Susan and Jenny fought earlier that night. It was nothing unusual for this mother and 16-year-old daughter. But that Tuesday in July of 2015 was different. Words were spoken that would not be easily forgotten. Jen, which is what Susan had called her for years, had stormed off to her room, slamming the door with an anger that Susan had not seen before. Susan knew Jen’s friends meant more to her at this point than she did. Jen was in continual contact with them via her phone and laptop. She wanted to go out, but Susan told her no, she was to stay home that night.

A tall, thin, stunningly beautiful girl, Jen was sure she was overweight and that her classmates were out to get her. Earlier in the summer, Susan had engaged the help of both a psychiatrist and a therapist, and she was having Jen randomly drug tested. But the daughter continued her defiant behavior — stealing money, not sticking to curfew, and sneaking out of her bedroom at night. Their relationship became even rockier as the summer wore to a close.

School started. Jen was bright and had earned good grades up until that year. But calls from the school began and were becoming more frequent, not just about her skipping days but also about her behavior when she was in attendance. Susan was sure she was using drugs. One morning that fall, Jen walked out of her room carrying a bag and announced she was moving in with her girlfriend. After another draining argument, Susan relented and agreed she could go. Susan knew the friend, Alisa, and also knew her mother, and she knew where they lived and how to reach them. Susan told Jen she would not turn her phone off as long as Jen answered her calls and texts within a reasonable amount of time.

Susan, divorced and a single mom for years, was also the mother of a 26-year-old daughter who had already married and moved out. Susan, always passionate about her girls, would much rather go to a movie with them or have their friends over than go out with her own friends. She had recently left a career as an executive to be home more for her younger daughter during her teenage years. Her current position allowed her to work from home and have more control over her schedule — but now her youngest was gone, at least for a while, probably until she was tired of Alisa and her family. It all went well for a few days. Jen was returning calls and responding to texts. But then something happened.

Susan had an app on her phone that allowed her to track Jen’s location. She set an alert for 9 a.m. and 10 p.m. daily to track her in school in the morning and at Alisa’s home at night. Two weeks after Jen moved out, Susan’s GPS pinpointed her daughter at a location she did not recognize. Again, the next evening, the same location appeared. It looked like it might be a hotel. Susan called her daughter. Jen said her friends had pooled together some money to celebrate her birthday. They just wanted to get away for a few nights, Jen said. Susan decided she was worrying too much.

A few days later, Jen, with Alisa and another friend, met Susan and Jen’s older sister for a birthday lunch. Susan probed her younger daughter again.

“Where were you those nights you weren’t at Alisa’s?”

The other girls vouched for Jen. It was just a weekend outing for a birthday celebration. The next week the school started calling again, saying Jen was absent. Another GPS search that evening brought up the same cryptic location. Susan called her daughter, but instead of returning her mother’s call, Jen started replying via text: “My battery is dying. I can’t stay on my phone.”

That’s when Susan went to Jen’s detailed phone log. A number appeared more than 50 times with calls that never lasted longer than a few minutes, including incoming and outgoing. Susan searched Facebook but no match. A Google search brought back the usual — Whitepages.com, Callername.com — but farther down the screen, there it was: Evilempire.com. At first Susan thought it was a video game. It was primarily black, but it had the typical search cue with a magnifying lens. Susan pasted the same phone number into the search engine. A picture appeared. There she was, a young girl, in a thong, bent over a bed, the picture taken from the back so all you could see was her rear. An arrow pointing to the right of the screen read, “Click here for more photos.” There was Susan’s little girl, almost nude, on a hotel bed — the pictures out there for eternity.

Susan spent the next five hours trying to find someone to tell her what to do. Phone call after phone call — some transferred her, some told her to file a police report, and one agency representative in Austin said she was sorry and hung up. The Fort Worth police department sent an officer out to speak with her. Susan waited, angry, crying, embarrassed, hurt, but, more than anything, afraid. The policeman connected Susan with the lone detective who worked sex trafficking in Fort Worth.

“Do nothing,” he told her. “Wait, watch, and try to get her to come home.”

Susan had a hard time with this.

“Every ounce of my body wanted to run to that hotel and drag her out of there,” Susan told me in an interview later. But the detective convinced her that that would result in one of three outcomes: Jen would be murdered, Jen and Susan would be murdered, or Jen would totally disappear, possibly never to be found. For the next two long weeks, when Susan talked to Jen, she said nothing out of the ordinary.

