Perry.

“I didn’t understand the law, and nobody would explain it,” he said. “I didn’t know what copyright was. I didn’t know when copyright occurs. Just because you write something, is it copyrighted? I don’t know. I still don’t know to this day.”

The attorneys for both sides were vague, he said.

“They would have been better off if they would have discussed the nuances of the law,” he said. “What does plagiarism entail? Is it just the idea? Actual words? Chunks of action? We weren’t really sure. I was waiting the whole time for somebody to say this is the law and this is what you should be ruling on. They never said a word. Not even the judge.”

During the trial, West’s attorney presented a copy of The Texas Times, a now-defunct Dallas newspaper geared toward the African-American community. The July 11, 1991 edition featured an article under the headline “Fort Worth Author’s Play Opens in Dallas” and announced the run of Fantasy of a Black Woman, July 19 to 21. But the paper was written prior to the play’s presentation. A review of the play did not appear afterward. Perry’s attorney noted that West was unable to present reviews, playbills, or video images to prove that the play had been performed.

Through the days of testimony, Cotterman sat, listened, and became more confused.

Cotterman said the verdict could have gone either way but that most of the jurors sided with Perry from the start. Even if West had given her script to people with ties to Perry, that didn’t prove that he saw it. And the things that Perry appeared to have borrowed from West’s play amounted to basic plot devices rather than specific dialogue.

“What is it they used to say in college: ‘There are only [seven] different plots in the entire world?’ ” he said. “You’ve got to be a lot more similar than that.”

The jury spent an hour debating the case before voting 12-0 in favor of Perry.

As for West, Cotterman said, “If she can get a documentary and get some money out of it, maybe she’ll be happy.”

I’m no expert on copyright infringement. I’ve read West’s play and watched Perry’s movie. It seems unlikely that Perry could have written his work without seeing West’s play. There appear to be similar details in characters, scenes, and settings. But Perry’s premise has plenty of differences, including varying characters and subplots.

If I saw a new movie about a guy who wanted to kill himself to collect insurance money to give to his family right around Christmastime, I would think, “They borrowed that plotline from It’s a Wonderful Life.” Would the new movie be legally bound to pay for that alleged copyright infringement? Not unless the dialogue was the same.

What if the new movie featured a young girl saying, “Every time a bell rings, an angel gets his wings?” I would be curious to know if that phrase had ever appeared in print or film prior to A Wonderful Life’s release. It doesn’t seem like you should be able to copyright a cliché. But if that line first appeared in A Wonderful Life, then using it in a subsequent film might constitute copyright infringement.

If I had been on the jury of West’s lawsuit, I might have voted for Perry as well. The basic plots and titles are similar, but, from my understanding of the law, basic plots and titles aren’t protected. Perry’s movie seemed amateurish but so did West’s script. The few lines of dialogue that West claimed were stolen from her play are well-worn phrases that hardly qualify as original.

Like the head juror and the theater professor, I felt a similar sense that Perry might have appropriated some of West’s work but not to the extent that he would be legally liable.

*****

Crowdfunding efforts haven’t gone well for West. Her YouTube video posted on May 30 has been seen 1,650 times and liked by 104 viewers, but it has prompted no contributions. West plans to redo the video, making her request more clear and concise and providing a more noticeable link to her crowdfunding page.

She doesn’t get discouraged easily.

On a recent afternoon, I told West that Perry was making a red-carpet appearance in Plano that evening. Immediately, West said she wanted to attend, even though she hadn’t been invited. Perry’s publicity team had sent the invitation to the Weekly’s film critic. I intercepted it.

I tried to beg off, telling West that Perry’s PR team had made it clear that he wasn’t interested in discussing her lawsuit. Questioning him about it on the red carpet would be tacky, I said. West persisted. She and other unknown writers feel ripped off by this guy, she said. He’s too rich to compete with in court, she said. Isn’t it a reporter’s job to dig hard and confront people for answers? I compromised.

“If you are willing to drive to Plano in the slight chance that you’ll get to confront Tyler Perry in person, I’ll meet you there and document it,” I said.

