Recently I had the opportunity of visiting the studio of Francisco Araujo, a first-year Master of Fine Arts candidate at Texas Christian University. MFA programs can be wonderful for artists seeking an incubator environment to hone their craft or to network their way into professional and institutional circles. But graduate art degrees that sometimes cost upwards of $100,000 can be difficult to justify, especially in a field where graduates are more likely to get caught in the adjunct loop to fund their practice than they are to secure financially viable gallery representation or competitive tenure-track positions. That TCU offers a highly selective, fully funded three-year studio art MFA in Fort Worth is remarkable. For Araujo, a DACA recipient who worked as janitor from his middle school years through his undergraduate degree, the tuition-free program is an essential resource, he explained.

“I have never considered a path that didn’t involve an MFA,” he said. “And so far, I have been exposed to interesting ideas and come across interesting people in an art-centric milieu, which has helped me look at the world in a critical way.”

Originally a printmaker, Araujo was drawn to the immediacy and accessibility of artists like José Luis Posada and David Alfaro Siqueiros (Siqueiros was so committed to the politics of accessibility that he distributed prints via an artist-union newspaper and encouraged his audience to create street art by pasting the paper on walls). Araujo’s prints expressed an interest in the distortion of identity, using official documents (IDs, passports) and family albums as the basis for woodblock and intaglio works.

The objects currently on display in his studio abandon printing on fine art paper while maintaining process to examine the tension between the expensive materials of contemporary art and printmaking’s democratic history. In “mujer y lo negro (self-portrait),” a woodblock with the likeness of a woman, blackened with ink, stands alone as sculpture. A clear glass panel covers the relief, preserving and almost sanctifying the print matrix.

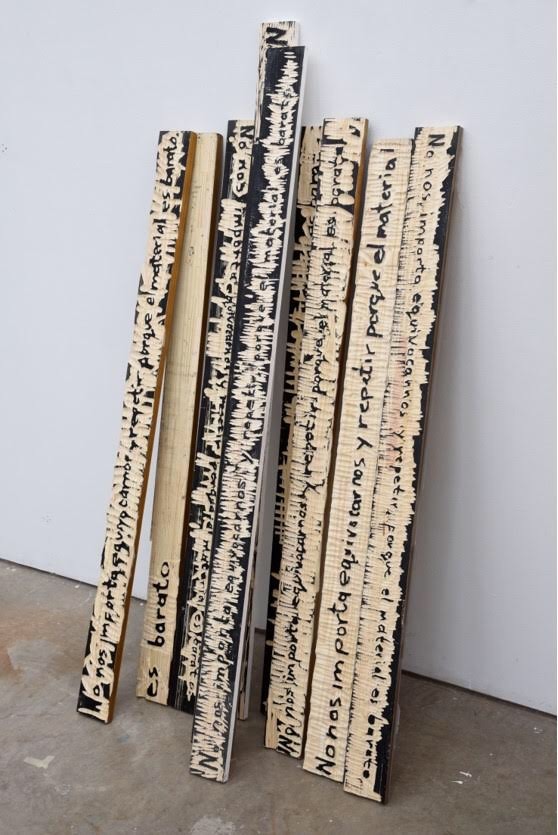

Araujo presents a more layered conversation with “Tablones,” a grouping of dilapidated salvaged wooden planks casually propped against the wall. Text engraved into the surface wood’s rough surface paint calls attention to how the labor of the artistic process transforms material. This concern with value and how it is created echoes throughout several of his works, such as a curious assemblage featuring a cigarette butt delicately balanced alongside the remains of a crushed pearl –– he developed an affinity for other people’s trash during his custodial days.

In the corner of his studio, a patchwork of reworked steel and copper plates faintly etched with the faces of family and strangers are carefully laid out on the floor. Its recessed location is a particularly poignant use of placement that effectually claims a liminal space to discuss what he refers to as his “mixed status.” The installation’s brassy surface reflects Araujo’s tenuous links to his birthplace of San Luis Potosí, a Mexican mining town he hasn’t visited since he was eight years old. The work references the faint and possibly confabulated recollections of childhood relatives and friends in his hometown that have since moved or passed away.

“I walk on forged memories,” he said.