Then one day, Jen came home. According to what little she said, the pimps were talking about moving her to another city because “her mother keeps calling.” That awakened a spark in Jen. She found a time when she was alone in the hotel room. She picked up what few belongings she had and ran barefoot to a nearby IHOP restaurant and called a friend to come pick her up.

The detective advised Susan to say little: “Wait until she is ready to talk.”

During Jen’s first conversation with the detective and an agent from the Department of Homeland Security, she spoke only of the man who raped her, pushed her out of a moving car, burned her with cigarettes, and threatened her family. She said the others were nice to her and had tried to protect her from the bad one.

During Jen’s first conversation with the detective and an agent from the Department of Homeland Security, she spoke only of the man who raped her, pushed her out of a moving car, burned her with cigarettes, and threatened her family. She said the others were nice to her and had tried to protect her from the bad one.

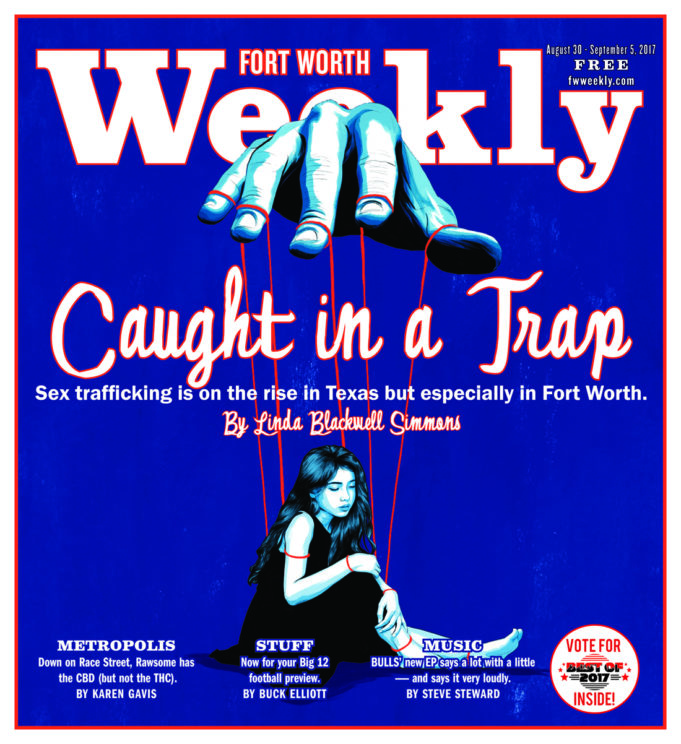

Having recently read a short clip in the local paper about sex trafficking in Fort Worth, I decided I wanted to learn more. Perhaps there was a story there. On a warm Tuesday morning earlier this summer, I drove to a police substation in East Fort Worth. That’s when I was introduced to the Tarrant County 5-Stones Taskforce. Before my first meeting, I expected maybe a handful of attendees. I was surprised to walk into a room with about 75 people, some in suits, some in shorts.

That meeting was also when I first met Susan. We were in a breakout session together and ended up sitting by each other. At first I thought she was a volunteer assisting victims. She quickly set me straight. Susan is educated and well spoken, and she brought a presence to the room. She lives in Fort Worth, lives and raises her girls in an upper middle-class home, has a nice car, and has a dog and a cat. She is, in all respects, normal. She’s not who you would expect to be the mother of a sex trafficking survivor.

Susan, too, was a little apprehensive at her first taskforce meeting.

“When I first attended back in January,” she said, “I felt vulnerable, but when I walked into the room, I saw familiar faces. One of the [Homeland Security] agents who had worked with my daughter and me waved me to an open space next to her. There were about 40, 50 people in the room. As I walked to my seat, I found myself wondering where were all these people the day I needed them the most? We were all asked to introduce ourselves and say why we were attending. My heart leapt, and my fear and anxiety rose as the individuals began introducing themselves one by one. What was I going to say? How would I explain why I was there? When my turn came, I took a deep breath. I stood, said my name and that I was the mother of a survivor. My voice quavered, and tears ran down my face. What only took a moment seemed like an eternity and took all my strength to do. I sat quickly, and the person next to me handed me a napkin. There was a moment of silence in the room, and then the process continued. I had crossed a major milestone in my own recovery and taken my first step toward becoming an advocate.”

