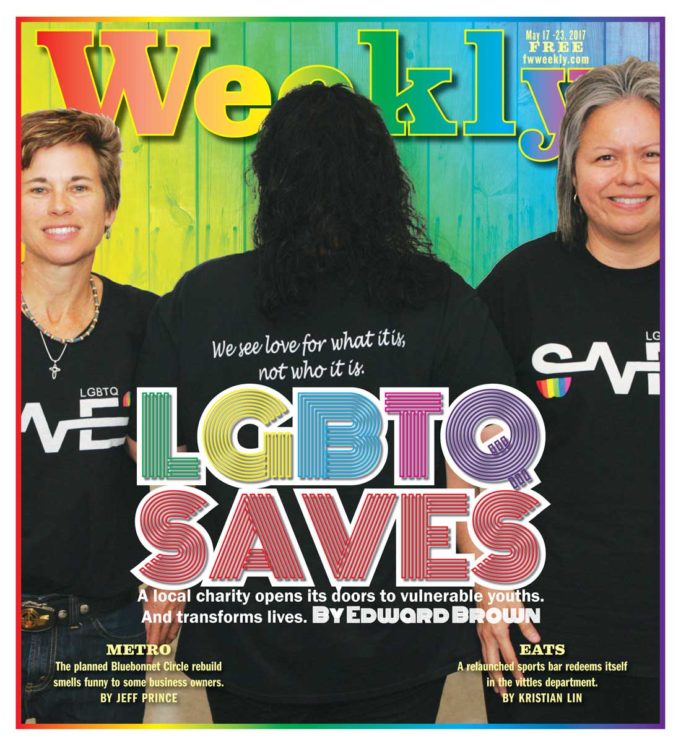

The young boy fidgeted in response to the question. Sitting in a large room at an Eastside church recently, he was among a dozen other children and teenagers introducing themselves to one another as part of a regular meeting hosted by LGBTQ Saves, a seven-year-old Fort Worth nonprofit that provides mentors and support for LGBTQ youth.

Lisa Earley, an LGBTQ Saves youth leader, had asked, “What’s your preferred gender pronoun?”

The boy said it was his first time at a meeting like this. “I’m pretty nervous,” he added.

Several nearby kids offered words of support, encouraging him to go on.

“I’m gay,” he continued. “My preferred gender pronoun is ‘he.’ ”

