Byron Livingston was healing from a broken marriage when he took a Spanish class at Tarrant County College in Arlington a decade ago. An environmental and health safety regional manager for Fastenal, a commercial and industrial equipment supplier, the father of three took the course to better communicate with Hispanic clients. The class was a diversion from the divorce that he and his wife had amicably agreed upon after having grown apart.

It was through the Spanish instructor that Byron found out about a musical performance that was to be held on campus. The instructor had invited students from his classes.

“I thought it would be interesting to do during lunch,” said Byron, 55.

At the show, Byron, himself an older student, sat next to another “non-trad” – an attractive woman close to his own age who was in the instructor’s other class. They struck up a conversation.

“She seemed to have it all together,” Byron said of the 5-foot-2 blue-eyed blonde and mother of two daughters.

Three years later, the two married. It wasn’t long, though, before trouble seeped into the marriage. Byron came home one day to find his wife sitting at the computer, angry. At him.

“She had a separate bank account and she thought I was breaking into it,” Byron said. “She thought I was resetting her passwords and taking things from her that she couldn’t find. She even accused me of putting video cameras in our smoke detectors.”

Byron also said Charlott accused him of putting a GPS on her car as another way of spying on her.

At first, Byron was able to cope with his new bride’s strange bouts of paranoia. But then they got worse and more frequent. Two or three years into the marriage, he knew he was in trouble.

“There were very volatile situations – lots of yelling, calling me names, cursing,” he said. “She was calling me every name in the book and saying I couldn’t be trusted. Then the next minute she would be fine. She could switch it on and off.”

Alcohol, as well as drugs – prescription and otherwise – made things worse. Byron said Charlott began drinking a bottle of wine every night, sometimes more.

“I would bring up, ‘Hey, you’re kind of drinking a lot,’ ” he said. “She would be either real amorous, or real pissed off, but mostly pissed off. I remember thinking, ‘Which Charlott am I going to get?’ I tried to bring up that I was concerned about her several different times, several different ways, and then just finally gave up.”

Byron said that Charlott took medication for migraines and, after undergoing chemotherapy for Lymphoma, was on prescription meds that contained hydrocodone, a pain reliever that can be habit-forming and can cause abnormal feelings of sadness. She had a history of using methamphetamines, Byron also said, and he heard that she’d used cocaine at one time in her life.

The breaking point for Byron came on New Year’s Day last year, when Charlott became enraged at his daughter, Lauren, now 23, over an issue related to her wedding. Byron felt that Charlott overreacted and was needlessly offended. Charlott had never liked Lauren, he said, even though his daughter was just 12 when the two met.

Lauren’s wedding was “already a huge stress for me with my family because of Charlott’s actions,” Byron said. “I had spent way too much time stressed out, crying, wondering what I was going to do about my situation. That was just the [last] straw.”

The next day – January 2, 2016 – Byron moved out of his and Charlott’s Mansfield home.

“She was all for it,” he said. “She’d been telling me that I was a liar and no good, that I was the reason she was depressed.”

Despite Charlott’s agreement to the split, the divorce was rocky because, well, everything was rocky where Charlott was concerned. There were times when she called the Mansfield police to accuse her estranged husband of breaking into the house and taking her things. Once, she even asked officers to dust a handprint on a mirror, convinced the fingerprints would prove that her husband was having an affair with her best friend and that they’d had sex in the house. The accusation was false, Byron said, and it ended the friendship.

That friend, Joni Ortiz of Kilgore, said that she and Charlott had become friends years earlier, when she was an interior designer for property that Charlott had invested in. She said that Charlott’s bizarre accusation came as a total shock.

“I gave her an opportunity to apologize to me, and I told her the ball was in her court,” Ortiz said.

The apology never came.

Byron said Charlott “made it as difficult as she possibly could to get divorced from her, even though she told everybody that she wanted to divorce me.”

