On a quiet Friday morning at the Mud House Cafe on Cherokee Street in St. Louis, I stared outside at streets still wet from a storm the evening before. It was the middle of summer, and small pools of water on wooden tables reflected the cafe’s hand-painted sign. A knock-off Frank Stella mug from the 99-cent store on Camp Bowie held my coffee as I did some reflecting of my own.

Most artists find it impossible to take a vacation and leave it at that. Our minds are constantly on, and the temptation to transform experiences into subject matter for our next project can be irresistible. What was meant to be a summer break visiting familiar faces in unfamiliar cities quickly turned into a 4,062-mile road trip and writing junket through the Midwest, the Northeast, and the South. Over the three weeks last August, I started a new body of work, continued another that took me to sites of police killings in several cities, and visited a few exhibitions with ties to Fort Worth. It was also a long drive back in the direction of photography. I began making pictures in my early 20s, and a decade later, I walked away from the medium. Now 12 years on, I embarked on this trip partially to reconnect with Polaroids and photography.

A couple of months before Polaroid Project, an exhibit at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art that, sadly, I didn’t get to write about, my former photography professor Richard Doherty approached me about working on an exhibition proposal with him. Lucas Samaras, William Wegman, and other iconoclasts of photography, some of whom were included in the Polaroid Project, transported me back to his classroom and my formal introduction to the Polaroid process.

In planning my trip, I soon realized that my show with Richard could be a body of work that was about photography –– not only images themselves but the process –– and that long journey back. The series I began was about making portraits using a machine, a special kind of Polaroid camera, one that was designed to photograph other machines (oscilloscopes, which measure electrical signals). The camera, a Polaroid Tektronix C30, has a depth of focus of only between 1 and 3 inches, which can make for extreme close-up portraits. I was curious about how setting up a system of restrictions –– photographing only strangers, to remove the familiar; extreme close-ups; expired Polaroid film; and doing all of this in places I’d never visited –– would expose the limitations of photography, if any. I stopped making photographs because I felt as if every photograph I saw had already been made. It wasn’t a matter of making a novel image but rather feeling as if the medium itself had been exhausted. Putting these restrictions on the process was a way of pushing against limitations. The proximity to my subjects engendered discomfort, intimacy, invasion, and scrutiny, producing some unpredictable results, conversations, and negotiations of personal spaces. I hoped this would lead to some more questions about photography, and St. Louis was my first stop.

In planning my trip, I soon realized that my show with Richard could be a body of work that was about photography –– not only images themselves but the process –– and that long journey back. The series I began was about making portraits using a machine, a special kind of Polaroid camera, one that was designed to photograph other machines (oscilloscopes, which measure electrical signals). The camera, a Polaroid Tektronix C30, has a depth of focus of only between 1 and 3 inches, which can make for extreme close-up portraits. I was curious about how setting up a system of restrictions –– photographing only strangers, to remove the familiar; extreme close-ups; expired Polaroid film; and doing all of this in places I’d never visited –– would expose the limitations of photography, if any. I stopped making photographs because I felt as if every photograph I saw had already been made. It wasn’t a matter of making a novel image but rather feeling as if the medium itself had been exhausted. Putting these restrictions on the process was a way of pushing against limitations. The proximity to my subjects engendered discomfort, intimacy, invasion, and scrutiny, producing some unpredictable results, conversations, and negotiations of personal spaces. I hoped this would lead to some more questions about photography, and St. Louis was my first stop.