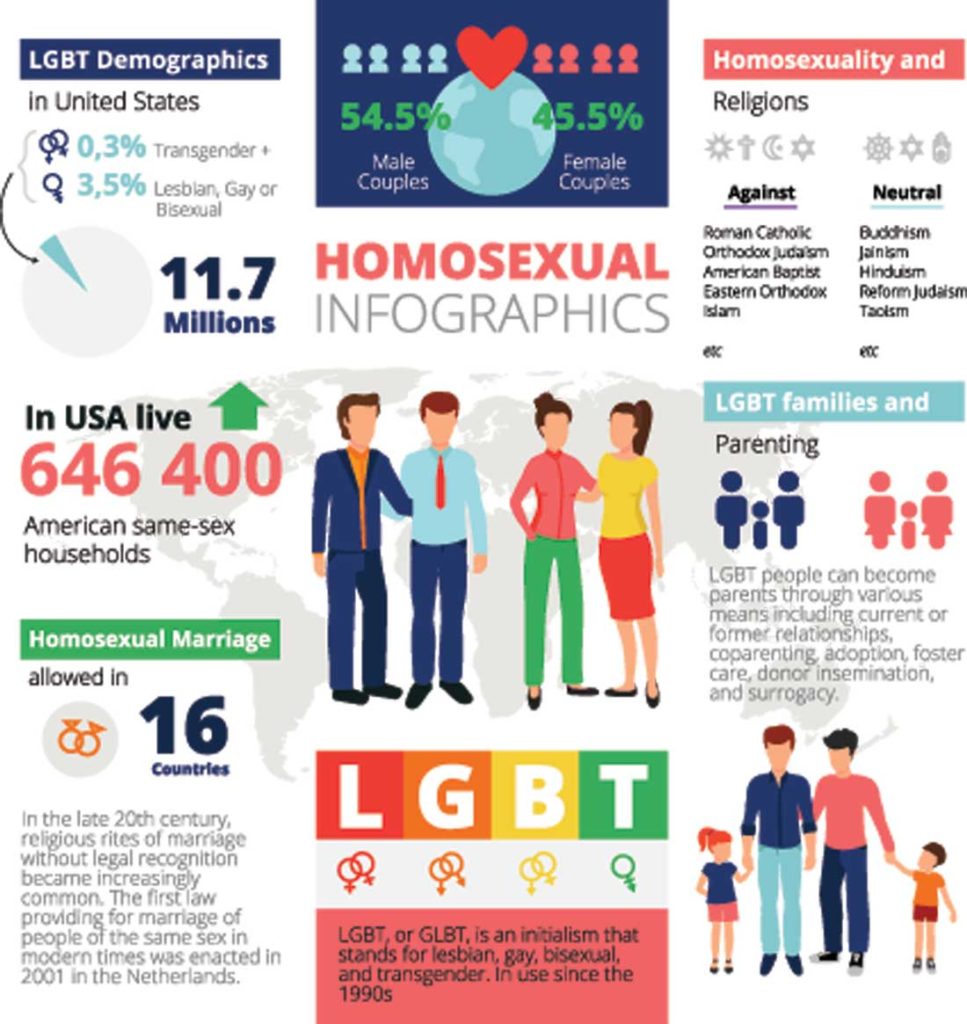

After the introductions, the discussion turned to topics ranging from definitions of terms like “transgender” and “bisexual” to advice about how to come out to relatives and friends.

Nearby, several LGBTQ Saves board members held a meeting, discussing and planning upcoming events. Heading the board meeting was LGBTQ Saves’ founder and president, Sharon Herrera.

Nearby, several LGBTQ Saves board members held a meeting, discussing and planning upcoming events. Heading the board meeting was LGBTQ Saves’ founder and president, Sharon Herrera.

By hosting the meetings at churches, Herrera said, parents are less likely to question the nature of the gatherings, noting that some of the children have not come out to their parents and relatives.

The youth meetings, originally held on Herrera’s back porch, are nearly as old as the group itself. LGBTQ Saves moved to its current location two and a half years ago, when Herrera was alerted to a large contingent of teenagers who were attending meetings by the adult support group PFLAG (Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays), which has held meetings at the same Eastside church, First Jefferson Unitarian Universalist, for 25 years.

As the recent meeting continued, the kids traded stories about their experiences coming out to friends and family.

“Don’t go fast and tell them you’re” transsexual, one curly haired curly-haired teenage girl advised. “Then you get thrown out of the house like I was.”

“The people who need to know will know,” an older teenage boy interjected. “The people who don’t care don’t need to know.”

“I came out to one of my coworkers,” said a teenage girl with short dark hair. “We were talking about dating life. I started saying, ‘I talked to this chick one time.’ My coworker said, ‘So how do you identify?’ You don’t have to come out and introduce yourself as being gay. It could be little things. Then they ask.”

“Be safe when you come out,” Earley said. “What would happen if you’re not out but you’re having [gay relationships] and someone outs you? You may need to think about a close friend who would be hurt if you don’t tell them first. You have to think about that side as well. Again, whoever you tell, it’s your choice. I would recommend coming out slowly.”

As the meeting concluded about an hour later, Earley offered more encouragement.

“The people in this room are here for y’all, and that’s a big deal,” she said. “Anytime your parents have questions, PFLAG has lots of resources. Even if they won’t come to these meetings, expose them slowly. Sometimes they will come around [to supporting you], and sometimes they won’t.”

LGBTQ Saves is now a full-fledged charity that connects LGBTQ students across North Texas with one another through online forums while providing mentors to lend a caring ear. One longtime dream of Herrera’s is closer than ever: Plans are in the works with a local church to provide a permanent space for her group.