The divorce was final last October, but that didn’t end the drama. The following month – on the day before Thanksgiving – Byron and his new girlfriend Paula phoned 911 when Charlott showed up at the Mansfield house on Laura Elizabeth Trail. Byron had owned the house prior to the marriage and was given possession of it in the divorce. Charlott had moved out, and he had moved in. He and Paula were watching a movie, he said, when Charlott began banging on the front door, demanding that she be allowed to retrieve Christmas decorations from the attic.

“She said, ‘I’m not going to bother you and whatever whore you have in there,’ ” Byron recalled. “Poor Paula. She’d known me two weeks.”

At first, Byron refused to open the door, but then he relented, thinking that maybe if he let Charlott retrieve the decorations, she would leave him and Paula in peace. Instead, Charlott became angrier. She threw things down from the attic, Byron said, aiming at a gift he had in the garage for his son. She also caused a scene in the front yard. He and Paula called police. When Charlott saw a squad car approaching, she took off, only to return again a short time later, Byron said, “making wild accusations.”

Paula called the police again. When they arrived, Charlott turned her anger toward them, Byron said, yelling and cursing at them. To his surprise, they did not arrest her.

“If I’d been doing the same thing, I’d have been in jail,” Byron said. “The Mansfield police never did anything about Charlott.”

He said they also had taken no action when Charlott was living in the house and changed the locks despite a court order allowing him to enter the home to retrieve his possessions.

“They said, ‘Well, we’re not here to be the middle man,’ ” he said.

Just before 10 a.m. on Thanksgiving, the day after the scene in the front yard, Byron called police yet again. Sometime during the night, someone – presumably Charlott – had keyed or otherwise scratched Paula’s red 2015 Civic and Byron’s black 2011 Elantra. Ultimately, the pair opted not to press charges since there was no proof Charlott had done the damage and little chance she would confess to the crime.

Byron moved forward with his new life post-Charlott. He sold the Mansfield house and moved in with some buddies in Flower Mound, where Paula lives. During that time of transition, he used his parents’ home in Cedar Hill as his mailing address.

Byron spent the evening of Monday, Feb. 13, at Paula’s house watching The Sopranos with her. When he left sometime between 9:30 and 10 p.m., he realized that he had missed a phone call from his father. When Byron returned the call, his father told him that Cedar Hill police were there, having been given that address by Mansfield police. An officer took the phone and told Byron that the Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s office needed to speak with him.

“Right then, I knew it was Charlott,” Byron said. “Charlott was on such a downhill spiral, and we all knew it.”

Byron phoned the ME’s office and was not surprised when his assumption that Charlott had committed suicide was confirmed. Nevertheless, something the man said did deliver a shock. He referred to “bodies.” Plural.

Prelude to a Murder

Prelude to a Murder

Nine weeks had passed since the horrific murder-suicide at the Hilton in downtown Fort Worth when Candice Norman, Charlott’s oldest daughter, walked through the door of a coffee house in Watauga, where she lives with her fiancé Bill Guzman, who drives a big-rig truck, and their three young daughters. She took a seat at the table I had commandeered minutes earlier and, though smiling, started off our three-hour conversation by stating that it had thus far been a rough day.

“It just comes and goes,” the 31-year-old said of the waves of shock and grief that are still fresh.

Candice lost her father, Timothy Norman, to cancer when she was 8 and he was 38. The family was living in Florida, where Timothy owned a gutter company. He’d had a mole removed from his back, but the tissue wasn’t tested. Three years later, after he developed headaches, doctors discovered that he had cancer and that it had invaded his brain. It was determined that the cancer dated back to the mole.

After his death, Candice said, the widowed Charlott received $2 million in a malpractice claim. Half went to Charlott. The other half was put into a trust for Candice and her younger sister, Melissa. Pretty quickly after obtaining the money, Charlott uprooted the two girls and moved to Texas, where she had been raised and where she now had a boyfriend.

That was the start of Candice’s resentment toward her mother.

“She just didn’t care about me and Melissa,” Candice said of Charlott. “It was guys and partying, guys and partying. She got us a live-in nanny.”