My Airbnb was down the street from The Blue Pearl, a bar where I encountered my first few subjects. My approach was simple. I ordered a drink at the bar, a Kirin Ichiban Japanese brew, and explained my trip to the bartender. I asked Jay at the Pearl if I could come out the following night for open-mic and introduce the project and myself. He agreed, and I was back with my camera the following evening, photographing Jay, Jared, Jesse, and Chuck. The conversations we had were far removed from photography. We talked about our childhoods, the neighborhood, and Jay’s coming out to his parents. I immediately realized that what I didn’t want to do was connect these personal stories and conversations to the project. It seemed more than sufficient to focus on what the images could mean in the context of how they were created than to essentially recreate the popular series Humans of New York, in which photographer and blogger Brandon Stanton makes portraits of ordinary New Yorkers and interviews them. My approach to making these photographs would be to reveal the camera for the machine that it is, by photographing with one that is stripped of fancy grips, reduced to just an aluminum alloy body and some black leather, showing only its mechanical nature. After a couple of unsuccessful prints, clearly due to the age of the old film and not my rusty photographic skills (definitely not), I was able to make about six images. The project had begun.

Open-mic night was everything you would hope it would be at a place called The Blue Pearl. The street was quiet, and the door was open. The Pearl’s floor-to-ceiling windows invited passersby, and a few of them came in. It was a club of regulars in a neighborhood where outsiders rarely visited. The lingering voices singing the blues and the slam poets dropping knowledge were interspersed with loud conversations and couples snuggled in dark corners of the tiny shotgun space. I wasn’t allowed to be a fly on the wall, and my project quickly became secondary as conversations with neighbors continued. I had found the right place and couldn’t have hoped for a better introduction to St. Louis.

The following day, I went to see Blue Black at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, curated by artist Glen Ligon. The artist-as-curator concept is probably an overreach from the perspective of curators, particularly in an era when everyone is a curator and everything is a “curated” experience. Suffice to say that there is a distinction to be made between curators with credentials and people (artists) who put together exhibitions.

To his credit, Ligon avoids all the pitfalls that one might expect from this exercise. With its breadth of scholarship and choice of media (paintings, video, photographs, and sculpture spanning 50 years), the exhibition emerges as both a literal survey of color and a reflection on its social, spiritual, and scientific implications. The art in Blue Black, inspired by the colossal Ellsworth Kelly wall sculpture of the same title, is hung in a way that reveals hidden relationships among the pieces, and also demonstrates the same intention and deliberateness of Ligon’s own work, which was in his solo exhibition at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in February, 2012.

