Leaving Texas recently to volunteer in Cape Town was an opportunity I couldn’t resist. Unsure what to expect, I googled images of the South African city and saw beautiful beaches, mountains, and ocean views – not exactly things that a native of flat and dry Fort Worth is used to seeing. Why would such a gorgeous place need volunteers for anything? Turns out, the entire country of South Africa suffers from a wide array of issues, including poverty, income inequality, and segregation. Add in a countrywide recession and a president with as many scandals as our own, and it’s easy to see why the residents are fed up.

I was there with One Heart Source, a nongovernmental organization whose members teach students math and writing after school. For me, this was a great chance to give back to society and travel abroad. While the locals’ angst could be seen everywhere, I struggled not to get sucked in by the city’s beauty. The mountains seemed to touch the clouds, and emerald ocean waves brushed up against white beaches. Not to mention my benefiting from the country’s 13-to-one dollar transfer. I ate lavishly every day. On my last night in Cape Town, I bought a round of 14 shots – for only about 14 bucks. That’s something I really missed the first time I bought food and drinks back home.

But all of that beauty (and those dollar shots) can be deceiving. In the local papers, I read of government corruption stretching all the way up to the president. Locals spoke of racism and classism. And I couldn’t get over seeing the students I mentored walking home from school unaccompanied down dirt roads to small, impoverished neighborhoods surrounded by luxurious homes and beaches filled with tourists. Some of the disappointing things I saw there mirrored, to a lesser degree, what I see at home.

Cape Town’s income inequality was obvious and clearly driven by race. As I was being driven up one of the huge oceanside mountains, the scenery changed drastically. Small makeshift shacks in overcrowded neighborhoods of mainly black residents quickly turned into expensive mansions secured by steel-reinforced concrete walls. Through the openings you could see white children playing in the yards. Not something I expected to see on a visit to Africa. It’s no wonder why World Bank said that South Africa was “the most unequal country in the world.”

*****

Everyone I spoke to in the city attributed this inequality to segregation from the apartheid era. Apartheid was the government-instituted system of racial segregation that dictated housing, employment, and social standing based on race, ethnicity, and tribal ancestry. The country’s ruling white minority imposed apartheid in 1948, and the wounds never quite healed. Many locals say they still feel its effects.

After a few days in the country, I met Peter Michaels, a 25-year-old local who grew up in Hout Bay, a small town just outside of Cape Town. He introduced himself as a kung fu-fighting rapper and photographer. I was a bit skeptical at first, but he wasn’t kidding. He was well known throughout the community. The fighter and trainer has represented his country in kung fu competitions in China, Hong Kong, and Indonesia. He raps throughout Hout Bay under the stage name Spike P. As a photographer, he also helps produce music videos for local artists.

“There is an inequality … in where the people are staying,” Michaels said. “It feels like apartheid is still going.”

Michaels said the neighborhoods are still segregated by the boundaries that apartheid created. During apartheid, many people were moved from their former homes and put into townships of their own race. The black residents were moved from the areas where they lived for generations and placed into townships made of steel shacks. Residents from other cultures who weren’t considered black or white South Africans were labeled as “colored” and placed into neighborhoods composed of small flats.

White residents, most of whom were better off financially, took the coastal or nicer areas closer to the city.

This explained why every direction I looked seemed as if I was in a completely different area. I could turn 360 degrees and think I was in three different parts of the world. But these neighborhoods weren’t separated by anything but air and concrete.

Michaels is from Hangberg, a small, “colored,” low-income neighborhood built on the side of a mountain that overlooks Hout Bay’s port and all of its tourist attractions. Extremely poor neighborhoods sit in close proximity to well-to-do areas throughout the city. I had seen this before in America but not to this extent.

Imizamo Yethu, also known by its abbreviation I.Y., manifested the most accurate portrait of the segregation and poverty. The area was an assortment of steel and wooden shacks. It was crowded. Children played unattended on every corner. I also saw starving stray dogs sleeping (I think) in the streets. And the streets were made of concrete, grass, and gravel, as if someone started to construct a road but gave up halfway through. Directly across the street, huge pictures of real estate agents hung on the sides of gated communities of primarily white residents.

As the black children of I.Y. kicked around soccer balls on the corner of their low-income shack townships, white residents passed by in Mercedes-Benzes. I wondered how the townsfolk living in these areas felt living among such socioeconomic extremes.

I asked Lelothando Bokuva, a 24-year-old who’s known to many as “Lelo” and who works as a youth chairperson for the local political party the Democratic Alliance (DA) and with One Heart Source. He said that although he is committed to bringing together his countrymen and -women, seeing his people live in these conditions does bother him.

“It does make me angry,” Lelo said. “We find a black person living in a shack, colored people in a flat, then white people living in these big mansions. How can we come together when we are so segregated?”