The taskforce was partly the brainchild of Fort Worth police’s Felicia Grantham. In 2014, she met with former chief Jeff Halstead to ask permission to work with other peace officers throughout Tarrant County to respond to minor sex trafficking. Interest grew, she said, until the group was formalized in January 2016. The taskforce is now an arm of Fort Worth police and is represented by approximately 45 agencies. The public is welcome to attend the taskforce’s monthly meetings (last Tuesdays).

Grantham told me their focus is on cost-effective strategies, identifying youth at risk, “which is crucial to prevention,” providing community education, and increasing the accountability of those on the demand side, the johns and pimps.

“Kidnapping a victim does happen, but trafficking is so much larger than this,” Grantham said. “People need to realize that trafficking is happening right here in our neighborhoods and that a runaway youth is not just a deviant child or one who chooses to prostitute. Trafficking is an equal-opportunity employer. In my experience, the majority of victims are tricked into the initial situation. Certain factors do make one more susceptible, such as being young, being homeless or transient, having a history of physical or sexual abuse, being a runaway, existing in the foster care system, or having a parent who has problems with either drug/alcohol abuse or domestic violence. Many at risk youth like having a new boyfriend or at least someone willing to take care of them in some way. After trust is built, then the trafficker begins to turn the tables.”

The victim is usually unaware of her reality and can be trapped quickly, she said.

“She may prostitute once or engage in one pornographic session at the request of her ‘boyfriend,’ and now this is held over her, so her shame keeps her from leaving, and the trafficker now requires her to do more,” Grantham continued. “She may believe her ‘boyfriend’ really loves her, and she may feel this is just her role in the ‘family.’ Many times, the trafficker will get the girl addicted to drugs, and this will help keep her in the cycle.”

Homeland Security defines human trafficking as “modern-day slavery and involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act.”

Sex trafficking is one type of human trafficking. Human trafficking also includes coersion into labor.

Fort Worth saw its first large case in 2002, said Hannah Rivard with Fort Worth police’s Major Case Unit, but there’s been a “significant spike” in the last five years. From 2013 to 2016, the Polywood Crips operated a sex trafficking ring on the East Side near the Polytechnic Heights neighborhood, near where the taskforce meets. “Pooh,” “Pee Wee,” “Spud,” “Spank,” and the rest of the street gang even trafficked a 16-year-old female runaway. The gang posted videos on Facebook which provided instructions on how to pimp. Nine suspects were recently convicted in federal court, some now serving up to 30 years in prison. Twenty-two victims were identified during the nine-month investigation.

Dallas/Fort Worth and Houston are the highest in the state for sex trafficking hotline calls, according to data presented to Fort Worth City Council in May by Assistant Chief Kenneth Dean. Cases in Fort Worth are surging: 26 already from January through April, compared to 28 in all of 2016. Greater community awareness and more resources focused on sex trafficking partly explain the increase, according to Grantham.

Executive director of UnBound Fort Worth, a nonprofit devoted to fighting human/sex trafficking, Stephanie Byrd knows Fort Worth is not immune to the crime.

“Human trafficking is happening right here in our community,” she told me. “I know because I have personally spent time with survivors. I have sat and listened to their stories. It’s not generally the case that a girl is walking across a dark parking lot, and a truck comes along and swoops her up. Much more commonly, a youth, often with unmet physical or emotional needs, is tricked into trafficking by someone who pretends to care about her. A new ‘boyfriend’ may invite a young teen to move in with him. Perhaps after several weeks or even months, after he develops a high level of trust with her, he will suggest she have sex with someone to help with the rent. And it goes from there, often involving violence and threats against her or her family if she tries to leave.”

It’s not unusual that within 48 hours of being on the street, a youth will be approached by a sex trafficker. Trafficking victims may be any age, race, or economic status. They come from good neighborhoods as well as disadvantaged areas. In a 2016 study, the University of Texas reported that more than 300,000 victims of human/sex trafficking were living in Texas, including nearly 79,000 minors and youths.

It’s not unusual that within 48 hours of being on the street, a youth will be approached by a sex trafficker. Trafficking victims may be any age, race, or economic status. They come from good neighborhoods as well as disadvantaged areas. In a 2016 study, the University of Texas reported that more than 300,000 victims of human/sex trafficking were living in Texas, including nearly 79,000 minors and youths.