“My vision is to have a drop-in center that’s open [from] 3 to 9 [p.m.] Monday through Friday,” she said. “It’ll be a place that provides mentoring, family dinners on Fridays, job training, and whatever the child needs to be successful.”

Countless youths are helped daily by Herrera, who works for the Fort Worth school district as a student engagement specialist and volunteers with numerous nonprofits. Those closest to her know her passion for helping kids stems from her conflicted childhood and her own difficulty coming to terms with being gay.

*****

As a child, Herrera, who now is openly gay, had no one to turn to when reckoning with her homosexuality. An affirming, progressive hometown might have spared her the torments of her childhood, she said.

In the late 1970s, San Angelo was not that town.

Complicating matters was the conservative Catholic environment in which she said she grew up.

At church, Herrera was told homosexuals go to hell. In the broader community, there were no openly gay role models she could speak to.

At 16, she decided drinking a bottle of Drano was preferable to her conflicted identity. Her suicide attempt was thwarted when her aunt walked in on her moments before she put the cleaning agent to her lips.

“I know, mija,” Herrera recalled her aunt Margaret telling her. “You don’t like boys.”

Those seven words, Herrera said, probably saved her life.

Her aunt kept her secret until Herrera was ready to come out four years later. She found her family to be surprisingly accepting.

After graduating from Angelo State University and then Amberton University, Herrera served for four years in the U.S. Air Force as a financial services specialist, eventually attaining the rank of Staff Sergeant. After her service, the first half of her career was in the private sector in human resources. Herrera’s job as a loss prevention specialist at H-E-B Grocery Company in Austin abruptly ended in 2000 when she was seriously injured in an automobile accident. A driver ran a red light, t-boning her truck and leaving her with a major head injury from which she has since recovered.

During her months-long recovery, two aunts in Fort Worth encouraged her to move to their city.

“I never imagined I would live in a city called Cowtown,” Herrera said with a laugh.

Her relatives encouraged her to consider substitute teaching while looking for work. Even though her professional career had been in human resources, she gave it a shot.

“That was my first experience teaching,” Herrera said. “In less a year, you can light the life of a child or [let them down] if your heart is not in it. Teaching, for me, is a matter of preparing students to be self-sufficient.”

In 2006, after teaching kindergarten for three years and third grade for two years in the Fort Worth school district, Herrera transitioned to another position within the district, this one as an investigator for faculty discrimination and harassment. In 2011, she took her current position.

About a year earlier, several much-publicized LGBTQ youth suicides across the United States stunned her. The uptick prompted President Barack Obama to release a video aimed at comforting bullied teenagers. LGBTQ students, based on a 2008 study by the federally funded Suicide Prevention Resource Center, are upwards of several times more likely to attempt suicide than their heterosexual peers.

The 2010 events, Herrera said, reminded her of her own suicide attempt decades earlier. Always feeling guided by a higher power throughout her life, she believed something had brought her to Fort Worth and to her job working with LGBTQ youth.

Herrera found that many LGBTQ youngsters in the Fort Worth school district were homeless or relying on friends to provide a place to sleep.

Clint Bond, communications director for the Fort Worth school district, said in an email that 1,558 district students currently report their status as homeless. Herrera said many of them were forced from homes because of their sexual orientation.

“I asked myself, ‘What am I doing to help?’ ” she said.

Herrera was surprised to learn that Fort Worth didn’t have a program dedicated to supporting LGBTQ youths at the time.

“We were brainstorming what event to have first,” she said. “The first thing we thought of was a Winter Prom.”

Herrera organized the prom for 27 LGBTQ youths at Celebration Community Church on the Near Southside with the help of several civic leaders, including Thomas Anable, founder of Fairness Fort Worth, a nonprofit that advocates for the fair treatment of LGBTQ individuals, former Police Chief Jeff Halstead, and Celebration’s Rev. Carol West.