I couldn’t help but feel what the people in town were going through. Both the city and country seemed to be in constant distress. A recent fire burned down several homes a few months before I arrived, and the county was in a drought. When the rain finally came, it was in the form of a devastating storm. And not just any storm, either. It was one of the worst to hit the area in decades, according to many news sources. It struck the city on my fourth day – I was lucky to be in a safe place at the time. Locals, especially black and colored residents, weren’t as lucky. The next day, the local paper reported that the storm had caused eight deaths.

As bad as things seemed to be in the city, however, you wouldn’t know talking to the townsfolk. They were friendly, and everyone was quick to introduce him- or herself. Tourists coming the following weekend probably didn’t even know what had happened just days before. I guess it was hard to stay down with such beautiful sites all around. Folks living in some of the roughest areas were welcoming, friendly, and even dancing. And the music playing all around town – hints of Latin, hip-hop, and Caribbean but with a heavier use of drums and congos – was upbeat and unlike anything I had ever heard before.

But even celebrations in this country were reminders of its long history of struggle and its people’s fight for equality. Every June 16 is Youth Day, when schools are closed, and activities are held for children all over the country. These celebrations serve as a reminder of the Soweto Uprisings of 1976 – a string of protests for the basic rights we enjoy here in the United States.

The protests back then were led by students from the Soweto Township and spread quickly throughout the country. Under 1953’s Bantu Education Act, more recourse was given to white students over their black peers, who were forced to learn Afrikaans, a language introduced by Dutch settlers which was mainly used by the white ruling minority. Many black students preferred to be taught in English or their tribal language and saw Afrikaans as the voice of the oppressor. Fierce opposition from police and the government met the student protesters. The government-appointed Cillie Commission of Enquiry concluded that 575 people died over a three-day period, 451 of them due to police action. Several of the dead were children.

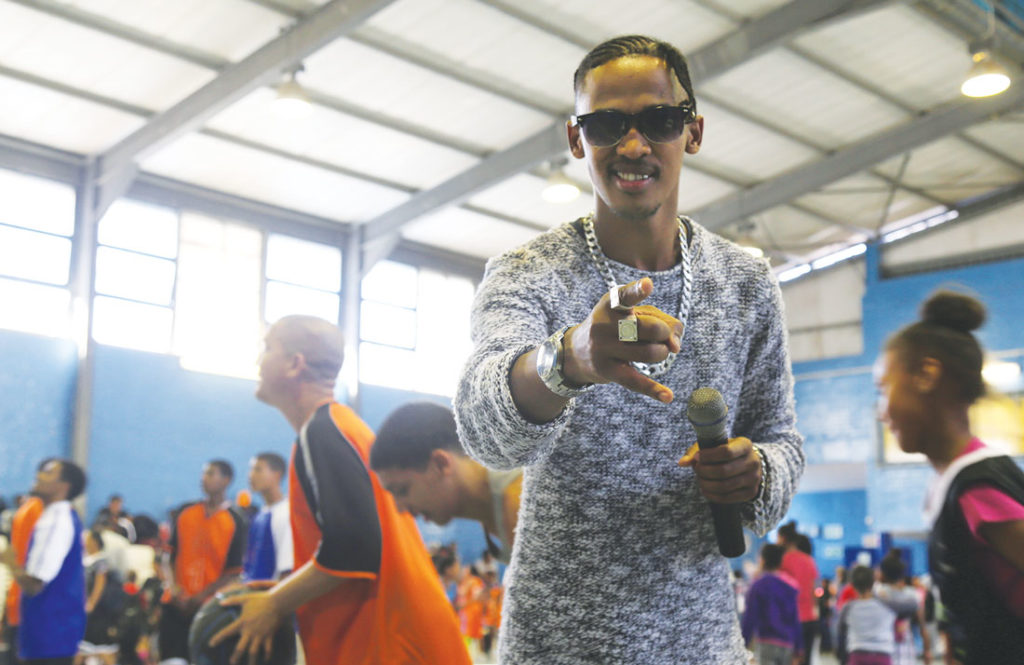

During Youth Day 2017, both Michaels and Lelo helped with events in Hangberg and I.Y. Lelo hosted a soccer game between the black I.Y and colored Hangberg neighborhoods as a way to bring the communities together. Michaels hosted a basketball game at a Hangberg recreational center, with a DJ, dance battle, and food. Michaels, who looked like a local celebrity working the microphone, used the day to honor Hangberg children and tell them to shoot for their goals.

“I’m planting a seed in the community,” he said. “I’m here to encourage the youth, show them you can achieve what you want to achieve in life.”

Lelo’s primary focus on Youth Day was creating oneness. He hoped that through the events and activities of the day, he could bring different communities together. Breaking down the boundaries set by apartheid was his goal.

“The first mission as the chairperson of this branch is to indoctrinate these communities,” Lelo said, “make sure we don’t have a colored side, black side, and the valley,” referring to a high-income area that’s mostly white. “We should live in one community and do things together.”

The mood was lively, and everyone’s hopes were high. I saw face painting and food everywhere. And other community leaders like Lelo and Michaels.

