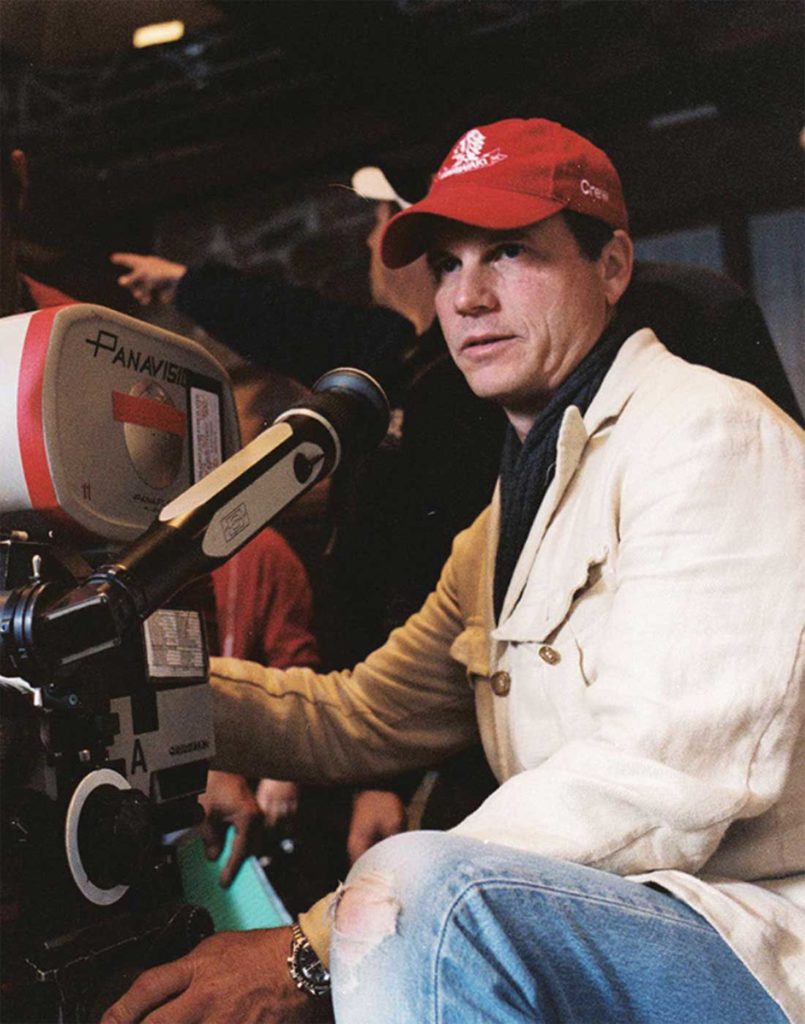

“I’m a good actor, but I’m a much better director,” Bill Paxton told Canadian film critic Jason Gorber in 2011, adding that he wished to be reevaluated.

On February 26, 2017, the day after Paxton died unexpectedly of complications from heart surgery, Vanity Fair’s Nathan Rabin entitled his memoriam “Frailty Proved that Bill Paxton Was an Auteur as Well as an Actor,” referring to his directorial debut from 2001. On the same day, Paxton’s frequent collaborator James Cameron (Titanic, Avatar) said, “Bill was a consummate artist … with a magnetic ability to draw everyone around him into his vortex and get them excited about his ideas.”

Taking off from those points, Chad Matthews, artistic director of the Lone Star Film Festival, has programmed six films — three shorts and three features — that Paxton produced or directed for this year’s event, Nov. 8-12, in Sundance Square.

“I’ve always admired people who consider the big picture,” Matthews said. “Bill Paxton was as brilliant behind the camera as he was in front of it. It’s proper that we acknowledged him as a total filmmaker.”

The festival is inaugurating an annual prize in Paxton’s honor for multidisciplinary artists in the entertainment field.

But how seriously should anyone take Paxton’s relative assessment of his acting versus his directing skills?

