There are two concurrent exhibitions of photography at Fort Works Art right now. In the street level gallery is Laura Wilson’s Photographs in the West, and in the upstairs gallery, Byrd Williams IV’s Memory, Imagery, and Mortality.

Wilson is a photographer’s photographer. Her black-and-white silver gelatin prints, the traditional pre-digital standard type, are large (some 46 inches squared) and bow at the edges from the weight of the photographic paper. Like most photographers who were trained on black-and-white darkroom photography, I could almost smell the developer chemicals that the oversized prints would have been drenched with as they moved from one processing tray to the next. They offer a striking tonal range and sharpness, a testament to Wilson’s decades-long experience as a master photographer.

The images also bear the heft and nostalgia of Wilson’s subjects. Her depiction of ranchers in Texas from Albany to Valentine and beyond, along with images of women and girls from the secluded Hutterite community of Stanford, Montana, reveal a simplicity and nobility that are part of America’s biographical myth. It is the narrative of a group of hardscrabble settlers taming nature and beasts with the good Lord’s blessing, onward to a manifest destiny, proclaiming virtue and providence.

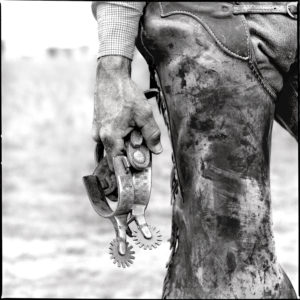

No two images from Photographs in the West demonstrate the concept of simplicity and nobility more than “Hand and Spur Y-6 Ranch Valentine, Texas, June 3, 1992” and “Emma, Hutterite Girl in Field.” In “Hand and Spur,” the figure is cropped to fill more than half the frame, with a smudged hand holding spurs that almost touch mud-covered chaps. It is a literal ranch hand and a stand-in for the dirty work that happens where roughnecks and ranches meet. The suggestion of hard work and a rough life are all too evident.

In the “Emma” composition, the subject is as poetic as she is poignant. She stares toward the horizon, facing the wind, unmoved. Her neatly pulled-back hair is tucked in an almost perfectly tied triangular polka-dotted bonnet as the wind blows her simple checkered skirt. Her stance in the wheat field is either that of defiance or of harmony with nature.

To say that Wilson’s images continue an idealized version of the West is to acknowledge the early photographs that typify the genre going as far back as the photographs of William Henry Jackson in the late 1800s. Jackson’s photographs of Wyoming and Yellowstone all but established what would become a feedback loop between adventurous types heading across barren plains, intrigued by Jackson’s pictures, and these same land grabbers becoming the story of the region.

The tradition of photographers heading into the plain states continued with Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Walker Evans, and others, all creating their own versions of the American West. In 1979, Wilson accompanied Richard Avedon on his journey that was commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. The result was the iconic exhibition In the American West. Images of Texans from that show were re-exhibited last spring at the museum and showed a variety of us, including migrant workers, truck drivers, cashiers, and oilmen.