There were lots of vacations to places such as Hawaii and Aruba, but they weren’t family vacations. Charlott went without her daughters. Candice said the only vacation she and Melissa were treated to was a trip to San Antonio. Charlott blew through her million, Candice said, and then began fudging receipts to justify taking money from her daughters’ trust.

At age 12, Candice began using meth, provided by the stepfather of a friend. Charlott was using, too, she said. At 15, Candice gave birth to a girl. Candice said she was “so wasted” at the time Fayth was conceived that she wasn’t sure of the father’s identity. When Candice was 16, she was sent by her mother to rehab in Utah. While still a teen, Candice gave birth again, to another girl. The child is now 12 and lives with her father in Colorado. During Candice’s years of teen pregnancies and drug use, CPS became involved. When Fayth was 5, Charlott was awarded legal custody of her.

Over the years, Candice’s and Charlott’s relationship continued to be turbulent. Charlott, Candice said, thought she could see spirits and demons. She set up a camera in Candice’s bedroom when she was pregnant with Fayth, convinced she would see demons on her daughter.

Eventually, Candice weaned herself off drugs. She celebrated nine years of sobriety last February. Charlott, though, was not doing as well. In addition to the end of her marriage, she was unemployed, despite her intelligence and master’s degree in business communications. According to Candice, Charlott had previously taught a communications class at a community college and taught at Cedar Hill High School, but the public school job lasted for just one academic year. Charlott told family members the class was eliminated.

During the divorce, Candice testified in court, not on behalf of her mother but for Byron.

“It got to a point where she was so hateful and so mean to him all the time,” Candice said of her mother. “Everything was his fault. He was a horrible person. She was just very, very hateful. She wanted him out of the house. He finally agreed to go stay with a friend, and when he got out of the house, it was like, wow, this is awesome. And he came back and said, ‘You know what? I think divorce is in our future.’ And that’s when she flipped out. Then she tried to say, ‘You left us, and you said you’d never leave us’ – even though it was her pushing him out the door.”

While Byron was in the picture, Candice felt that Fayth was OK, regardless of Charlott’s paranoia and rages. But once he moved out, she began to worry. Candice’s concern increased when Charlott blocked the young teenager from communicating with family members via text and Facebook. Fayth, though, secretly kept in contact with her family through Snapchat, a mobile app that allows users to capture videos and photos that self-destruct within seconds. Byron and Melissa confirmed this.

According to Candice, Fayth phoned CPS in October when Charlott left her in the care of a neighbor and checked herself into a drug rehab facility in California. Candice said that Fayth was upset because she wanted to stay with family and was tired of Charlott’s neglect. Candice said that she and other family members contacted CPS as well but never heard back from the agency.

After the stint in rehab, Charlott moved with Fayth into the home of Charlott’s mother in Covington, 12 miles north of Hillsboro. On December 27, 2016, Candice, Bill, and their three daughters, as well as Melissa and her two children, drove to Covington to celebrate Fayth’s 15th birthday. Charlott was on her best behavior. She had even baked a German chocolate cake that everyone enjoyed after a lunch of sloppy joes and chips.

But, in typical Charlott fashion, the good vibes soured a few days later. She phoned Candice and asked if she knew what had happened to her handgun, which had been at the house at the time of the birthday gathering. The question, in Candice’s mind, was a passive aggressive accusation.

On Saturday, Feb. 11, Candice saw a photo that Fayth posted on Snapchat, her lifeline to family members. Fayth had taken the photo from a seventh floor room at the Hilton, where she and Charlott had checked in for the weekend. Candice was happy that her daughter was enjoying a weekend getaway.

She didn’t think much more about it until just before midnight that following Monday, when she was awakened by knocks on her front door. When she looked through the peephole and saw family members, she knew.

Descent

In Candice’s view, it’s hard to say when her mother crossed the line into what, presumably, was mental illness. Charlott had always been difficult, and her behavior was made worse by drugs and alcohol. Her mental state seemed to be a chicken-or-the-egg type of situation.

