In his own words, Josh Fleming is a writer, but you could also say he’s a talker, certainly so when it comes to his own music. Telling a journalist that he’s a writer while talking about his own band might come off as incorrigibly self-promotional, but if you split the difference between the two designators, the identity in the middle is “storyteller.” And Fleming has lots of stories, more so when there are some beers involved. And he and I had some beers. More than some, in fact. As he and I got looser, I realized that telling stories is pretty much what Fleming was born to do. And seeing as how his band, the punked-up country act The Vandoliers, is putting out its sophomore album, The Native, on a kind-of-a-big-deal record label, it looks like Fleming and his crew of rowdy, Stetson-sporting chord-slingers are going to be telling his stories to a wider audience far into the foreseeable future.

The Vandoliers, technically, are Dallas-based, but that’s probably because some of them live there now. And for a time, so did Fleming. But now he’s back in Tarrant County, living with his wife in North Richland Hills. And he couldn’t be happier.

“We can go have a date night in the Mid-Cities and actually get to hang out [together] rather than constantly stopping to talk to other band dudes at the bar,” he said.

The freckle-faced, denim-clad 28-year-old singer-songwriter/guitarist met me for a weekday happy hour at A Great Notion, the legendary Ridgmar neighborhood watering hole that I visit from time to time, partly because I can walk there from my apartment but also because it’s frequented by talkers. Drop by on any given afternoon, and you’ll hear the regulars spin outrageous tales of Westside hijinks that go back decades. And like I said, Fleming is a talker. He fit right in.

The first things he told me had to do with the record deal he signed with Soundly Music, a subsidiary of Thirty Tigers, the Nashville-based entertainment company founded by Grammy-winning producer David Macias (LeAnn Rimes, Son Volt, Patty Griffin), as well as Dallas-based State Fair Records and Infinity Cat, a cassette imprint also out of Nashville known for pressing runs of marquee rock bands like JEFF the Brotherhood. The way Fleming tells it, Macias took interest in The Vandoliers just prior to this year’s South by Southwest. He didn’t really get into the nuts and bolts of the deal, but the band had played a show, and he met Macias at a bar and was pretty upfront about working with the producer’s company.

They were having beers at YETI, the sporting goods company’s flagship store-turned-pop-up-venue where Thirty Tigers artists played a BMI showcase. Fleming declined to say how it happened, but apparently Macias told him he loved the record and wanted to see what it could do. And the way for that to happen, Macias reportedly told Fleming, was to put it out on Soundly.

“And they’ve taken everything to another level for us,” Fleming said.

Fleming mentioned Soundly’s radio promoter and then warned me that he was going start dropping names – they fell like a breadcrumb trail to music festival stardom: Chris Stapleton, Nikki Lane, Jonathan Tyler, even the legendary Dwight Yoakam. Clearly, affiliation with Soundly has opened a lot of doors.

“We got to play Old 97s’ County Fair Festival in Dallas, and I got to meet a lot of people I’ve always looked up to,” Fleming said. “It was really rad feeling like an equal in that environment for the first time.”

Fleming went on to say that his previous band, the hard-rocking Phuss, indeed toured with The Toadies, but Fleming said he never felt on their level, even though Toadies frontman Vaden Todd Lewis had produced The Phuss’ album at the time.

I thought it was probably a good point to discuss the rock band that Fleming co-founded in 2008 with drummer Trey Alfaro, which disintegrated seven years later in a drunken show at The Grotto. Along with Alfaro and bassist Forrest Barton, Fleming pushed The Phuss further than most local bands end up going. But even with three records and thousands of miles logged while touring the country, The Phuss never really met Fleming’s songwriting aspirations, he said. Sure, The Vandoliers are making his dreams a reality, but he really gave it a go with The Phuss. But one of the problems with that band is that it was ultimately another failed attempt at figuring out what he wanted to do with his musical ambitions. In fact, it was more like the fourth or fifth attempt, the latest in a series of trial-and-error bands that began when he was a junior high student in Keller.

To understand how Fleming got from fumbling his way through a middle-school battle of the bands to founding a punk-influenced country group with a record deal and a tour that’s currently crisscrossing the country from now until October, you have to go back to when he was a kid going on fishing trips to Port Aransas with his father.

“I would go on these road trips with my dad, and he was really into country music,” Fleming said. “He introduced me to Joe Ely and Asleep at the Wheel, and he loved Robert Earl Keen. And it’s what? A nine-hour drive to Port Aransas? So we’d listen to all this country music, but once in a while, I’d get to throw in a punk album, which was usually Social Distortion or Flogging Molly.”