Having been Paxton’s friend and associate for more than 45 years, I know for a fact that he preferred to be in charge on any given project. He had a great sense of aesthetics, a deep regard for his audience, and a good eye for material. Acting was his “day job” — how he made a living and supported his family, but he considered himself an artist. Movie stardom was the means to an end, not the end game. It was really hard for him, having no control over his art, that is, the films in which he acted but didn’t direct or produce. So why didn’t Paxton start directing earlier? In fact, he began experimenting with filmmaking very young in high school at Arlington Heights.

On March 1, 1973, after Paxton had graduated and while I was in my junior year at Southwest High, we met on a plane to London with 20 other kids from our two schools. We were on our way to Richmond College, an American-owned liberal arts school affiliated with the University of London. Paxton would be earning college credits, whereas I was taking spring semester abroad. We shared a creative writing class. Bill was amazingly entertaining, acting out his stories with his whole body, playing all the parts, like they were movies. The teacher teased him about his hyperbole, reliance on cliches, and overuse of profanity. Bill was a sport about it, quite willing to laugh at himself, which was endearing.

Unfortunately, whatever ambitions Bill had about writing may have been nipped in the bud at Richmond. He faired better in classes on Shakespeare and art history. He’d studied dramatic arts at Heights with legendary drama teacher Rosemary Burton. And there wasn’t anything he didn’t know about art, due to his upbringing. Bill’s father, John Paxton, was the vice president of sales for the family’s high-end lumber company. He traveled the world meeting clients and indulging in his favorite hobby: art collecting.

John, or JL, as his friends called him, deplored the intellectualization of art and admonished his four children to ignore the opinions of critics and develop their own taste through direct experience. When he brought a new picture home, he’d ask friends and family how they liked it. Abstract works could be confounding, prompting questions about the artist’s intention, the meaning of a piece.

“Hell, I don’t analyze it,” John would say. “I just enjoy it.”

Bill got the message loud and clear. By 1973 he had identified three of his favorite film directors: Clint Eastwood, Buster Keaton, and Hal Ashby. I preferred the Europeans: Truffaut, Bergman, Fellini, and others. Both of us admired the films of Stanley Kubrick, especially A Clockwork Orange.

Paxton could do a masterful impression of Malcolm McDowell as the sociopathic Alex. The first film we saw together was O Lucky Man, also starring McDowell, which provided Paxton with his theme song, a mantra almost:

Smile while you’re makin’ it.

Laugh while you’re taking it.

Even though you’re faking it,

Nobody’s gonna know.

Back in Fort Worth in the autumn of ’73, we conceived our first project together, “Victory at Auschwitz,” to help a schoolmate of mine fulfill a history assignment.

Bill and I wrote the story about an American commando behind enemy lines attempting to rescue POWs while they’re being transferred from one train to another. We cast ourselves among the POWs, and our friends played the Nazis and the hero. We would shoot with black-and-white stock to make it look like an old newsreel. The wardrobe and props, including weapons and a large Nazi banner, were authentic souvenirs brought home by our fathers from World War II. The location was a favorite haunt of Paxton’s: the municipal train yard off Vickery Boulevard. No one bothered to check the weather forecast.

It rained hard on the morning of October 14, 1973, endangering the camera but providing good production value. A couple of hours later, we were interrupted by the arrival of seven police cars, 14 cops, guns drawn, demanding we drop our weapons.

They’d gotten reports of a neo-Nazi uprising at the train yard.

Believe it or not, Paxton charmed the cops and the bosses at the depot into letting production proceed. The big scene left to shoot was Paxton’s attempted escape, which required him to perform a major stunt. He banged himself up pretty good.

Most of Bill’s ideas back then were about him doing something really dangerous and me filming it.

Next we pooled our savings, purchased Super 8 Kodak Ektasound equipment, and started cranking out films. Our magnum opus was “The Parable” starring Danny Martin, our third Musketeer, who had been with us on the trip to England. Bill was mostly behind the camera with me co-directing.