Three hours and one long traffic jam later, I arrived at the cinema late and saw West waiting outside with one of her grandchildren in tow. She had dressed herself immaculately and was wearing pretty but uncomfortable looking shoes. Perry, too, was running late but arrived shortly afterward.

I stood in line with the other reporters while West anchored herself at the end of the red carpet in an unauthorized area.

She watched as Perry cut his interview short with me. Watched him continue down the line. And, just as he finished with his last interview and headed toward the theater where his movie was premiering, West made her move.

“Tyler Perry!” she hollered from behind the barricade.

Perry looked her way, smiled, and approached her. Nine years had passed since they had seen each other. Perry looked her in the eye and extended his hand. West shook his hand and was shocked to hear Perry call her by name.

“Donna West, how are you doing?” he said.

“Fine, we need to talk,” West replied.

“Oh, no,” Perry said, pulling his hand back quickly before disappearing into the theater.

Few words had passed between them. Little appeared to have been accomplished. I figured West might have been disappointed.

She was thrilled.

During the trial, West hadn’t been able to talk to Perry directly, she said. He entered and exited the courthouse at different times than she did. Looking Perry in the eye at long last and letting him know that she wasn’t going away had meant the world to her, she said.

“I was at peace,” she said. “It was the first time I got to confront him. I felt like I was accomplishing something. He realized the chickens are coming home to roost.”

After reading this article, I asked myself ” Why would someone knowing the truth will deny a poor woman her dues? Is it that people don’t fear God anymore? My prayers are with her and millions like me that have been knocked down due to lack of money to fight for justice. God will surely fight for her and she will get her justice this year in Jesus mighty name amen.

Amen! I pray West receives everything she is due. I have had several encounters with Perry. He is not at all who people believe he is.

I speak The Luke 12:2-3 Word of God over Donna West and May My God GET THE GLORY!!!

For there is nothing covered, that shall not be revealed; neither hid, that shall not be known. Therefore whatsoever ye have spoken in darkness shall be heard in the light; and that which ye have spoken in the ear in closets shall be proclaimed upon the housetops.

Luke 12:2-3 KJV

Amen!

I just saw Perry ministering at Lakewood church with Joel Osteen. He “appears” to have a caring heart, and since his net worth has increased and he wouldn’t even miss it… perhaps Perry will at least let Ms. West appear in one or two of his movies, so she can receive some monetary compensation. If he were to pay her publicly, it would just open the door to many other skeletons in the closet.

A lesson learned is that, it’s ok to be excited about your dreams and accomplishments, but be sure to your dudilligence, form a board of advisors, and make sure you have your s#!t together and your ducks in a row before trusting anybody with your ideas.

Lastly is BIG… Make your own money so you don’t have to ask anyone for theirs.

I’ve Been there…and done that!

I shared an Idea with a mega church pastor, the pastor immediately shared it with his family member, who produced my very unique idea in a matter of a few months before my very eyes.

Yes! I was betrayed, but learned a lesson very quickly. I offered that up to God. I forgave that person, and I moved on with other ideas. I didn’t let that mistake stop me from excelling.

EMMIT PERRY A/K/A TYLER PERRY IS A THIEF AND HAS TRICKED THE PUBLIC RECEIVING MILLIONS OF DOLLARS. HE TAKES FROM MOTHERS, STEPPING ON THEIR BACKS AND PRETENDS TO BE A MAN OF GOD. THE BIBLE SAYS IF A MAN STEALS, HE SHALL RETURN SEVEN (7) FOLD. WHILE I WAS SUFFERING FROM A BRAIN TUMOR. MR PERRY WAS USING MY SCRIPT UNAUTHORIZED AND MADE 200 MILLION DOLLARS. BEFORE TAKING MY SCRIPT, HE WAS BROKE. MR. PERRY STOLE MY CHILDREN AND GRANDCHILDREN INHERITANCE. MR. PERRY GOD IS GOING TO EXPOSE YOU.