For a world-class art institution, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art sure has a sporting side. A surprising number of works depict subjects sprinting, punching, exercising, competing, and otherwise engaging in sporting pursuits. What many regard as the institution’s best known work revolves around an aquatic sport. In Thomas Eakins’ “Swimming,” a half-dozen unclad males gather at a country lake. The painting created controversy for the artist while he was serving as a professor at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Swimming, 1885

Photo courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

“You can see [Eakins] with his dog and clearly identify that these are his students,” explained Amon Carter associate curator Maggie Adler. “That was a huge no-no.”

Eakins, she continued, “believed that you should teach art to people using live nude models. That was not allowed if you had men and women in the classroom.”

Eakins would later resign his post after his removal of a loincloth from a classroom model generated more Victorian-era handwringing.

Adler possesses unique qualifications when it comes to examining the representation of sport in art. In addition to her masters in art history from Williams College and experience at multiple museums, the Scarsdale, NY, native excelled as a competitive archer. She shot well enough to try out for the 1996 U.S. Olympic team. She finds a certain similarity between the two pursuits. “I feel the same way entering a competition as I do before I go to give a lecture or talk,” she said, “because you get yourself psyched up. It takes a certain amount of adrenaline.”

Most of the Carter’s sports-related objects tend more toward Adler’s style of sport than stick-and-ball games. Archery figures prominently in a painting that recalls the museum’s own heritage as an institution focused on the American West.

![George Catlin; "Archery of the Apachees [sic]"; ca. 1855; Oil on paper mounted on paperboard; Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, Gift of Paul Mellon; 1986.40](https://www.fwweekly.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Apache-1986-40_pr-300x229.jpg)

Near the Catlin painting on the museum’s second floor, there’s another example of Native Americans engaged in sport. In Seth Eastman’s 1848 work “Ballplay of the Dakota on the St. Peter’s River in Winter,” Sioux athletes play a version of lacrosse. The contest occurs on a frozen river, and the stakes are high. “We think there was gambling involved, so this is maybe why this buffalo hide and arrows … are in the front,” Adler said. “That’s the wager.”

Adler said Eastman’s wife also recorded that this full-contact version of lacrosse often resulted in broken limbs and even deaths.

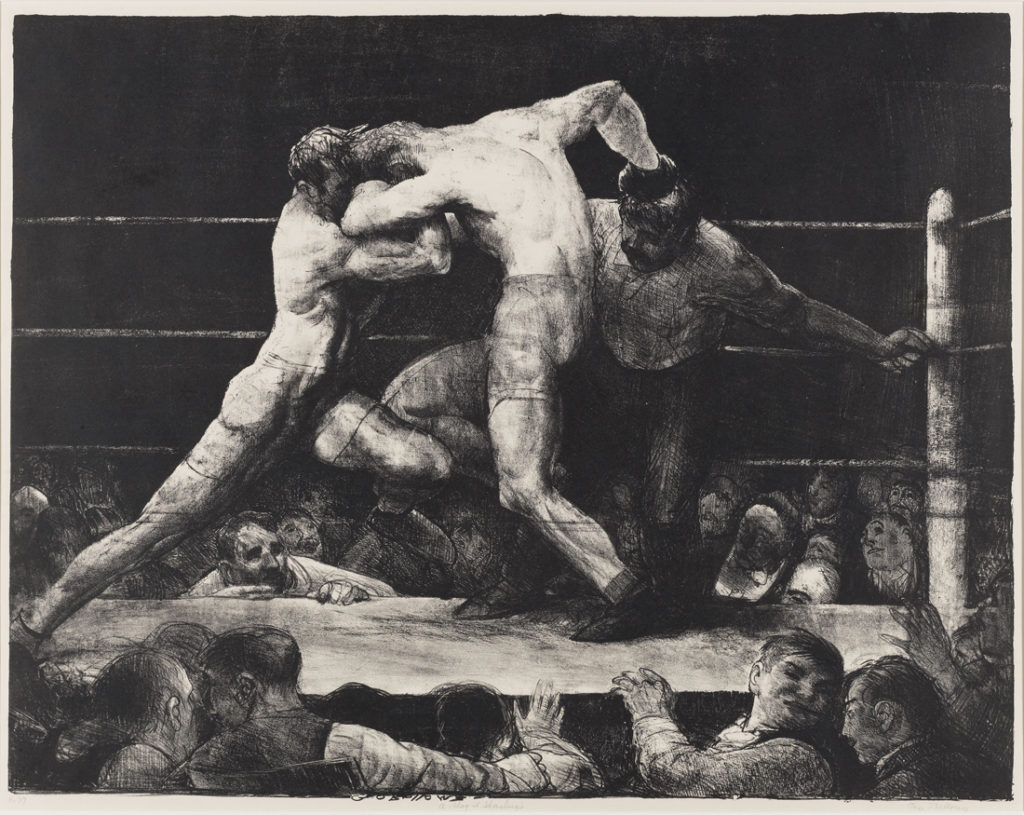

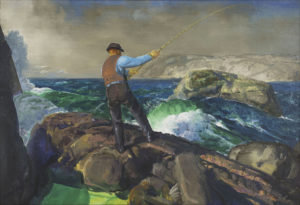

Another athletic pursuit known for its physicality represents perhaps the museum’s most complete archive of any single sport: prints by George Bellows. The museum owns 230 of the former semipro baseball player’s lithographs, including many gritty boxing scenes. A seminal work from 1917, “A Stag at Sharkey’s,” shows two fighters locked in desperate struggle. The museum has the combat scene displayed next to another of Bellows’ creations, the newly acquired 1917 oil painting “The Fisherman.”

Outdoor sports like fishing and hunting represent much of the museum’s sporting archive, though several of the works have gone on a road trip. Adler and collaborators from other museums incorporated a number of the works into a traveling exhibition. Wild Spaces, Open Seasons: Hunting and Fishing in American Art is on view currently at the Shelburne Museum in Vermont and will be in Fort Worth in October.

Each Bellows boxing lithograph can remain on display only for a few months at a time to avoid light-inflicted damage. Like most museums, the Amon Carter owns more pieces than it can display at any one time, so more of its sporting art may make its way into the walls in the future.

For more on the Amon Carter and the roots of the sport of rodeo, check out this week’s Sports Rush post in the Blotch section at fwweekly.com.