The story, by Paxton and Martin, was about a young loner unduly influenced by Clint Eastwood movies. After seeing Magnum Force — tagline: “A man has to know his limitations” — on the big screen, he buys a couple of guns and boxes of ammo, then builds a pair of dummies, intending to “murder” them in the woods. One of the dummies escapes.

The hero, who is really the villain, magically transforms into Eastwood’s spaghetti-Western character and tracks the poor dummy to an abandoned shack, where it doesn’t end well for the dummy. Tagline: “A dummy has to know his limitations.”

“The Parable” premiered in downtown Fort Worth at Daddio’s Bar and Grill. Paxton knew the owner, Nick Kithas, and talked him into letting us show our movie on a Friday night. Having not seen it in advance, Kithas was outraged by the level of gratuitous violence and gore. Regardless, “The Parable” won third place in a film festival sponsored by the Brooklyn Academy of Creative Arts, where one juror called it a “mini-masterpiece.”

This is when John Paxton noticed that his rowdy second-born son had an interest in something besides getting high, chasing girls, and wrecking cars. He booked a one-way ticket for Bill to Los Angeles and wrote letters of introduction to his Hollywood contacts, including big-time producer Hal Wallis, whom John had charmed while supplying exotic wood for the mogul’s office.

Bill asked me to go with him, but I was still in high school.

“Don’t go to L.A.,” I begged him. “Stay here, and we’ll start a Texas film industry, making films the way we want to make them.”

Paxton laughed. “Are you nuts?” he said. “I’ve been dreaming about this all my life. And my old man’s paying for it.”

Seeing the disappointment on my face, he tried to soften the blow: “Don’t worry, Tom, buddy,” he said, “I’ll pave the way for both of us.”

Maybe it goes without saying, but a close collaborator is like a soul mate or spouse. They are hard to come by. And besides, I had become dependent on Bill in many ways: co-dependent, I know now.

Arriving in L.A. in the spring of 1974, Paxton left multiple messages for Hal Wallis but never heard back. He rang the next name on his dad’s list, Milan Herzog, head of media production at Encyclopedia Britannica. Herzog hired Paxton and assigned him to work under staff producer Kent Smith, who had been doing everything literally by himself up to this point: writing, directing, editing, art direction, photography, scoring, you name it. Smith, a UCLA film graduate, spent his spare time writing feature-length scripts for European-style art films, which he hoped to direct.

Kent, intellectual, cultured, and bisexual, won the lottery with Bill. Not only was he the hardest worker he’d ever known, he was an experienced filmmaker and cineaste with impeccable taste and resourcefulness. He may have been fresh off the hay wagon from Hicksville, but he was hip, sophisticated, well-traveled, socially intelligent, funny, and sexy as hell. And he had a rich daddy. Smith had not only gained an assistant, he had a partner, muse, and potential money source. He saw Bill as a young Warren Beatty, a potential player who was game for anything. Conversely, Bill recognized Kent’s myriad talents and longing to leave his job and make real movies that mattered. The two talked of doing big things together, conquering the art house world, storming heaven. Their first move in this direction was an explicit, autoerotic portrait of Paxton, shot in black-and-white 16mm, called D’Artangan, patterned after Andy Warhol’s Factory films, meant to take the art world by storm. It was never finished.

Next, Smith wrote a full-length screenplay tailored for Paxton to star in and co-produce loosely based on the ill-fated J. Paul Getty kidnapping of 1973.

In 2016, Paxton spoke to a reporter from Variety about the making of Taking Tiger Mountain: “I was 19, and Kent was 31. We had the idea to make a film like Orson Welles’ version of The Stranger by Camus, only set in Morocco. We rented 35mm Techniscope equipment and purchased all the short ends [unexposed raw stock] from Bob Fosse’s Lenny, then flew to Spain. We rode the ferry across to Tangiers at midnight, whereupon our equipment was impounded, because we hadn’t made arrangements with the authorities in advance and didn’t know about baksheesh” or institutionalized bribery.