Candice’s older sister, Melissa, who’s now 24, remembers a childhood of nannies, babysitters, and “being at friends’ houses a lot.” Charlott, she said, “wasn’t as nurturing as she thought she was.”

Within a second, Melissa said, “she could [become] very hateful and controlling.”

Charlott’s emotional unavailability to her daughters continued through the last year of her life, when Melissa’s long-term relationship with the father of her children came to an end.

Melissa said, “She basically told me at the beginning of the year, ‘I know you’re going to need me, but I’m simply not going to be there for you. I have my own issues, and I don’t have time to deal with yours.’ ”

Candice and Melissa believe Charlott may have suffered from multiple personalities and likely was bipolar. Melissa said Charlott once told her that she had “an issue with meth.” Melissa believes her mother had an addictive personality and that meth was a gateway, making her vulnerable to painkillers when she later fought Lymphoma.

“She did struggle her whole life, but it was nothing compared to this past year,” Melissa said. “She completely hit rock bottom, and she just couldn’t get up this time.”

Candice showed me a lengthy text message sent to her by one of Charlott’s alleged former boyfriends. It confirms Byron’s story about Charlott changing the locks at the Mansfield house.

“The last time I saw her was in July 2016,” the man texted, after Charlott’s death in February. “She called me out of nowhere needing her locks changed. (I used to be a locksmith and alarm tech.) She told me she was getting a divorce. After meeting with her I knew something wasn’t right with her. And from the past experiences, I didn’t want to get involved so I hired a locksmith friend to re-key the house. I gave her some money … and then I stopped taking her calls and texts.” (His ellipsis.)

The man related that he met with Charlott at the Mansfield house after she reached out to him for help but that she was not the same “articulate and outgoing” woman he had known for years. Instead, according to his text to Candice, Charlott was “unemotional, slow in her actions and talking with slurred speech.”

He texted, “I asked if she was on drugs and she said she had a prescription for OxyContin. Then she was showing signs of being paranoid, like wanting me to check her house, attic, computer, phone and car for bugs and cameras. She would lose her train of thought while talking. I loved Charlott since she was 13 but I know if you ever crossed her or pissed her off, you will pay.”

The man texted that he followed through with getting the locks changed, then “disappeared.”

Another person in Charlott’s life, Buck Jenkins, said she was “very manipulative” and could be “a bitch.”

Jenkins entered Charlott’s and Fayth’s life three years ago, after a DNA test proved him to be Fayth’s father. Contrary to Candice’s claim that CPS never followed up on allegations against Charlott, he said the agency did follow up – at least where he and his wife were concerned.

“They spoke with me on two different occasions,” he said. “And they spoke with my wife.”

As for Charlott’s alleged mental illness, he defended CPS, saying, “There was just no proof.”

Buck said that Fayth and Charlott argued at times and that Charlott would phone him during the disagreements, even as late as midnight. Candice and Melissa said that Fayth was torn because, even though life with her grandmother was difficult, she nevertheless loved her and didn’t want her to be alone.

“As bad as things would get, Fayth wanted to protect her Nanna, and she didn’t want us to worry,” Melissa said.

Fayth not only endured her own struggles with Charlott, she also witnessed ugly scenes between her grandmother and others. Byron said that, on the day before Thanksgiving, when he and Paula called the police on Charlott, Fayth was with her. While Charlott was screaming obscenities at police officers, Fayth, then 14, walked up to the front porch where he was standing with Paula and asked him if he could help her “with her situation.” But since he was no longer her stepfather Byron had no legal standing where Fayth was concerned. He felt that the only advice he could give was for her to stay in contact with his daughters.

Buck said he told Fayth in late December that she could come live with him and his family at their home in Grandview, in Johnson County. Charlott, he said, “was fixing to let me have her.”

