Painter Sam Swihart’s “Cosmetic I,” “II,” and “III” is a grotesque series of black-and-white portraits depicting morbidly disfigured faces. The three male subjects are painted in close-up perspective, and each figure has a pair of red lips superimposed over his mouth. The lips are painted on strips of paper held over their faces by fingers with painted nails. It’s as if they were plucked straight out of central casting for the role of Joker in a twisted sequel to society’s version of Batman. In that sense, these paintings are also thrust onto the viewer, forcing us to confront our flaws and sicknesses.

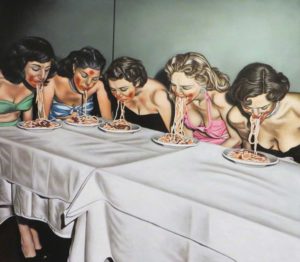

Swihart’s paintings are rooted in his concern with what he describes in his artist statement as “the torturous pursuit of ideal beauty and the moral dilemma that it entails.” In one of his other paintings in Unplugged, a four-person group show at Gallery 414, Swihart recreates the famous 1948 photo “Women in a Spaghetti Eating Contest.” With his faithful recreation of the photograph, Swihart paints the five Broadway showgirls who appear to be in their underwear trying to finish a bowl of spaghetti without using their hands. There is nothing beautiful about this painting beyond Swihart’s ability to recreate what is in the photograph. The showgirls are tragic figures performing their beauty in an ungraceful scenario, as if to demonstrate that their beauty transcends the performance.

Swihart’s paintings are rooted in his concern with what he describes in his artist statement as “the torturous pursuit of ideal beauty and the moral dilemma that it entails.” In one of his other paintings in Unplugged, a four-person group show at Gallery 414, Swihart recreates the famous 1948 photo “Women in a Spaghetti Eating Contest.” With his faithful recreation of the photograph, Swihart paints the five Broadway showgirls who appear to be in their underwear trying to finish a bowl of spaghetti without using their hands. There is nothing beautiful about this painting beyond Swihart’s ability to recreate what is in the photograph. The showgirls are tragic figures performing their beauty in an ungraceful scenario, as if to demonstrate that their beauty transcends the performance.

John Hartley has curated a well-balanced exhibition with Unplugged and cleverly constructs the show to explore dark themes in these figurative works. Rachel Black’s paintings from her family photos are no exception. In “Fruition,” a dinner table is set with Christmas colors. There are wine glasses and cups filled to the brim and what appear to be burgers and fries are neatly set around the edges of the table. A woman alone stares off to her right, perhaps in contempt or resignation. The ideal dinner scene is skewed. It is the exact opposite of a Norman Rockwell holiday feast, where the labor of the matriarch goes unappreciated and the feast goes unattended. Melancholy reverberates in these scenes meant to be festive events and threads Black’s paintings together.

“Share Alike” is another example. The photographic effect of a flash-lit image highlights the foreground and plunges the background into darkness and harsh shadows, which Black renders with thick, impasto brushstrokes that make the surface resemble the cake in the picture. But in “Share Alike,” the cake is hardly decorated, the figure in the foreground, back turned toward the viewer, is neither happy nor sad, and the one face we see in full perspective is in the shadows.

What these paintings show is not a celebration of the past but a harsh and honest look at a past that Black describes in her statement as “deceptively rose-colored.”

Unplugged also features Jamie Damon’s charcoal and pastel drawings of celebrities in gas masks, the most prominent of whom is Bill Murray. In “Apocalyptic Bill,” Damon depicts the actor as a blue-eyed, expressionless figure with the mask on his head. This is the only expression that could be expected of Murray, even in the face of the apocalypse. Although the scale of the drawing, approximately 20 inches by 24 inches, feels majestic and even regal, it portrays a wry and defeated Bill perhaps signaling abandonment and defeat versus preparation for survival. It seems to suggest that we too should remove the mask and surrender to the all-consuming fire.

Interspersed among the other works in Unplugged is Kate Stipp’s Tea Party series: a group of small oil paintings showing women precariously balancing teacups on their heads. The masterfully painted portraits, some on panel and others on canvas, hover on the surface of lush pastel backgrounds, some of which are covered in blossoms that repeat in the teacups and saucers placed on the heads of the women in the paintings. They are reminiscent of the paintings by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the mid-19th century, whose allegorical subject matters aspired to a more classical sentiment. Stipp’s paintings, however, find her subjects emerging from their stylized backgrounds with enough grace to balance our expectations with their transcendence. Even when that emergence feels a bit shaky, the subjects’ rigid poses defy uncertainty to reveal poise and complexity.

What Kate, Jamie, Rachel, and Sam collectively reveal in Unplugged is a disconnection from preconceived notions and expectations that anchor us to the past or deny us a connection to the richness of the present. Beauty, nostalgia, and expectations are our ways of understanding each other, and Unplugged urges us toward a deeper connection to that understanding.

Unplugged

Thru Jan 7 at Gallery 414, 414 Templeton Dr, FW. Free. 817-336-6595.