While Smith negotiated their extrication from Morocco, Paxton narrowly escaped arrest for possession of hashish. They ended up back in Spain, chewing each other’s ass when Bill remembered he had good friends in a remote area of Great Britain.

“Things got crazy when we got to Wales,” Paxton told Variety. Nearly the entire town of Llandovery came out to greet them. Crew positions filled immediately. Casting took place at a local pub. Much of the script was jettisoned, new scenes written. Bill became the co-director, line producer, and production designer. Smith concentrated on cinematography and trying to make sense of it all story-wise.

“One guy,” Paxton said, “had a trained Kenyan vulture, so we wrote a dream sequence where it ate my entrails. … I met a couple of girls and talked them into doing loves scenes. We were a bunch of hippies running around naked” –– and trying to make a masterpiece out of whole cloth.

Within a few weeks they had used up all the film and money. They couldn’t even afford to leave. A desperate telegram to John Paxton resulted in a loan of $5,000.

Upon returning to L.A. from Wales, Smith went back to work at E.B. Paxton reunited with Danny Martin, and they found work at Roger Corman’s New World Pictures with production designer Jack Fisk, husband of Sissy Spacek. Fisk and Spacek had just finished working with Terrence Malick on Badlands, a touchstone for fledgling auteurs until this day. Paxton waxed eloquently about it in an interview with The Telegraph.

I graduated from high school in May 1974 and moved to L.A. in late August, rooming with Bill and Danny, visiting Paxton on the set of Jonathan Demme’s Crazy Mama. Within days, we were shooting “Death Wish in Venice,” starring myself and Jac McAnelly, the costume designer from Crazy Mama. Bill operated camera. We shared directing duties as was our habit.

Within weeks, however, Paxton and Martin were tapped by Jack Fisk to work on Brian De Palma’s Obsession, written by Paul Schrader, ready to go in New Orleans. They barely had time to wave goodbye as they flew back to Fort Worth for some brief R&R. I moved in with Kent Smith and got to see all 10 hours of Tiger Mountain dailies, which was a lot more interesting than Bill had made it out to be, full of atmosphere, well photographed, lots of sex and violence, attractive performers, all in wide screen and black and white. It had the potential to be exactly what they had intended: a controversial European-style art film, potential cult classic a la El Topo, Alphaville, or Harold and Maud.

Paxton never made it to New Orleans. He got busted with drugs crossing the Mexican border and spent the spring of 1975 at home with his parents in Fort Worth hassling with the criminal justice system. At the same time he partnered with Charles and Richard Holder to make “Earth Army on Venus,” written by Charles, which Bill shot and directed.

“Bill had a specific vision for every shot and would not compromise,” Holder said. “He knew all the best places to shoot in Fort Worth and where to go to get anything we needed. … We didn’t pay for anything except film.”

Just after wrapping “Earth Army,” Paxton got a call from Fisk, who was back in L.A. and needing help finding locations for dePalma’s Carrie. It’s a testament to how highly Fisk regarded Paxton that he hired him again even after he failed to report for duty on Obsession. Although uncredited, Bill found the slaughterhouse featured in Carrie, where Nancy Allen and John Travolta collected the bucket of pig’s blood.

In the summer of 1975, Danny Martin and I were burned out on L.A. We applied at the University of Texas and got accepted. I handed my job off to Rocky Schenck. We had a few weeks to kill, so Bill, Danny, and I drove up the Pacific Coast Highway to see friends in Bend, Oregon. We filmed it all and called the result Peer Group Pressure.

The best thing I did before kissing Hollywood goodbye was introduce Bill to Rocky Schenck, auteur peas in a pod if there ever were any.

Their first effort, The Egyptian Princess: An Unfolding Fantasy, brought out the best in both of them. If I had another 2,000 words, I would wiseacre about this startling masterpiece of amateur auteurism and try to break down the relative contributions of Paxton and Schenck. But why don’t you just go to YouTube and watch it.