Candice’s claims about CPS having been contacted about Charlott last October are true. Normally, CPS reports aren’t available through the Freedom of Information Act, but documentation was released by the agency through FOIA after the Fort Worth Police Department closed its investigation. The paperwork shows that CPS opened an investigation of Charlott on October 10 of last year, though it does not reveal the name or names of those who contacted the agency.

The report states, “It was reported that the deceased child’s maternal grandmother was abusing prescription medications that would often render her unconscious and unable to provide adequate supervision and needs for the deceased child. Further it was mentioned that the deceased child’s grandmother had ‘suicidal tendencies’ and a history of using methamphetamine.”

If, as Candice claims, Fayth herself phoned CPS asking for help, loyalty to her grandmother may have sealed her doom. According to the report, the case was closed after both Fayth and Charlott denied the allegations.

Buck noted that, on the day Charlott headed with Fayth to Fort Worth, “she had to drive right by Grandview.”

She could have dropped Fayth off at his house, he said.

But she didn’t.

“It’s Time”

“It’s Time”

Sitting inside the Watauga coffeehouse, Candice described the chain of events, as told to her by police investigators. I was unable to obtain reports and witness statements through open records requests because of a law mandating that documents in child abuse cases not be released.

(I did succeed, though, in later helping Candice, as the mother of the murder victim, gain access to parts of the investigation file through her own open records request. The city is seeking an attorney general opinion on some items in the file.)

Around 4 p.m. on Monday, the day before Valentine’s Day and two days after Charlott and Fayth checked into the downtown Hilton, a maid entered their room. It was pitch black, like a tomb, the thick curtains closed as if to block out the world. Two people appeared to be lying in the bed. The maid assumed they were sleeping, even though it was an odd time of day to be doing so, and well past checkout time.

The maid reported to the manager that the guests in that room needed to be rousted and told to check out. The manager summoned the hotel’s head of security, and the two headed to the seventh floor. They quickly realized that the bed’s occupants weren’t sleeping. They were dead.

Police investigators believe, based on the last time the room key was used, that Charlott shot Fayth sometime after midnight as she slept, Candice said. No guests reported hearing gunfire. The two had gone out to dinner that night and had stopped for drinks at a nearby Jamba Juice. The receipt was found in the hotel room, Candice said, and showed the purchase to have been made shortly before 9 p.m.

Even though they were a good distance from home, Fayth happened to encounter a school friend at Jamba Juice. Fayth told the friend that she and her grandmother were going to see A Dog’s Purpose the next day, a movie about a devoted pet who is reincarnated several times and teaches humans how to laugh and love.

Candice said that her mother packed a bizarre assortment of items to take to the Hilton: court papers from 1998 concerning Charlott’s mother as well as her mother’s car title; Charlott’s father’s death certificate, also from 1998; Charlott’s and Byron’s marriage license and divorce decree; and “every single driver’s license she had in her whole life,” Candice said. Charlott also brought her handgun license and “tons of pills,” from vitamins to Codine, Candice said.