He told me how he had gotten into pop punk through Bad Religion and Bowling for Soup – and, in fact, BFS frontman Jaret Reddick lends vocals to a couple of songs on The Native – and later saw Blink-182.

“They sucked,” Fleming recalled, “but I thought, ‘Hey. If they could do it, so could I.’ ”

Later he formed a short-lived garage band with a middle-school friend, Ryan Spears (now frontman of Fairmount-area stoner-rockers Vicious Firs). After that, he started a ska band called The Goners.

“Here’s what’s funny about my ska band,” Fleming said. “I called it The Goners because that’s what me and Ryan called that first band. But we broke up before a show. Unfortunately, I’d printed up a hundred shirts that said ‘The Goners’ on them. I was stuck with these shirts, but there was a battle of the bands at my church coming up. I was really into The Specials, so I basically turned The Goners into a ska band with some dudes I met.”

Fleming worked on his songcraft in high school playing with The Goners, and they ended up opening for a lot of national ska bands touring through North Texas. But unsurprisingly, playing ska wasn’t the right fit for Fleming either. And then he got into drugs, which distracted him further.

“I basically got addicted to ecstasy and turned into a garbage human being for about a year,” he said.

But despite his problems, Disney became interested in what he and The Goners had been doing, though the entertainment monolith wanted a different sound.

“Disney talked to me about doing a non-ska project,” Fleming recalled. “That made the band mad, so they kicked me out, and I started this other band, and it was a fucking failure. It was called Jennifer, which was from a mockumentary called Hardcore Logo. There’s this guy named Billy Talent who’s in this band called Jennifer, and the old lead singer of Hardcore Logo is mad at him because he’s doing good, so I named the band Jennifer.”

Jennifer made what Fleming describes as a quasi-religious space rock album “that Disney thought was a piece of shit.” The label dropped him.

He also got deeper into drugs, but he kept trying to hit it big with music.

“I had a disco band called Midnight Broadcast that was awful, basically watching a downward spiral onstage. But the drummer for that band was Trey [Alfaro], who would later start The Phuss with me.”

Midnight Broadcast went offline in 2007, but Fleming had written a bunch of rock songs with Alfaro. They ended up becoming The Phuss’ debut album, Wanted. They were recorded at the audio engineering school Fleming was attending with producer Tim Kimzie (Vanilla Ice, Pantera). Barton jumped on board not long afterward.

“While I was trying to write true music [in The Phuss] about me, about who I am and where I was, I felt like there were a lot of distractions,” Fleming said.

Trying to keep up with other hot local bands was a big one, especially The Longshots and Mothership.

“I was watching all these cats getting picked up next to us, and it wasn’t happening for us,” Fleming said. “We really tried to be a regional band, but we were an aggressive band, and it ended up being hard to book.”

What he means by “aggressive” is that though he thought he was writing pop songs (albeit songs about drinking, smoking, and getting laid), the band’s sound got louder and more hard-rock oriented.

“I had a loud drummer and a loud bassist, and they in turn made me play louder,” he said. “And we were stuck in this period between the descent of garage rock and the ascent of stoner metal. … We were this middle-of-the-road band, between both, and that wasn’t a good place to be, because you didn’t fit with either side when it came to booking.”

The Phuss eventually ground to a halt. Fleming said that at their last show, he was so wasted that he fell over three songs in and Alfaro literally threw his drums at him. But before that final act, Fleming had done a lot of thinking about where he wanted to be as a songwriter.

“I’ve realized since then that my biggest failure as a writer, from the day I started playing music to the day I started Vandoliers, is that I’ve always tried to keep up with other people,” he said. “It’s kinda superficial. I see my friends succeeding, and I’m 28 now, not really young but not old, and that’s what The Native is kind of about, but it wasn’t until Vandoliers that I just wrote for sake of writing.”

What led to that epiphany is a little horrifying. The Phuss had gotten off a month-long tour and Fleming caught a bad case of the flu: “There was a stomach virus going around in 2014, and that shit got in my eyes.”

Fleming literally went blind for about eight weeks.

“At the end of it, like November of 2014, I started to be able to see again, but I didn’t want to go to work because I was a barber and didn’t want to touch anyone, obviously. I was out of work for the month that The Phuss had been on tour, then another eight or nine weeks of being out of work from being sick. So I’m just sitting around watching TV.”