Also, in 1975 Bill made the acquaintance of Seymour Stein, co-founder of Sire Records, who discovered The Ramones, Talking Heads, and Madonna. They became fast friends, and Seymour would play a major part in at least three of Bill’s most important works as an auteur.

In 1979, two years after Bill had abandoned Hollywood for acting school at NYU, Egyptian Princess won the top cash prize ($10,000) in the world for a short film from the American Film Institute. Due to an unfortunate series of events, it did little to boost the careers of its makers. It is an affront to popular culture that it has never been transferred to digital, a fact I hope to help reverse in the near future.

In 1979, during my last year of film school, I acquired from Kent Smith all of the footage from Taking Tiger and D’Artgnan, raised money to finish it, did a page one rewrite, added dialogue, music, and sound effects, and shot a wrap-around sequence that explained why the rest of the movie didn’t make a lot of sense.

The high point of Tiger Mountain’s limited distribution was the sold-out world premiere at the Roxy in San Francisco, where Bill was treated as a movie star. The film received a handful of positive reviews, most notably from San Francisco’s grande dame of critics, Judy Stone. Never before available on video, it will be released early next year in a refurbished, remixed, and remastered hi-def letterbox version by Vinegar Syndrome.

By 1980, Bill had moved back to L.A., where he re-teamed with Rocky to make “Fish Heads,” a music video for Billy Mumy’s band, Barnes and Barnes. Directed by Paxton, it played twice on Saturday Night Live and holds the distinction of being named No. 57 on Rolling Stone’s list of the 100 best videos of all time.

On the set of Streets of Fire in 1983, Paxton met Andrew Todd, a master musician and songwriter who had just disbanded his group Martini Ranch.

Paxton, who was augmenting his acting career delivering newspapers at 3 a.m. often wondered if he should not try his hand in music, as he worshiped and wished to emulate Jim Morrison as much as Buster Keaton.

Todd and Paxton reformed Martini Ranch as a production company and video band, which was the new rage due to MTV.

Seymour Stein funded the recording of a demo of their song “How Can the Laboring Man Find Time for Self Culture?” produced by Devo’s Bob Casale. Paxton tapped Schenck to direct the video, which knocked the socks off everybody who saw it and won them an album deal with Sire.

The first single off Martin Ranch’s LP would be “Reach.” Like “Laboring Man,” it was an upbeat techno dance tune. The lyrics were a throwback to the cowboy novelty songs of Frankie Laine and the spaghetti-Western scores of Ennio Morricone, telling the story of a bankrobbing fugitive on the run in the Old West.

Bill approached me about co-producing the video and using ideas from a script we’d written together, Lonesome Cowgirls: Amazons of the Wild West, a militant-feminist Western set in 1869 in the Black Hills of Dakota. Then he asked James Cameron, his close friend and long-time associate, to direct it. Cameron said yes and would do it for free, as long as he and Bill would have creative control. It was Cameron’s idea to set the story in a dystopian future.

“For ‘Reach,’ … Bill called in more favors than I’ve ever seen called in on one project,” Cameron said.

Bill tapped Kathryn Bigelow, the director of Near Dark, to be the leader of the all-female band of bounty hunters pursuing a devil-may-care fugitive (Paxton) through the desert, backed up by Jenette Goldstein (Aliens, Near Dark) and five more badass babes. On the testosterone side, Bill roped in Lance Henriksen, Mark Rolston, Adrian Pasdar, Paul Reiser, Bud Cort, Judge Reinhold, and Lewis Abernathy –– and placed them all in a giant set built by Walter Hill for Extreme Prejudice at the Veluzat Motion Picture Ranch.

We shot the hell out of the place for two days in the blistering heat of August 30 and 31, 1987, with three jet engines stirring up dust for atmosphere and with everyone in full cowboy drag.

Cameron wrote, “I’ve never felt more free or imaginative on set. … I can hardly think of Bill without thinking of ‘Reach,’ how, in so many ways it is a time capsule of his life … just about everybody he knew and loved surrounding him and giving them everything they had.”

