One could characterize Wild Spaces, Open Seasons: Hunting and Fishing in American Art, on display at the Amon Carter Museum through January 7, as an exhibition about sport. The paintings and sculptures on display offer American artists’ depictions of a pair of prominent outdoor sports.

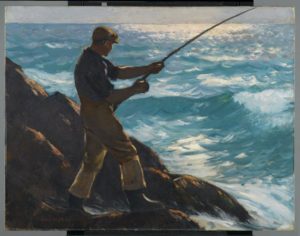

We think of sport as something one does for enjoyment, and many Americans hunt and fish to relax. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates the country’s population contains nearly 36 million anglers and some 11.5 million hunters. Some might enjoy solo recreation, as in Gifford Reynolds Beal’s The Fisherman. Others prefer a recreational experience with friends, often accompanied by a round of post-excursion disputation, as seen in John George Brown’s Claiming the Shot: After the Hunt in the Adirondacks.

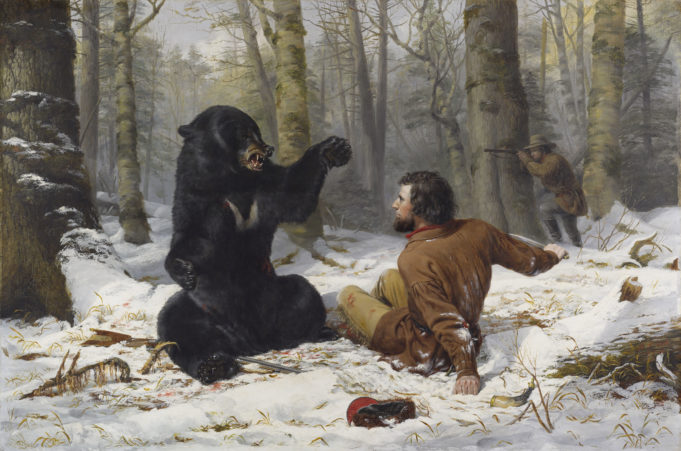

Much of the exhibition’s art doesn’t depict what we might think of as sporting, though. A competitor engaged in a game involving knife-fighting a bear, as in Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait’s 1856 painting A Tight Fix – Bear Hunting, Early Winter, would have a short career.

In place of jolly hunting parties, we see men and women pursuing game for the reasons most humans would have up until the last century: survival. The tribesmen engaged in Charles Russell’s Buffalo Hunt (or those in Alfred Jacob Miller’s painting of the same name) no doubt risk their lives bringing down a great horned beast not for the thrill of the chase, but because hungry family members await their return. John Quincy Adams Ward’s The Indian Hunter bears the look of someone who knows he must brave danger to eat (as does his dog).

![Charles M. Russell (1864-1926); The Buffalo Hunt [No. 39]; 1919; Oil on canvas; Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas; 1961.146](https://www.fwweekly.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Buffalo-Hunt-cat58-russell-300x191.jpg)

During the 19th century, the American experiment had begun to set the stage for hunting and fishing to transition from subsistence occupations to widespread recreational pursuits. Agricultural innovations and the Industrial Revolution made it possible for the masses to move beyond spending long days at labor just to produce a day’s food supply themselves. They could now trade a shorter period of less taxing work for provender generated by a smaller number of more efficient agricultural producers. Fewer and fewer Americans needed to pick up their guns, bows, nets, or poles to feed themselves. When they did so, it was because they enjoyed it.

So if you think of Wild Spaces, Open Seasons: Hunting and Fishing in American Art as an exhibition of sports art (fitting in well with other sporting elements in the Amon Carter’s collection, as documented here and here), that’s fine. While there are still many who work in the commercial fishing industry (and a few who hunt wild game for a living), most of us do have the luxury of viewing hunting and fishing as more pastime than profession.

It’s because we have more time – a lot more time – than our hunter/gatherer ancestors for fun, including sports (and visiting art museums). This exhibition thus shows more than just beautiful works by accomplished artists. It also shows progress.

Wild Spaces, Open Seasons: Hunting and Fishing in American Art is on display at the Amon Carter Museum through January 7. Caught on Paper is a supplemental exhibition inspired by Wild Spaces, Open Seasons. It features 50+ outdoors-themed works on paper from the Amon Carter’s collection. It will remain on the walls through February 11.