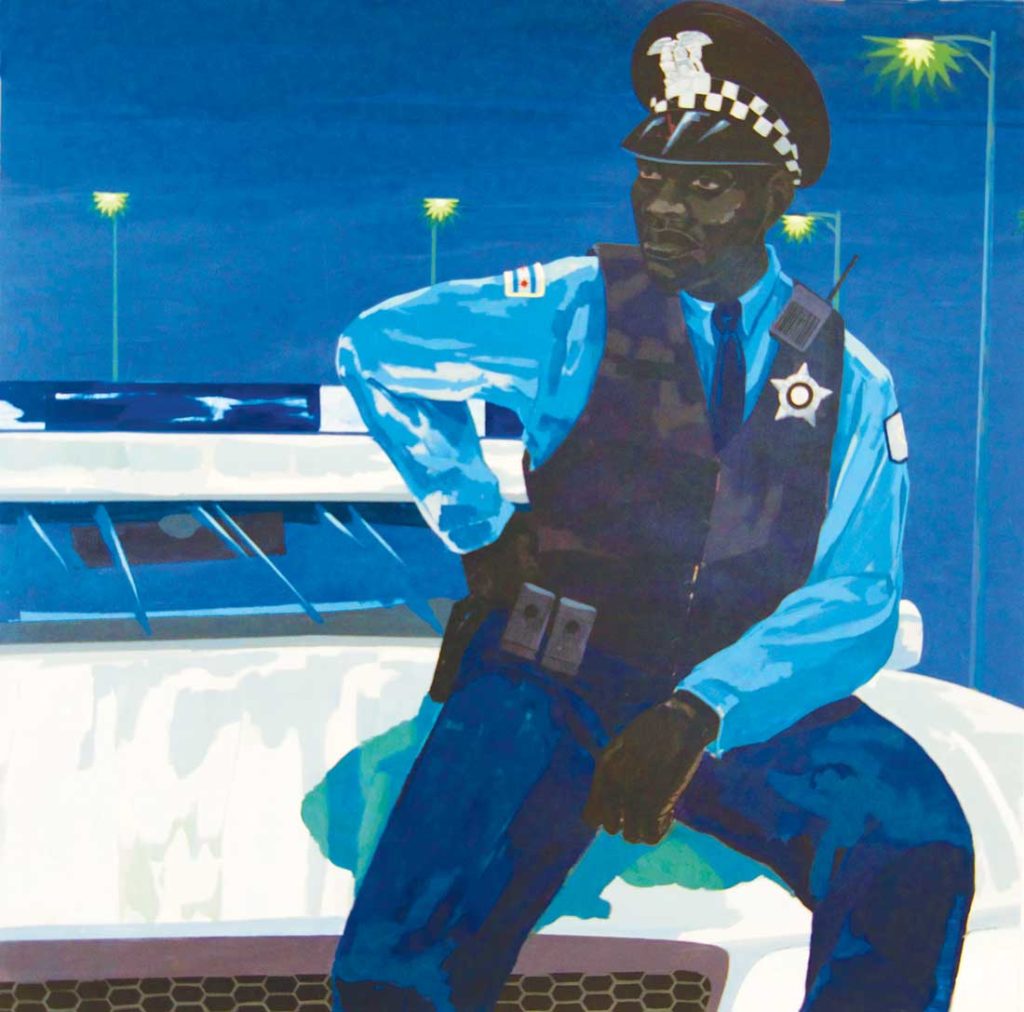

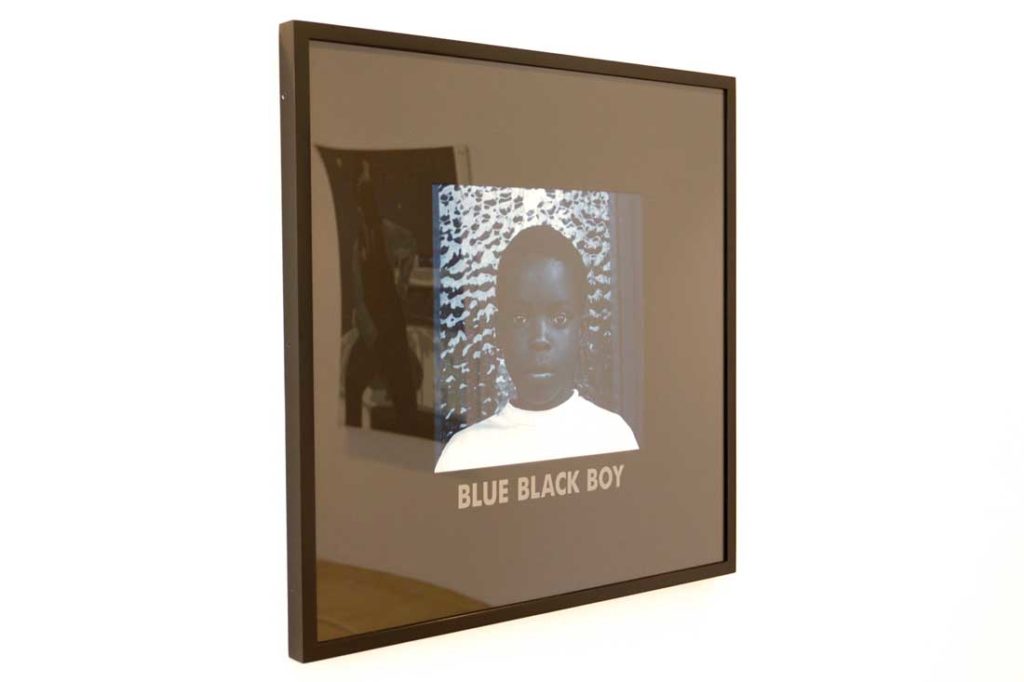

In the entrance gallery, Kerry James Marshall’s “Untitled (policeman)” is reflected in the frame of Carrie Mae Weems’ “Blue Black Boy,” which hangs next to it. This juxtaposition of images, a painting of a Black police officer next to the photograph of a little African-American boy, only begins to unpack the layers of interpretations that can be read into this proximity, considering the historical relationship between the police and African-Americans.