“Reach” is a feature film in miniature, with a coherent narrative structure, three-dimensional characters, central conflict, and universal themes.

Earlier this year, as a tribute to Paxton, Cameron’s production company, Lightstorm Entertainment, spent a couple of weeks remastering the 35mm negative to 4K, adding head titles and end credits.

This new version of “Reach” will screen at 8 p.m. on Saturday at Four Day Weekend Theater as part of the film festival along with Traveller, Paxton’s 1997 drama with costar Mark Wahlberg.

“It was the most fun I ever had making a movie. “Cameron said.

Bill sank $45,000 of his own money into “Reach,” firmly believing that Warner Bros. Records would be so blown away by the video that they would reimburse him. Instead, they dropped the band and did not promote the album.

Bill’s fantasy of rock ’n’ roll stardom was dashed. He returned to his day job, acting, with a vengeance. He also left L.A. with his new bride Louise for Ojai, an hour north of L.A., bought a fixer upper, and started planning a family. He also fired his agency and hired a new manager.

Eight years went by before he could think about making another movie. During this time, he appeared in 25 films, including Brain Dead, The Dark Backward, One False Move, Indian Summer, Tombstone, True Lies, Apollo 13, and Twister. He developed a keen eye for good writing. He learned the hard way that you can’t make a great movie from a mediocre script no matter how much effort you put in. The play’s the thing.

When Tom Hanks turned down the lead in Twister, he recommended Bill. It was a dream come true to star in a Steven Spielberg production, but the script was so weak it offended his sense of aesthetics. He hired me as his personal script doctor.

Despite our efforts and the efforts of some of the biggest writers in Hollywood (all uncredited), the script barely improved by the start date. Director Jan De Bont, formerly a top DP who came up with Dutch auteur Paul Vehoeven, had little background in storytelling.

Twister was also plagued in production. The original camera crew quit in disgust with De Bont. Jack Green, a San Francisco-based DP and protege of Clint Eastwood’s, took over. Bill bonded immediately with Jack, who did a great job until a set collapsed on his head, forcing him into the hospital, whereupon De Bont finished shooting the picture himself. Bill predicted Twister would be a commercial hit for its dazzling visuals but for no other reason.

So what do you do when you’re a total filmmaker with good taste and the ambition and chops to make great cinematic art, but you’re also a cog in the Hollywood machine with a family to support? You find a good script and buy an option on it.

Travaler was a spec script by a first timer, journalist Jim McGlynn, who won the highly prestigious Nichols Fellowship Award, administered by the MPAA in 1989. Bill wanted to star in it and control it but didn’t feel ready to direct. He offered it to Jack Green, who was aching to direct, if he would shoot it, too.

The resulting film (retitled Traveller by Paxton to reflect the Anglo-Saxon origins of his character), starring Paxton, Mark Wahlberg, and Julianna Margulies, won two thumbs up from Siskel and Ebert, noting that Paxton the producer had given himself one of the best roles of his career. Many critics agreed. Nobody knew he also had final cut.

Also, Traveller was the first film in which Bill was partnered with David Blocker, who went on to produce all of Bill’s films he directed. He was Bill’s feature film partner as an auteur and he will be co-hosting the Fort Worth screenings.

Seymour Stein contributed significantly to Traveller, personally overseeing the soundtrack, picking 22 public domain songs to be recorded by 12 artists he was associated with, including Randy Travis, kd lang, Jimmy Dale Gilmore, and Mandy Barnett. Kyle Leaning and Andy Paley produced the tracks and Paley composed the score.

That is another hallmark of the films Bill produced or directed: boosting the careers of maestros like Brian Tyler, who scored Frailty and The Greatest Game Ever Played.