Reality stuck again in I.Y. not long after the celebrations, though. After I had returned home, Michaels told me protests against the government’s handling of the residents displaced during the March fire began less than two weeks after Youth Day 2017. Residents who lost their homes in the blaze were moved to a dirt patch next to a local soccer field. They were living in what looked like a refugee camp. Now that winter had come, which for South Africa starts in June, people were left in the cold without heat. The government said better homes would be built in three months. After four months went by without any progress, heating, or electricity, people took to the streets.

Michaels sent me images of riot police, blocked roads, and fires set in the streets of I.Y., the neighborhood with all the friendly people and children I had just met.

Residents blocked roadways with steel structures and rocks in protest. After fires began, police shot tear gas and rubber bullets at the protestors. Residents demanded a sit-down talk with the city’s mayor.

The images reminded me of what I’ve seen in America over the past few years, such as the Inauguration Day protests and the protests over police brutality in major cities across the country that turned into violence. And the one in Dallas that turned into chaos when a gunman killed several peace officers. It was a revolt of an enraged population against a government they felt didn’t care about them. Tearing down homes and creating fires in the street didn’t seem like it would solve their problems, but what else could they do to make a stand?

Mayor Patricia de Lillie, who is black, didn’t appear to be moved much by the show of resistance. Eventually, she visited the neighborhood to plead for cooperation from the residents but not before she told local news outlets there was no justification for the protestors’ violence and “thuggery.”

Lelo told me this disconnect between the people and their elected officials wasn’t just a problem on the local level. It was common in South African politics in general. He felt the politicians, including the country’s president, Jacob Zuma, pretend to care only when they need votes.

“We have leaders up there who don’t care about the people,” Lelo said. “The only things they care about are themselves. They only want to enrich themselves and their families. That’s it.”

*****

I was naive to the issues South Africans were facing. I had read books and seen movies about the life of the country’s first black president, Nelson Mandela, elected in 1994. The story of a revolution that he led for representation, equality, and change always amazed me. His image was everywhere in the city and surrounding towns. Inspiring quotes from him were printed all over souvenirs. But the circumstances he fought against still impact the people. His election was definitely a step toward change, but an election alone cannot counter centuries of colonialism and decades of apartheid.

Small-town, poor, or uneducated folks weren’t the only ones feeling hardship throughout the country. College graduates complained about not being able to find jobs or to improve their living situations. Lelo said college grads, black ones especially, are unable to find work easily, and when they do, most of their money goes back to their families. Locals refer to the situation that college grads find themselves in as a “black tax.”

“When you go to a university and get employed you are not going to work for yourself,” Lelo said. “You are going to work for your house. We call it a black tax because your family cannot afford food or the clinic. All your money goes to food for you family and then yourself. In the end, you don’t have anything.”

Living the free and easy life of a college-educated, newly employed twentysomething can be difficult when your parents, siblings, and relatives are still housed in a shack without any money for basic necessities. Most of the activists I spoke with said their hopes in improving South Africa’s future lay with the country’s next generation, the kids of today still living the struggle – the same kids who played and danced regardless of their circumstances.

In addition to Michaels’ long list of occupations, he is also an active member of a local child empowerment organization called Harvest Youth Project. Michaels said the children in his community are facing fatherlessness, drug abuse, and “gangsterism,” a term South Africans use to describe a gang or gangster lifestyle. Michaels hoped to be a role model year-round. Being an activist means more than promoting change one day a year on Youth Day.

“I’m just here to inspire the next generation and do what I do best,” Michaels said. “Motivate.”

Lelo felt the same way and believes today’s youth will lead South Africa’s next revolution and instill the unity that others before them fought for.

“I’m positive about this young generation and my generation,” he said. “I believe something big is coming in the next 10 or 15 years, and South Africa will be great. The way forward is for us to come together, united.”

The words from Michaels and Lelo were encouraging. They showed me that even against adversity and possible retribution, they remained hopeful. They would not quit. They would do their best to inspire and make positive changes. They even inspired a young guy from Cowtown in the process.

Diamon,

I also was privileged to meet Peter during my visit to Harvest Youth Project in May! They are doing great work and changing lives. I’m the mom of a TCU ’16 grad, and I would love to see students serving in Hout Bay during summer breaks! Great article!

Proud of you! This is an awesome article! I’m so honored to have shared this experience with you! Best of luck in everything you do!

Good article. I agree. there is a big inequality in our country.

But a lot of the living division is because of people being ahead of others educationally…

and that’s why they can afford nicer places. or perhaps, they inherited money.

I guess, I’m saying to not hate on those who are wealthy. a lot of them worked hard to get there…

a lot of the problem is the false promises of the government who said “nice things” to get votes.

the way forward… is good education for all.

By the way, I earn below middle class… so I don’t comment from a “rich perspective” at all..

my heart breaks, this corruption in our country is so sad.

even the church as a whole seems to be struggling to make an impact…