The fuel of that tense and sometimes deadly relationship ignited in Ferguson, Mo., 10 miles northeast of the museum, back in 2014 when Michael Brown was killed by police. In that year alone there were three other police-related killings that dominated the headlines: Eric Garner (Staten Island, July 17), Laquan McDonald (Chicago, October 20), and Tamir Rice (Cleveland, November 22). And despite a travel advisory issued in June by the Missouri chapter of the NAACP, I wanted to visit the site on Canfield Road for myself. For the past year, I had seen these spaces only on Google street view, and as I imagined, being there was a completely different experience. I was struck by the serenity. The trees along the sidewalk were like sentries, watching over the bronze plaque that commemorates his life. While at the site, two couples driving by stopped and walked up in silence, embodying the grief that I imagined we were all feeling. I was glad that I made the pilgrimage.

I left Ferguson and headed for Chicago around noon, hoping to get there before sunset. The last thing I wanted was a repeat of my arrival in St. Louis around 11 p.m. a few days earlier, a Black man stumbling around an unfamiliar neighborhood, looking for his Airbnb.

I arrived in Chicago, just after rush hour, to a cool 68 degrees. My place was near Douglas Park, on the city’s West Side, and across the street from the Lagunitas Brewing Company. I went over for a beer as soon as I settled in, but they were closing for the evening. After I told them I drove all the way from Fort Worth for a beer there (technically true), the host Tim handed me a six-pack of their Sucks Brown Shugga’ Substitute Ale and a 12-pack of their 12th of Never Ale. I know Southern hospitality, but I have yet to leave a Texas brewery with 18 free beers in hand. (I’m looking at you, Rahr!)

The next day, in between catching up with a college friend and roaming the city in search of an authentic Chicago food experience, I had a few hours to visit the Murakami exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art which comes to our Modern sometime next fall. I felt lucky to preview the paintings, drawings, and sculptures beforehand.

It became immediately apparent that Murakami’s work would transform my superlatives about the experience into clichés. The scope of subject matter alone (post-World War II Japan, consumerism, contemporary culture) is daunting enough, but it becomes too much to summarize when considering the connection to centuries of Asian traditions and methods that he uses in his work. The painting “69 Arhats Beneath the Bodhi Tree” is peopled with both gargantuan and dwarfed figures ranging from the grotesque to the benign. Demons, dragons, and all manner of fauna stare back at eyes curious enough to step in for a closer gaze. The acrylic and gold-leaf painting is in two large sections, each 33 feet long, with 10 panels in all. They stretch across one of the long corridor walls at the MCA. The walls, painted black, were a strong contrast to the bright colors of the gold-and platinum-leafed painting.

However monumental this painting may be, the connections I anticipate a Fort Worth audience will make to it is its similarity to KAWS, whose Modern exhibit came down only a few months ago. The artists even collaborated on “Kawsbob Enters the Strange Forest” for Murakami’s auction benefiting earthquake relief in Japan in 2011. Although most curators would downplay this seemingly superficial connection, it’s pretty hard to ignore. Another popular piece in the show was the Graduation cover for Kanye West’s 2007 third album, which will hopefully be a part of the traveling exhibition to Fort Worth.