It was a Saturday night in October, early in the school year, and Megan had no homework. Her mom was angry with her, but Megan didn’t remember why. In her room, bored, she began trawling the web on her laptop. Then something caught her eye. She logged on. It was a dating site. A few nights later, she logged on again and made contact with a handsome young man, maybe not much older than she. Careful not to tell him her address, she agreed to meet him that next weekend at a local fast food restaurant. Before long, he convinced her that all of her problems would disappear if she would only move in with him. She did.

“He was nice at first,” Megan told me later. (Like most of my other sources, “Megan” is a pseudonym to protect her privacy.) “I wanted money so I could go and do what I wanted. I didn’t know I was being trafficked until he wouldn’t let me go.”

A typical day for Megan consisted of answering calls, having sex, smoking, eating, sometimes taking showers, and sleeping when she could.

“But I got smarter,” she said. “One day, a light bulb went off in my head. I was sitting there. He left the room because he got mad and was gone for a while. I suddenly thought ‘run.’ I had money in my hand that he hadn’t taken. I’d made $500 that day. I took a trash bag, put my clothes and soap and stuff in it, and ran for the stairs. I was so scared he would come back and catch me.”

Megan’s case is not uncommon to Traffick911, a Texas nonprofit that battles against sex trafficking.

“The truth is there is a very real sex trafficking problem in Fort Worth,” said Lindsey Speed, director of programs. “Our agency has worked more than 50 cases in the last five years — most of them teenage girls. We work with the Fort Worth police on a regular basis.”

Speed recommended I check the dating subhead on Fortworth.backpage.com.

“Statistics and our own experience show that a large number of the younger girls posted on sites like Backpage are being trafficked and controlled,” Speed said. “The ads will say the girl is over 18, but that is not always the case.”

Letters from young survivors are posted on Traffick911.com. “I learned that the pimp has no face,” one writes. “They are never who they seem to be.”

Vanessa Bouche, assistant professor of political science at TCU, is currently working on three federally funded grants on sex trafficking. In one particular study, she partnered with 20 other service providers across the country to survey former victims from January 2016 to January 2017. Of the 300-plus survivors she interviewed, 82 percent entered into sex slavery when they were 17 or younger. The average age was 14.78, while the average age of the trafficker was 28.8. Her findings agree with other research.

“Girls can be recruited at school, through a mutual friend, over the internet, or groomed in their own homes through sexual abuse by a family member,” Bouche told me. “Many times, the girls develop a relationship with the trafficker. He makes them feel loved, perhaps for the first time in their life.”

At 3 p.m. one weekday afternoon, Bouche asked her students to set up a fake Backpage ad that solicited men to meet a girl at an apartment on University Drive near campus. At 7 p.m., the students went to a coffee shop directly across the street to observe. As each man arrived, a student called him and pretended to be someone from the ad. The students asked the “buyers” to do outrageous things to prove they were who they said they were. In one instance, a student asked a “buyer” to buy her a cup of coffee at the very shop where the students were sitting, which he did. In another, the “buyer” was told the girl had her 4-year-old son with her. “That’s OK,” the man said. “He can stay.” In the amount of time the ad was set up to the observation time, a girl could have had sex with nine different men.

Kelley O’Conan, project manager of Children at Risk, said some girls as young as 11 are being trafficked. She once worked in Fort Worth’s homeless district, where she said she saw many young people trading “survival” sex for food and protection. Her worst experience, she said, was a Hispanic girl about 11 years old who lived with her family in a nice middle class home.

“She attended a good school, played with her friends on Saturday, and went to church with her family on Sunday,” O’Conan said. “All was well, except the ‘friends’ with whom she played on Saturdays were johns. The neighbor told her he would kill her family if she told anyone.”

There are male victims as well as female, gay as well as straight, and just as well there are female pimps.

All income brackets are vulnerable.

With help from the 5-Stones Taskforce, Children at Risk recently sponsored a bus tour.

The tourgoers were “shocked,” O’Conan said. “They were prepared to see the ‘underbelly,’ not downtown luxury hotels. It happens in every neighborhood — poor, middle, and rich. The normal case is not one of kidnapping as many people think. The girls are groomed and many times are found with Stockholm syndrome and defend the trafficker.”

Gov. Greg Abbott recently signed a law mandating training for truckers to help combat trafficking.

“We will be putting thousands of sets of eyes and ears out there to help in our efforts against this horrible epidemic,” said Sylvia Garcia, the Democratic senator from Houston who authored the legislation.