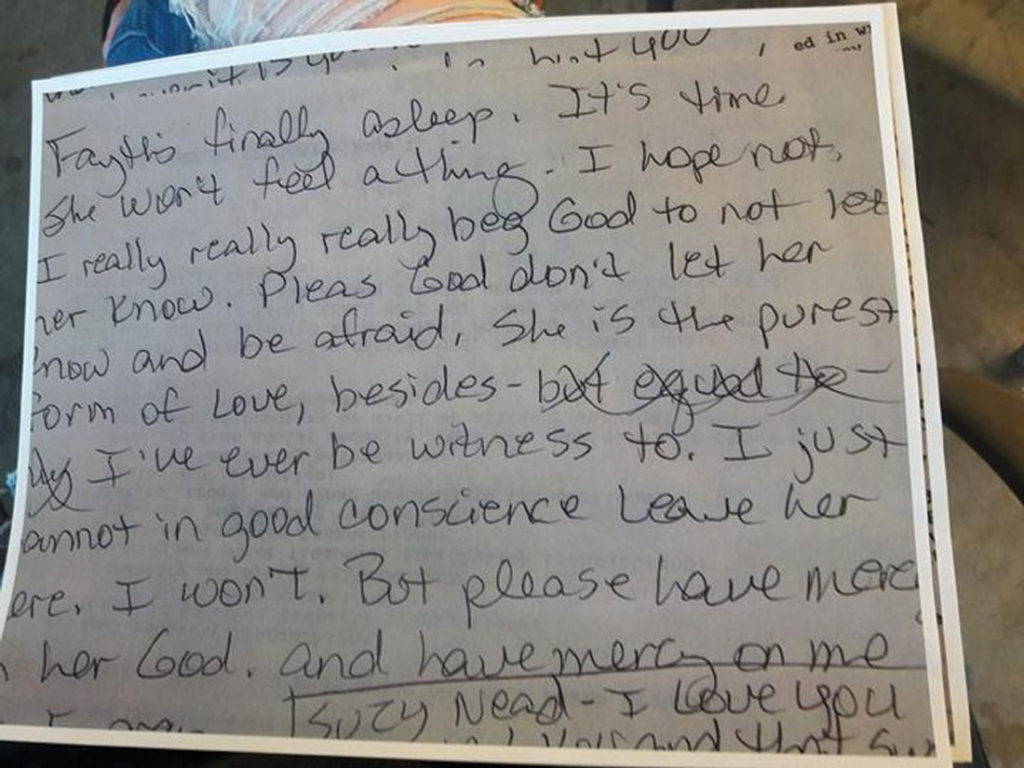

Although Charlott brought notebooks full of blank paper, Candice said, she scrawled her lengthy, rambling suicide note on the back of an old power-of-attorney document. Most jolting to Candice and other family members was that the letter contained very different types of handwriting and expressed opposing emotions.

In some passages, Charlott’s handwriting is clear, and she expresses positive thoughts toward others. But there are also angry-looking, hard-to-read scrawls in which Charlott spewed vile insults to Byron, her own mother, and others in her life.

“Her handwriting could be perfectly fine, and then it was like a 4-year-old writing left-handed,” Candice said.

In the note, Charlott spoke lovingly of Fayth yet, in another passage, referred to her “lack of maturity” and “unwillingness to follow directions.”

“She thinks she wants to live,” Charlott wrote. “Have a life with a husband, family, wonderful career … [Ellipsis added.] So naïve. She simply doesn’t understand that there’s no hope of that.”

In her final communication to almost everyone in her life, Charlott complained about having been late to dinner because of faulty GPS directions. She wrote that she looked “like shit. No shower, no make-up, no tan, no hair done –– just looking like shit and seeing all the pretty people tonight.” She even bemoaned that she had not been able to afford a pedicure in two years.

As her granddaughter lay with a heavy dose of Benadryl in her system, Charlott wrote, “Fayth is finally asleep. It’s time. She’s won’t feel a thing … [Ellipsis added.] Please God don’t let her know and be afraid. She is the purest form of love.”

Before putting the barrel of her 9mm handgun in her own mouth and pulling the trigger, Charlott put the firearm against the back of her granddaughter’s head and sent a bullet ripping through her dreams.

Postmortem

Byron said he feels sorry for Charlott and never hated her. Melissa said she may one day be able to forgive her mother, but right now, no. She’s still not over the shock – or the confusion. She said that at 3 p.m. that Saturday, just hours before committing her unspeakable act, Charlott was actually behaving like a mother. She texted advice to her about how to choose an electric provider.

“She was completely normal,” Melissa said.

Candice refuses to forgive her mother because she believes Charlott knew that she had a mental illness yet refused to get help. In her view, this strange excerpt of Charlott’s suicide note confirms this: “Candice – if you don’t do anything else I’ve ever taught you, told you, talked to you about, please get help for your mental illness/Bi-Polar/depression, whatever you want to call it.”

She added a warning: “It will destroy you and everything you care about. The struggle is real.”