After the museum, I continued with my extreme close-ups project, which so far had a pretty slow start. It was redeemed only when on my last day in the city I visited Anish Kapoor’s “Cloud Gate” in Millennium Park. I made two trips there on my final evening and in between, I got a Vieux Carré (cognac and rye) at The Gage, a bar that faces the park. After taking a few pictures with the rest of the tourists at the “Gate,” I was able to make a couple of portraits, including “Taylor at ‘Cloud Gate.’ ”

Before I left Chicago the next morning, I drove out to 4100 South Pulaski Rd. on the city’s South Side to the site of Laquan McDonald’s killing. The grainy dash-cam video from that fateful October evening nearly three years ago shows the arrival of Chicago police and the subsequent firing of 16 rounds into a knife-wielding McDonald from about three feet away. I wasn’t prepared for the return to normalcy at these sites, from Ferguson to later in New York City. The makeshift monument to Eric Garner on Staten Island and the mural to Amadou Diallo in the Bronx are all that is left of the events. It is as if we are willing to forget only to be surprised another generation from now because we didn’t acknowledge the underlying problems that led to these killings.

After getting out to shoot some video and walking the site, I hopped back onto the freeway and eventually onto I-90, which was one of many toll roads that I had definitely not budgeted for on my trip. With a brief stop in Cleveland to the site where 13-year-old Tamir Rice was killed, I continued on to Pittsburgh.

Arriving after midnight, it was another debacle of trying to read house numbers on insufficiently lit, unfamiliar neighborhood streets. And considering the conversations on my neighborhood association’s Facebook page about strangers knocking on their doors at night (with security cam footage in full supplement), I was more inclined to sleep in my car than continue searching. Fortunately, I was able to reach my host, and, once in, I decided to forgo a shower and crashed on the loft’s very comfortable bed.

Following my editor’s recommendations about places to go in his former hometown, I had a totally different experience the next day. I enjoyed drinks at the Elbow Room in the tony Shadyside neighborhood and breakfast at the world-famous DeLuca’s in the Strip District. As with most stops on this trip, I wish I had more time and an expense account. But, frankly, it might have all gone to tolls and parking.

I left Pittsburgh around noon and arrived in Brooklyn just before rush-hour traffic. I found a parking spot in front of the apartment of my friends John and Lake in the quiet neighborhood of Ditmas Park. One short bus ride later, I was on Linden Avenue, with “Back in the day, on the boulevard of Linden” playing in my head. As I got off the bus and walked toward two other friends’ place, it brought back memories of earlier trips to the city and other song lyrics from A Tribe Called Quest. I met these friends, Chris and Erin, about a decade ago when they came to Fort Worth to collaborate on the Cowtown Puppetry Festival at Hip Pocket Theatre.

My Brooklyn welcome was a warm one, seated at a feast of fresh summer veggies and great catch-up conversations with my hosts. Claudia, another Fort Worth transplant, came over, and we reminisced about our dinners and brunches from a few years before. I also met a few neighbors and would later go out to Christopher’s studio a few miles away and catch up with him about upcoming projects. But at that moment, we were being treated to a sampling of the food Erin was planning for the Illuminati Ball, a bacchanalian affair that The New York Times described as a “decadent ‘immersive excursion’ … featuring a nine-course dinner and exotic cocktails, masks, ‘anthropomorphic escapades’ and initiation rites.” Our dinner was a lot tamer than that, and my first evening in Brooklyn was a success. After dinner, I took a car back to Ditmas Park, planned for the following day, and got some well-deserved rest.

The next morning, I took a walk through Ditmas Park to Milk & Honey Cafe, where I had my first cup of Brooklyn coffee while figuring out a strategy for the day. After breakfast, I drove into the city and a met up with my friend Heidi at the Whitney Museum. We went to see Alexander Calder’s Hypermobility, a series of the artist’s famous mobiles, and Hélio Oiticica’s To Organize Delirium, a dense interactive beach-scene installation laid out in the gallery, complete with potted plants and tent-like beach houses. Looking at the Whitney’s Calder mobiles. I couldn’t help but think about his “Untitled” mobile at the Amon Carter, the red, blue, and yellow hanging sculpture that has its own spot in the corner of a second-floor gallery at the museum. And it also brought back the stinging loss of Calder’s “Eagle,” a massive outdoor sculpture that was once an icon in front of the old Bank One building downtown. Sold in 2000, it was eventually installed in Seattle’s Olympic Sculpture Park.