Under the new law, applicants for a commercial driver’s license will undergo training to identify signs of trafficking and how to report it.

Another bill recently passed mandating that victims’ addresses be removed from public records. Additionally, the 5-Stones Taskforce has partnered with Abbott’s office to develop long-term mentors who will assist in providing wrap-around care to high-risk youth and their families.

The trafficking saga often doesn’t end after rescue. The Refuge for DMST (Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking) is developing The Refuge Ranch, a long-term residential, therapeutic home for girls 11 to 17 years old who have been rescued out of sex trafficking. Slated to open later this year, the Refuge is located on 50 acres in a beautiful, restorative setting outside Austin. The facility will provide trauma-informed holistic care, including: a University of Texas Charter School program, a People’s Community Clinic, and various therapeutic programs uniquely designed for the development of a child survivor. Additionally, there are tentative plans to open a similar facility in or around Tarrant County in the near future.

The trafficking saga often doesn’t end after rescue. The Refuge for DMST (Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking) is developing The Refuge Ranch, a long-term residential, therapeutic home for girls 11 to 17 years old who have been rescued out of sex trafficking. Slated to open later this year, the Refuge is located on 50 acres in a beautiful, restorative setting outside Austin. The facility will provide trauma-informed holistic care, including: a University of Texas Charter School program, a People’s Community Clinic, and various therapeutic programs uniquely designed for the development of a child survivor. Additionally, there are tentative plans to open a similar facility in or around Tarrant County in the near future.

In Fort Worth, the police department recently added an officer “on loan” from another department, and trafficking was placed under the Major Case division. This allows the use of six major case detectives if the need arises — however, they handle a number of other high crimes, including kidnappings and officer-involved shootings, so they are not devoted to trafficking. The department also works with one or two Homeland Security agents, depending on need, along with the 5-Stones Taskforce.

Almost two years have passed since Susan made that first phone call seeking help for her daughter. Since that fall, Jen spent six months in rehabilitation for mental health issues and drug abuse. She testified in front of a grand jury, facing the family of the man who recruited her.

Wanting an update on both mom and daughter, I drove to a taskforce meeting on another warm Tuesday morning late this summer. Susan greeted me with a smile.

“I am now a volunteer with Traffick911,” she said, adding that she has almost completed her training to instruct young people how to recognize the trafficker’s traps and lures. Her first presentation will be this month at the high school Jen was attending when she was trafficked. Jen also has a job and is working toward becoming an official volunteer to begin advocacy work.

“It’s still a struggle to be in the same neighborhood,” Susan said. “Rumors run rampant, but Jen just enrolled in an accelerated program to earn her high school diploma by year end and seems dedicated to achieving this goal.”

Someone that day used the word “victim.” Susan turned to me.

“We’re not victims,” she said. “We’re survivors.”

Am I the only one who doesn’t understand how a mom let’s her teenage daughter go “live” with another family with no contact or discussion with the parents?

I really appreciated the article in Fort Worth Weekly about sex trafficking. I learned what to look out for in the future. Then I turned a few pages and on pages 40-41, the “Classifieds,” were at least a dozen ads for prostitutes and phone sex lines…If FT Weekly wants to help in the fight against sex trafficking, maybe they should start by not accepting money from/allowing ads from sex traffickers. Just a thought…

The fact that sex trafficking is increasing in Fort Worth indicates that the efforts made so far to root out this social crime have not worked out effectively. This sorry state of affairs calls for further efforts from all stakeholders — government, all sections of society, and every citizen — to be more alert and work towards the same end. Spreading more public education about the traps and pitfalls and how to avoid falling into them is also necessary, apart from the need to make laws and conditions more difficult for the traffickers and their agents. There are black sheep aplenty in every society, and any calls to duty, humanity and such noble feelings do not at all appeal to them. Only stern action can be an effective deterrent. The news piece was illuminating. Keep it up.

Sex trafficking is not only in Ftw. Sex trafficking is everywhere. Its just out in the open in Ftw. Anyplace big. A big city, then 90% if the time its happening there as well.

I can relate to this article. Thank you for writing this and sharing.

Law enforcement and the justice system is focusing on just some of the problem. They need to focus on the root of the problem. Then when they get a grasp on that then they will be able to handle this problem. As long as there is drugs readily and able to get and as long as families lack communication skills with their children then this is going to persist.