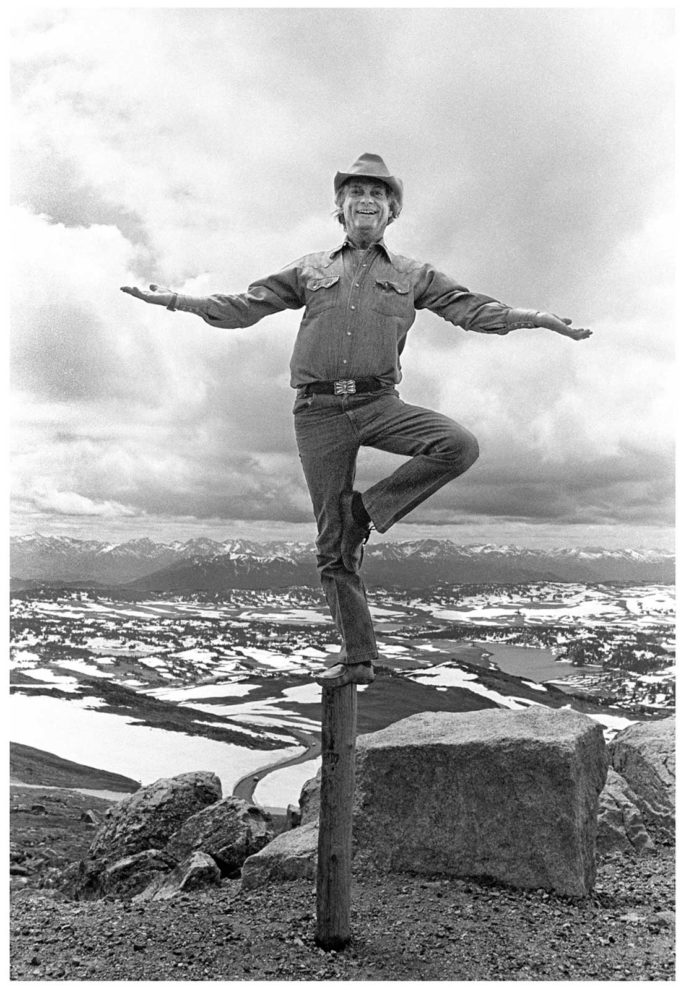

Photographs in the West is Wilson’s version of the land and the people. It also represents the nostalgia and performance of the West popularized by old Marlboro print advertising and Western TV serials and movies. There is a picture of Avedon balancing on a pole in Wyoming, a Hutterite boy standing on a horse, and even a stunt cowboy falling off a horse. But one image stands out in this performance of the west and perhaps reveals a connection between Wilson and her movie star sons Owen, Luke, and Andrew.

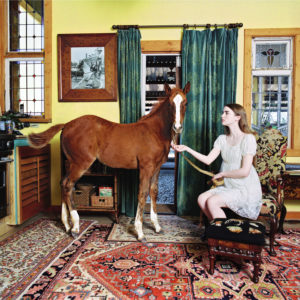

The image is “Girl and Colt in Living Room, Weatherford, Texas, May 8, 2006,” and it is as Andersonian as a photographer can get. Indeed Wilson has photographed on many of Wes Anderson’s movie sets, including Bottle Rocket, The Darjeeling Limited, and The Royal Tenenbaums, and his stylized, nostalgia-soaked movie sets are frequently populated by the Wilson brothers. In “Girl and Colt,” a seated girl in a white dress stares admiringly at a colt in a living room. There are lush carpets with intricate designs and a green silk curtain drawn just enough to reveal a graveled pathway, and the walls are a canary yellow. A picture of a cowgirl standing on a falling horse hangs above the colt, and the stretch to find Anderson’s influence on Wilson becomes easier to make.

But what Wilson’s work also reveals is that she has long since found her way from behind the scenes of her collaborators and created images that are her own private West. The Hutterite girls are part of their environment, not detached from it and isolated in front of sterile white backdrops. There is a feeling of presence. And her cowboys, even when they are trotting across the plains or staring right into the camera, reflect back a kind of ease that is neither pretentious nor uncomfortable.

Williams’ images are also a kind of nostalgia and remembrance. With Memory, we take a deep autobiographical dive into the Fort Worthian’s world and revel in his memories of people, homes he’s lived in, and the reckless abandon of childhood. His unflinching look at family deaths results in macabre collages of old photographs, death certificates, and coroner’s reports. In “Timmy Got Bullets,” these elements are all present, along with a typed quote from the deputy chief of police about the shooting death of Timothy Lee Williams. The soft focus and dream-like appearance of Williams’ images also make them feel like our own fuzzy memories. His childhood photographs of boys reenacting the battle of the Alamo or his images of neighborhood girls seem to come more from inside his head with some futuristic Black Mirror tech than from his camera.

Both photographers offer a view of the past that hopes to engage us in the present. But the power of photographs is also a cautionary tale about the stories they tell. In the end, it takes a lifetime of images to reveal all of a place, or all of a person, a truth not lost on Williams or Wilson.

Christopher Blay is an artist and writer with a BFA in photography from TCU. He is also curator of the Art Corridor Gallery at TCC.

Fort Works Art

Laura Wilson: Photographs in the West and Byrd Williams IV: Memory, Imagery, and Mortality both thru Feb 3 at 2100 Montgomery St, FW. Free. 817-759-9475.