I spent the next few days in New York visiting familiar places and retracing my steps from over a decade ago when I last was in town. Of all the places on my list that I was eager to check off, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, St. John’s Cathedral, The Hungarian Pastry Shop, and Washington Square Park, I saved my excitement for a little park bench in Rockefeller Park. There, in the former shadow of One World Trade Center overlooking the Hudson River, is a series of little bronze sculptures by artist Tom Otterness, titled The Real World. The installed landscape is full of little people and animals pushing bronze pennies up hills and streets, and fat bronze cats being carried on platforms toward idols, with frogs and giant sculptures of heads and fists darting their tiny little land. I stumbled onto this public art cluster in the late ’90s on one of my many trips to visit friends in the area, and it was always a touchstone for me. It was one of the first parks I discovered on my own when I first visited the city, and it was the spark that inspired me to continue exploring new places without maps.

Earlier, I had time to visit my buddy Nathan. We spent a couple of hours on the rooftop of his apartment building. The former member of Austin’s OK Mountain art collective and former Dallas resident treated me to his local watering hole near Washington Square park, where we had a couple of beers and talked about what we were doing and making in our studios. One thing that came up was the question most artists wrestle with: How can our work speak to our time? It’s tricky when art becomes a prescription for what is wrong with the world, as Kara Walker’s recent exasperated declaration of an artist’s statement makes abundantly clear. But while there is a risk of activist art becoming trite and falling into irrelevance, or exhausting its progenitors at the minimum, there is also a politic in avoiding the world around us and getting lost in conceptual and philosophical gestures.

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 at the Brooklyn Museum succinctly addresses this question. I saw the show the following day. With its focus on a diverse group of women of color working in that period as artists and activists, the exhibition featured a variety of media by women who lived and worked at the intersection of social upheaval and radical political movements. It is both a testament to the power of art to influence social change and the futility of art as a panacea for our sociopolitical woes. The caveat of course is that some of the political posters, videos, and sculpture in Black Radical Women function somewhere between this activism and the avant-garde. Betye Saar’s “Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail” is one example. The mixed-media assemblage was made from a green wine jug with a mammy figure on the front and a black-power fist on the back, and it was fashioned into a Molotov cocktail, with commentary on radicalism and a critique of racist stereotypes of black women. Curators Catherine Morris and Rujeko Hockey organized a powerful and prescient exhibition that reads more like the Women’s March on Washington earlier this year than a focus on a generations-old political landscape.

Feeling charged and fired up by my Brooklyn experiences, I was sad to leave John and Lake’s. But I was also excited to experience Washington, D.C., and continue with the project I was now calling Portraits with Strangers.

By mid-afternoon the next day, I was walking up to the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). Making my way past D.C.’s neo-classical pantheon of museums, I was the guest at a party where I knew only one person and couldn’t wait to find her. But then there she was, poking out from behind the tree-lined sidewalks, obscuring the Washington Monument in all its grandeur, beckoning visitors who swished by me with ever-increasing speed and determination, as if the building with all of its promised treasures would somehow disappear before we could get to it.

I won’t go into the details about how I managed to enter the museum (legally), avoiding standby lines, ticketing, or reservations, but suffice to say that I did that very thing, in no small part due to an overwhelming charm offensive and a lot of determination.