As mopey as that may sound, his period of idle recovery in front of the TV was exactly what he needed to get to where he is now. And it started with the The Marty Stuart Show.

The former guitarist for Johnny Cash, Stuart had a show that was a “cheesy country showcase kind of thing,” Fleming said.

“And Marty introduces this 90-year-old mandolin player, who comes out and shreds like a metalhead. … And I’m sick, and I realize that I’m getting older, and I’m gonna probably keep getting sick, and that sucks. And I’m thinking how am I gonna be a musician because I blamed being sick on the last Phuss tour, but I see this old man playing country, and all these country guys were the best musicians I’d seen in my entire life. And I remember running into the bedroom where my wife was sleeping, and I woke her up to rave about Marty Stuart. I was like, ‘He’s like if Marc Bolan played country!’ because he’s wearing this glittery suit and has a mullet and a scarf, and I’m really into T-Rex. And my wife was annoyed because I didn’t already know who Marty Stuart was, and she went back to sleep. But I basically spewed out like 30 songs that weekend, all of Amerikinda [the Vandoliers’ first album] and a couple that went on The Native. … I hadn’t been able to write because I was sick, and the first song I wrote was ‘Don’t Tell Me What to Do’ from Amerikinda, because I was telling myself it doesn’t matter what genre you write in. Just write a good song.”

In Fleming’s view, the stuff he’d been writing for his ska band and his rock band fit just as well in a different idiom.

“I learned that a great punk song can be a great country song,” he said. “I’d already fallen in love with country from when I was a kid, and I showed my dad the [new country] songs, and he dug them. And when I showed him the songs from The Native, he didn’t get mad at me for quitting my job.”

Oh, yeah. And also … Fleming was able to quit his job, a central tenet of every musician’s wildest dreams. He credits “Nashville latching on to The Vandoliers,” but he also says it was his wife’s idea. And in truth, it’s probably the decision he’s been trying to make for half his life.

“For me, my path, even though I’ve tried to avoid it by going to barber school or audio engineering school, trying to find a logical thing to subsidize this other thing that I’m driven to do, it’s writing songs. It’s the only thing I really think I’m good for. And whether that makes someone jealous or dislike me for being ambitious about what I want to do, that’s up to them.”

That’s another thing about Fleming. As much as he is a talker (or storyteller, if you prefer) he is even more ambitious. But that’s part of why he’s on tour from the spring until the fall to promote The Native.