Fayth was cremated. Most of her ashes are, for now at least, in her mother’s closet. Candice ordered an urn necklace with a heart and a flower of teal, Fayth’s favorite color. On the Saturday afternoon that Candice and I talked at the coffee house, the necklace had not yet arrived because it was being engraved with the words “Fly high, Faythy” and, on the back, “I love you bigger than the sky.”

Some of Fayth’s ashes were taken by a cousin to be spread in New York. A family friend took some to the Bahamas. Candice said she is going to make a photo album of the places where her daughter’s ashes have been spread, places she will never get to go with the husband and children she had dreamed of.

As for Charlott, her body, too, was incinerated – fitting, perhaps, for a woman who had burned every bridge. At the time of this writing, her ashes remain unclaimed at a funeral home in south Fort Worth.

“She always claimed that she had this horrible, hard life, and she wished she had a good life and a good family,” Byron said. “Well, she had all of that at her fingertips. The thing she was looking for was in her grasp, but she didn’t know how to treat it and she ended up losing it.”

The child who loved Charlott despite everything was the person to whom Charlott would, in her final act, inflict the greatest cruelty.

“But please have mercy on her God,” Charlott wrote in her suicide note.

Then, in clear, cogent handwriting, she added, “And have mercy on me too.”

Your article is sided and unfair. I do not condone what Charlotte did but in all fairness, Charlott was not herself, she was depressed and on medication. About a month prior to the murder suicide, a family member found Charlott in the shower with a loaded gun in her mouth. Where was CPS? Why was she still allowed to have custody of Fayth after this incident happened? From what I have just read from you totally one sided article is a woman repeatedly crying out for help. If you could see her Facebook pictures and posts you would see a loving Mother and Grandmother. Pictures of birthday parties, baby showers, graduations, etc… and a supposedly loving husband who after shaving off Charlott’s hair, shaved off his in support. Charlott was diagnosed with beast cancer in the spring of 2013. she was not expected to live.

The last time that I spoke to Charlotte was back in October of 2016. Charlott wanted to come and visit me in Montana but the airline tickets were too much and we decided on a late date. My regret and sadness is that I did not hear the desperation and cry for help in her voice. I was too busy with my own life to hear the need for help in he voice. Maybe if I had taken the time this horrible event would not have happened.

Charlott is not the monster that you are portraying her as in this article. Charlott needed help and we were not there to help.

We all saw the signs but chose to ignore them. How can you blame a mentally disabled person.

Ms. Solano:

The story was not meant to portray Charlott as “a monster” but rather to depict the reality behind tragedies such as this one. In this case, that reality may be viewed by some as controversial since Charlott’s daughters held deep resentments toward her well before the presumed mental illness took hold. Part of the truth behind mental illness is that often, for those closest to the sufferer, it all simply becomes too much. You asked, “Where was CPS?” That is a good question. Though some family members criticized CPS, Fayth’s biological father defended the agency, saying that there was simply “no proof” of Charlott’s alleged mental illness. He and others said that she had the ability to “turn it on and off” and that she could appear quite normal. This will hopefully serve as a lesson to CPS that mental illness can be deceptive, and that children may sometimes lie because they are afraid or because they are conflicted by feelings of loyalty to their caregivers. This tragedy will also hopefully inspire others to speak out – and speak loudly – when they have reason to believe that a parent or caregiver may have a mental illness. You wrote: “We all saw the signs but chose to ignore them.” I am casting no blame here, but your comment cements the importance of taking action when there are indicators that someone may be a danger to themselves or others.

This woman had a least a decade of “problems” . She was a manipulator, liar and thief. She was incredibly selfish and used drugs and alcohol. She was a monster for murdering her grandchild. I do not see anything worthwhile in trying to get a sociopath “help”. If it isn’t prescription drugs it’s other illicit drugs. Did she ever have a job outside of tormenting and ripping off those around her? She even thought that God was at her beck and call-go figure.