Once inside, I took the escalator in leaps and bounds, making my way to the entrance of Musical Crossroads, an exhibit that occupies the entire top floor. I must have spent over an hour in that section alone. “It’s too much!” I overheard a woman say. “We have to take a day.” Exactly, I thought. What better conclusion to make in the middle of this experience than to be overwhelmed by the amount of history in this one exhibit and the encyclopedic building. The first thing I saw past the entrance with its semicircular display was Chuck Berry’s red 1973 convertible Eldorado. A Cadillac, for better or worse, was once recognized as the pinnacle symbol of success in the African-American community. Placing his Caddy at the entrance of the gallery is both a nod to that symbolism and a strong introduction to Berry’s contribution to the American experience. Everything, from the Parliament Funkadelic spaceship to the displays that contained artifacts of hip-hop culture (Radio Raheem’s boom box, J.Dilla’s Akai MIDI 3000), revealed the Smithsonian’s steady curatorial choices over Musical Crossroads. I was black Indiana Jones, and this was the Ark of the Covenant. I was at the holiest of holy sites with nearly every significant contribution that black folks have made to American culture within reach.

Moving down to the second floor, I was awestruck by the building’s architectural accents: the bronze-colored metal lattice façade, an homage to the intricate historical ironwork crafted by Southern slaves, and the windows looking out to the Washington Monument and the Capitol Building.

Some of the exhibitions in the NMAAHC were anticipated, like the section dedicated to sports heroes and a celebration of the inventions and scientific achievements usually omitted from history books. But in a corner of the second-floor exhibition, I saw a phrase that I heard my parents use very often as a kid when faced with the struggles of raising a large and extended family of my siblings, cousins, and neighborhood children: Make a way out of no way. It was a profound statement that spoke to the resilience I saw in my parents and that I look for in myself. It was a phrase that was speaking directly to me and to the African-American experience.

There was so much more of the museum that I wanted to explore, but after hanging out there for the better part of two hours, I decided I would have to make a return trip to D.C. I met up with my cousin Gail later that evening for some D.C. nightlife, and a couple of drinks later it was time to call it a night and head back to my cousin George’s. I needed a good night’s rest for the drive to Richmond, Virginia, in the morning.

This was the last leg of my trip, stopping in Richmond and Birmingham before heading back to Fort Worth. I spent an evening at the place of my friends Jim and Chrystal in Richmond, and we went out for beers at Hardywood brewery, where I picked up a bottle of Hardywood Bourbon Cru. On the way back to their place, I got a tour of some of Richmond’s Confederate monuments and the Hollywood cemetery. The next morning I met new Richmond residents (from Dallas) Noah and Margaret for brunch. It was so good to touch base with familiar faces, but after a brunch that was way too short, I was off to Birmingham to meet up with my college friend Sheri on the final stop before Fort Worth.

The thing that happens on a quick overnight trip is that your hosts want to show you the entire city –– you wish you had more time. The thing that wins the day, however, is having unexpected moments. While driving back from downtown Birmingham, we followed a bellowing cloud of white smoke to a house on fire. We got there at the same time as the fire department and stood in the terrifying glow of the flames. We watched as the firemen battled the blaze. We were told to move back before too long but not before I took some pictures. The image of the burning house stirred up memories of photographs from the 1960s South, and as tiki torches would soon burn in Charlottesville, it seemed an ominous premonition.

In the months since my return to Fort Worth, the country has seen both the carnage of a protester being run over and killed and an entire state mobilizing to be good neighbors to a city engulfed by floods. But whether it’s Charlottesville or Houston, what my summer road trip taught me is that we are a complicated lot and that 250 years may prove barely enough to figure out this democracy’s promise of justice and equality. Driving into a violet sunset, I greeted the “Welcome to Texas” road sign with the same enthusiasm I had for the “Last Taco Bueno” mural at the fast food stop on my way out of the state. They both provided a beautiful, comforting familiarity that I didn’t realize I would need, or miss so much. This sentiment is rife with its own ambiguities, because at the same time that our state legislators threaten the rights and health of so many, citizens of all kinds are banding together and standing together. And for a brief moment last summer, and hopefully in the not-too-distant future, we will stand together as true neighbors in this beautiful Texas, full of the most diverse communities, food, art, and landscapes. After days of 55mph speed limits, expensive parking, heavy tolls, and driving in New York City, I was practically jumping out of my seatbelt at that sign. Welcome to Texas, indeed.