Those early years involved a lot of “work, sweat, and money out of our pockets,” Herrera recalled.

Karin Grassl-Petersen, a Fort Worth school district teacher and LGBTQ Saves board member, began volunteering around that time. Grassl-Petersen had asked Fort Worth school directors about the extent of the district’s inclusive policies regarding LGBTQ students. They referred her to Herrera.

There was strong community interest in Herrera’s vision from the get-go, Grassl-Petersen recalled.

“People were interested in what we were about, different ways they could help, and what issues and roadblocks we were facing,” she said.

Some of those roadblocks, she added, included finding venues to host events, reaching LGBTQ students, and sustaining LGBTQ-friendly programs in a conservative community.

“We have seen an amazing outpouring of commitment to LGBTQ youths,” she said. Churches, artists, and musicians have all “held fundraising events in our honor. We look forward to expanding our abilities in outreach and meeting the needs of the LGBTQ youths.”

That October, Herrera and several volunteers organized Teen Pride, held one week before Gay Pride Week. The youth-led parade drew seven kids the first year, Herrera said. Now the event draws more than 100 youths. The following month, Herrera named her group LGBTQ Saves.

The glue that holds LGBTQ Saves together is the schedule of bi-weekly meetings at First Jefferson church. The gatherings are largely student-led, Herrera said. Word of mouth and the help of volunteer groups within public schools such as Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs) are the biggest resources that Herrera’s group uses to draw kids to the meetings and other events.

“We get kids from Keller, Mansfield, Weatherford, all over,” she said. “It’s not just” Fort Worth school district students.

The equal treatment of LGBTQ students in Texas’ public schools remains a battle. One year ago, Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick visited Fort Worth school district headquarters to lambast the transgender student guidelines that allow students to use the bathroom of the gender with which they identify. In a press meeting tirade, Patrick invoked the term “social engineering” several times when referring to the school policy. More recently, Patrick, with the support of Gov. Greg Abbott and several high level state officials, pushed for a state bathroom bill that mandates people use public restrooms that correspond to the gender listed on their birth certificates. The controversial bill, which many say will harm business, has until May 29 to reach the governor’s desk. Amid a hostile political climate, Herrera and her volunteers soldier on.

The advent of social media apps like Facebook and Snapchat has added another tool for LGBTQ Saves to reach vulnerable youths, Herrera said, adding that she encourages kids in her program to exchange phone numbers with one another so they have a readily available support network.

A new scholarship to encourage “responsible social skills and advance academic studies” is a program the nonprofit began offering this year.

“This has been a major goal of ours for quite a while,” Grassl-Petersen said, adding that each scholarship will range from $250 to $2,500, depending on available funds.

With the help of Herrera and others, many former LGBTQ Saves youths have overcome troubled childhoods and are now flourishing as young adults. Several of them now volunteer and mentor for the nonprofit.

*****

One former LGBTQ Saves student and current mentor, who asked to go by Papi, is enrolled at Tarrant County Community College. She said she was immediately attracted to Herrera’s warmth and openness. They met at a youth meeting at Paschal High School.

Herrera, Papi recalled, “spoke about her organization. I could tell she cares about everyone she meets.”

Only days before that meeting, Papi said she attempted suicide after being outed by a relative during a family argument. Her parents made it clear they weren’t ready to accept a gay daughter. Though Papi did not want to go into detail, she said she tried to go through with it but that it “went bad.”

A school youth leader encouraged Papi to attend one of Herrera’s back porch meetings. She immediately felt at home.

“For the longest time, I felt I didn’t have a purpose,” she said. “I heard other kids’ stories. Many of their experiences were rougher than mine. It completely changed how I thought. They were handling their situations very well.”

She paused.

“I thought, ‘This is why I didn’t die,’ ” she said. “I’m meant to be here.”

Papi said she keeps in touch with the friends she’s made through LGBTQ Saves. Occasionally, someone will text her. They all have similar refrains: “Hey, can we talk? I’m having a bad day.”

More recently, Papi said, her parents have accepted who she is. She credits Herrera with helping turn her life around.