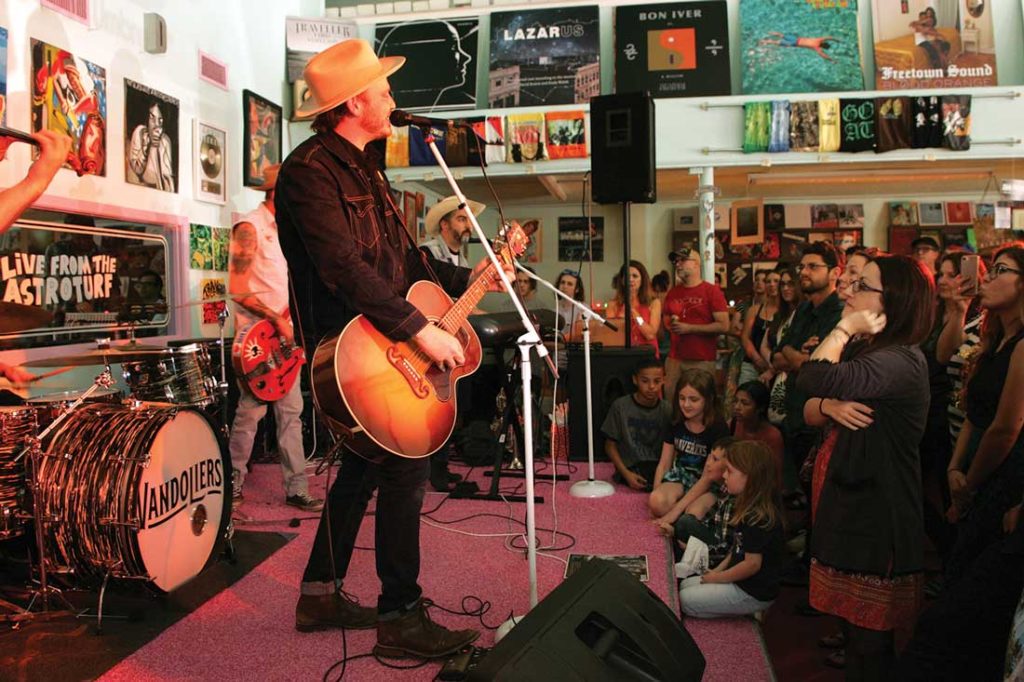

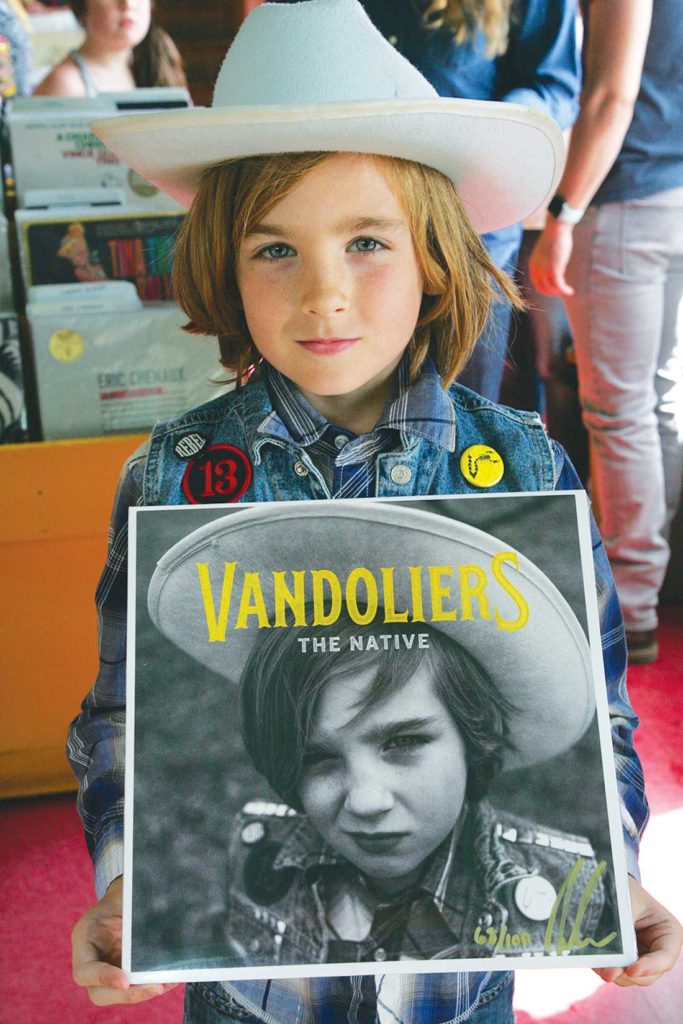

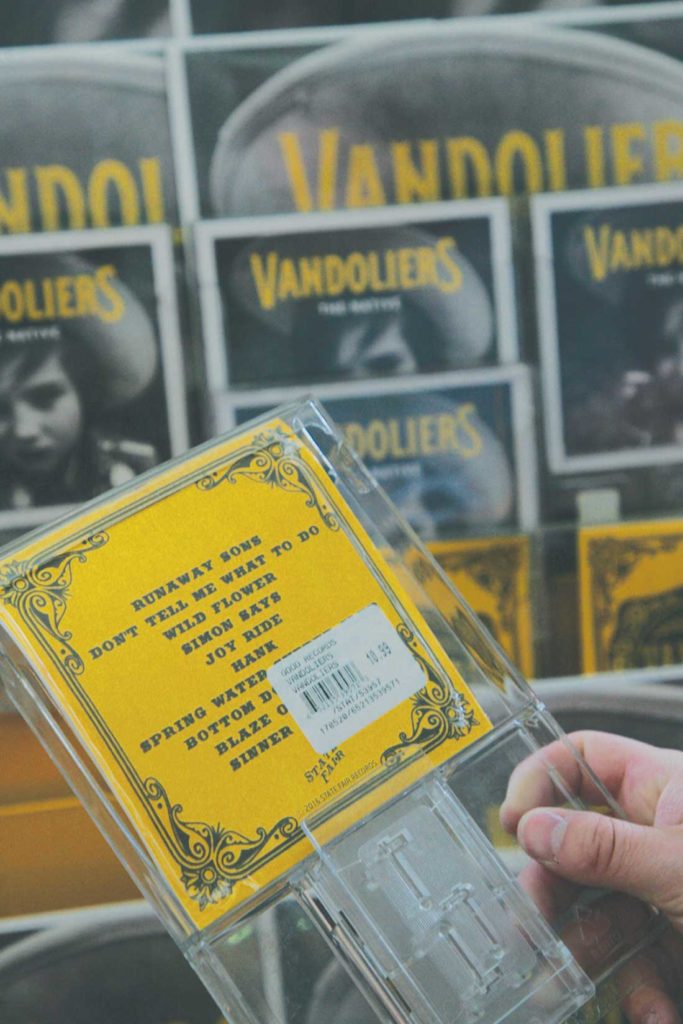

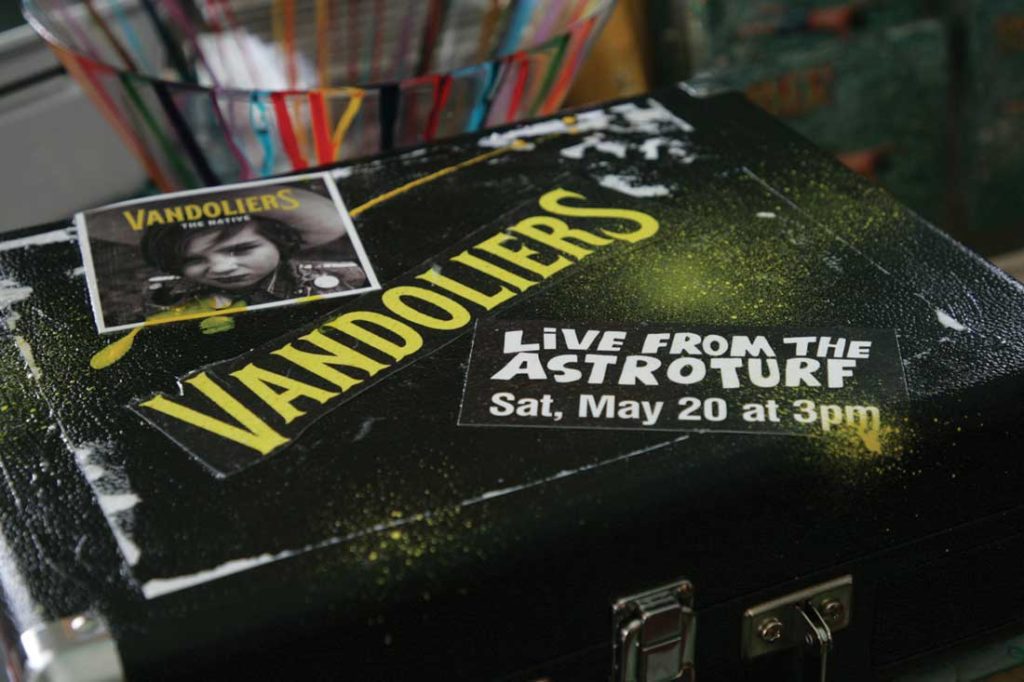

Recorded at Audio Dallas in Garland (itself famous for being the studio where Willie Nelson recorded Red Headed Stranger when the place was called Autumn Sound Studios) and mixed and mastered by Wes Sharon and Eric Conn of Turnpike Troubadours fame, The Native is a 10-song LP (released digitally and on vinyl this week) of Fleming’s semi-autobiographical stories that are as Texan as the day is long and August is hot – the opening track is called “Bluebonnet Highway,” for example. But they’re also shot full of punk rock energy, as well as Tejano and even Cajun influences, courtesy of bandmates Travis Curry (fiddle), Dustin Fleming (guitar), Cory Graves (keys, trumpet), Mark Moncrief (bass), and Guyton Sanders (drums). In doing so, Fleming has crystalized just about everything he’s ever attempted with his musical experiences, from the Joe-Ely-and-Mike-Ness-soundtracked drives to the coast with his dad to the horn parts that punctuated The Goners’ nuttiest sounds and the rowdy party that happened at a lot of Phuss shows.

“The Native is easily the best music I’ve ever done,” Fleming said. “From beginning to end, it’s introspective about me growing up as a person, but in the middle there’s barhopping – I got to write a song about Pantego and getting arrested there – and how I got to be interviewed in Rolling Stone.”

But he also credits his band for teaching him more about country than he knew already, telling me anecdotes about how grateful he is to have learned from such a talented crew of musicians. If nothing else, Fleming is always willing to learn and adapt. But he feels like he’s finally found his place in the world with The Vandoliers, which is kind of funny since his band is basically the story he’s been telling all his life.

I saw the Vandoliers about two weeks ago. They are the best band I’ve seen in a long, long time. Do yourself two favors. Buy their CDs and see them live if you can. They wail!