Due to Jack Green’s association with Frailty, Bill finally got to meet Clint Eastwood, who admired the film. The Sundance Film Festival passed on it, but SXSW, building its reputation as a film festival, booked it as its opening-night feature. Bill’s fellow Texas auteurs Richard Linklater, Robert Rodriguez, and Mike Judge were impressed. Bill felt like he was finally being reevaluated in the right way. (Later the Sundance Channel played it under the rubric Movies We Love.)

As I had been helpful in post-production as the music supervisor and editing consultant, it reminded Bill of how well we worked together, that he could trust me to give my opinion and fill in when he was gone.

A year later, when Paxton established his own company, American Entertainment, he hired me to be head of development. My job was to find more scripts like Traveller that he could star in and produce.

Within a year, we had set up projects at Disney, Universal, HBO, and Sony in partnership with Ron Howard, Ron Shelton, Jonathan Mostow, Jon Tultetaub, and Robert Zemeckis.

During this time, Gus Gustaves, running Matthew McConaughey’s company at the time, approached me about slipping a pet project of his to Bill, which he called “a fantastic script by an un-produced writer from Irving, Texas.”

I read it late that night. It unnerved me so that I got up at least a couple of times to make sure the doors and windows were locked.

Bill agreed that Frailty was brilliant, reminding him of two of his favorite films, The Night of the Hunter and To Kill a Mockingbird, before he added, “But there is no way I will play that part.”

Why not?

“I’m not going to play a guy who abuses his kids,” he said. “I have two young children.”

A few months later, Bill woke up in the middle of the night, thinking about Frailty. He decided if he could direct it, control it, he would take the part.

I gave producer David Kirschner the news: “Bill will play the dad –– if he can direct it.” There was a long pause on the other end.

David, inventor of Fievel the Mouse and Chucky the Killer Doll, didn’t know much about Bill. He was just that guy from Twister, Aliens, and Weird Science, whom the writer had in mind when he wrote the part. He agreed that Bill was perfect to play the dad. He could use Bill’s good old boy carriage and smile, his mainstream appeal, to guild the awful lily of the character. But could Paxton direct?

It took only one meeting with Bill to convince him. “He came in with a satchel full of paintings, story boards,” Kirschner said. “I was blown away by his preparation and his passion.”

The rest fell together pretty quickly: David Blocker as line producer, and Bill’s pals Matthew McConaughey, Luke Askew, Powers Boothe, and Vincent Chase grabbing the other great parts without having to audition.

The result put Bill on the A List of Hollywood directors and blew away the critics. Roger Ebert wrote, “Frailty is an extraordinary work, concealing in its depths not only unexpected story turns but implications, hidden at first, that make it even deeper and more sad.”

Next up for him as a director was the film that would, unfortunately, be his last. The Greatest Game Ever Played was written by Mark Frost from his nonfiction book of the same name.

“I have never worked with a director who was more committed to getting every single detail exactly right,” said Frost, who became dear friends with Paxton. “He was brilliant with actors. He was brilliant with crew, and his energy was unflagging,”

Blocker said, “He was a true artist in the best sense of the word. His life was dedicated to art. He brought to everything he did a ferocious commitment to rooting out the truth.”

Let’s give Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers the last word on Bill. In his memoriam, he wrote, “Bill wasn’t finished –– not as a husband, father, friend, actor, filmmaker, and citizen of the world. The best tribute we can pay him as a talent is to watch a few of the films that mattered most to him; they paint a fuller picture of what he reached for and what he so gloriously achieved.”

Photo by Jeff Prince.

Just before press time, the Fort Worth Weekly staff and I learned of the sudden passing of Johnny Langdon, long-time chairman of the board of the Lone Star Film Society. Having once worked under Johnny myself, I knew him to be a dedicated, vocal supporter of local artists, who put his money where his mouth was. We offer our heartfelt condolences to his wife and children.

Bravo, Tom.

Good read. FAN!

Fascinating stuff; many thanks!

It reads much like Bill lived. Well done. And incredibly informative. Danny told me maybe half of what you wrote. It explains a part of their bond that was strong and deep. Thanks for doing this.