Another former LGBTQ Saves youth, Alex Loesch, plans to work for Herrera when the drop-in center opens. The 21-year-old said his goal is to be the “voice” between adults and youths. While technically an adult, Loesch is young enough to still feel the years of bullying and harassment he endured throughout middle and high school.

Photo: Istock.com

“I came out when I was 12,” he said, referring to his self-identity as bisexual.

Loesch, who had a girlfriend at the time, found solace online, where he could chat openly with people who were far less judgmental than his schoolmates.

His grandmother, who raised him, was loving and accepting, he said. Life at school, however, wasn’t nearly as forgiving.

A close friend outed him to his seventh grade class, he recalled, presumably upset at his intimate online conversations with others.

Cruelty knows no bounds in middle-school social circles. Loesch said he was banished from his normal lunch table and relegated to a sixth-grade table with two other outcasts. Jeers of “faggot!” greeted him between classes.

“You get used to it,” Loesch said, shrugging, trying to brush off the memories that are noticeably painful even now.

In eighth grade, he participated in the National Day of Silence, a commemorative event every April 15 to remember suicides by youths who were gay or perceived as being gay.

“That was a time when several kids had committed suicide in the area,” Loesch said, referring to the same period that spurred Herrera to found her nonprofit. “I commemorated their memories by staying silent.”

Loesch recalled that his English teacher mocked his decision in the middle of class, adding that homosexuality was immoral.

By high school, years of harassment and verbal assaults from his classmates became too much to bear. At age 14, he had the police called on him by the parent of a friend after finding text messages from Loesch in which he described his intention to drown himself. Loesch was committed to Sundance Center Fort Worth, the behavioral health ward at John Peter Smith Hospital. Loesch admits the intervention probably saved his life.

“I couldn’t take it anymore,” he recalled of that dark time.

His grandmother searched Fort Worth and Dallas for a program that could help her grandson recover from years of bullying. On his 15th birthday, the summer before his junior year of high school, the search led to Herrera, who was working for the Fort Worth school district as a district mediator.

From that moment, Loesch said his life slowly began to turn around. Herrera introduced him to other mentors who would become as close as family, including pioneering LGBTQ community leaders Anable and David Mack Henderson.

As our interview came to a close, Loesch checked the time. A LGBTQ Saves Youth Meeting was about to start. As his thoughts turned toward the night’s event, he brightened up.

“Now [LGBTQ Saves] has some money, and everything is falling into place,” he said. “I’m excited about it. I have to do my part to make this world a better place.” l

What a powerful story! Where can I donate to LGBTQ Saves?

http://www.lgbtqsaves.org/donate.html

Sharon is an incredible woman with heart and strength. Sharon is someone to look up to when you think it can’t be done. Her program is saving lives and I hope more people understand her goal is to save the lives of children/teens/young adults. Godspeed my friend!

ask her who Rebecka is? and that will tell you what a wonderful heart she has.

“By hosting the meetings at churches, Herrera said, parents are less likely to question the nature of the gatherings, noting that some of the children have not come out to their parents and relatives.”

So, they use subterfuge to hide from parents what children are being subjected to? Typical of the homosexual agenda. They’ve been lying to us for years what they are really about.

Do these minors have their parents’ informed permission to attend these organizational meetings? If not, this smacks of illegal usurpation of parental authority.

So many screwed-up people. Oh, and yes, I’m right, and all of you are wrong.

Peckerwoods can be expected to behave as Peckerwoods…..what’s new here?

Do these parents have informed permission to be hammer-headed half-wits? Hooray for me, screw you,,,, kiddo! Jesus was not a hammer-headed Republican,,, see?

Hello, I’m not here to bash anyone but…..At one time this Sharon Herrera considered me a child of hers……even considered adoption at one time. She was married to my mother for 16 years. She disappeared without a trace and I just didn’t have a step-mother anymore. I am glad she is helping other kids and teens but I cant help but wonder what happend to my “mom”?!?