Rod Nippert grew up on a farm with 40,000 turkeys in the Appalachian Mountains in Southeastern Ohio. He wanted to escape the life of a farm boy as quickly as he could. Nippert had big plans – become an engineer, move to the city, and buy a red Corvette. That was 1967. Forty years later, he and wife Linda live and work on a 100-acre community-owned raspberry farm in Appalachia. He spends his days puttering around in a stained-glass shop that he runs with his neighbor. There’s no Corvette in his garage. Nippert’s life was fundamentally altered by his decision to break the law. He hasn’t paid his federal income tax, in full, since 1973.

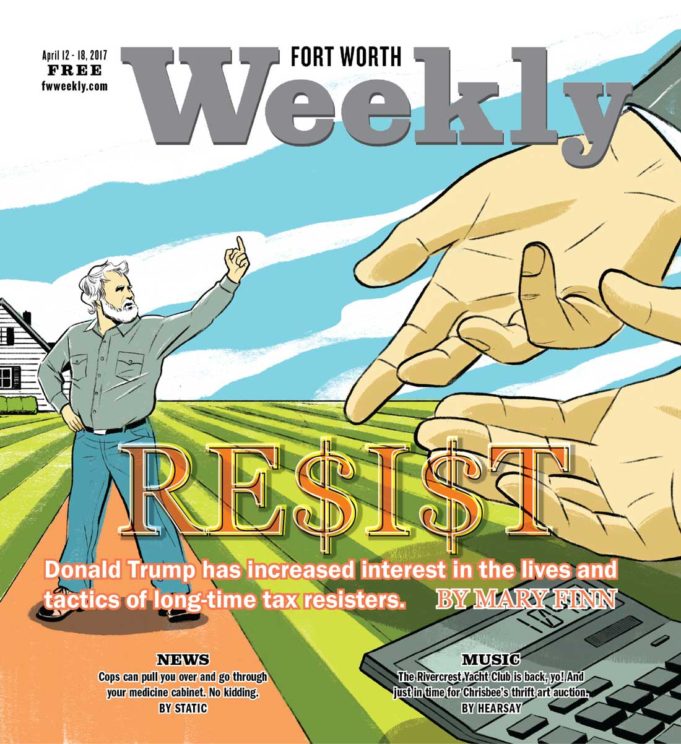

Nippert is one of approximately 8,000 Americans who openly choose to contest paying their full federal income tax owed to the government. They don’t consider themselves to be criminal tax evaders. They prefer to be called “war tax resisters.”

President Trump’s refusal to release his income taxes has fueled interest in tax resistance for some anti-Trumpers. “Take a look at Trump,” says Jay Sordean, a war tax resistance pro bono counselor in Berkeley, Calif. “Did he reveal his taxes? No. I am sure he is hiding lots of crap. He is in this for himself, and I am sure his taxes reflect his beliefs.”

But for long-time resisters like Nippert, the decision not to pay taxes doesn’t depend on who is in the White House. It is a matter of personal conscience.

As a child, Nippert had attended services at the Church of the Brethren. “When I was a kid, I knew my religion and stuff, and I was involved in a youth group, but I didn’t think too heavily about what was going on in the world or what that had to do with my religious beliefs,” he says. “I knew things were going on in the world, but they didn’t seem personally relevant.”

But as with so many others, the Vietnam War created a moral crisis for Nippert. He was lucky to get a draft deferment from the war by enrolling as a student at Ohio University before transferring to The Ohio State University. The war plodded along, and Nippert lived a parallel life as a Buckeye. He pledged a frat, but the brothers decided he wasn’t Beta Theta Pi material.

“Looking back on it, I think they made the right decision,” he says. “That was a time when everything was changing. I was letting my hair grow a little longer, but the frats were still pretty conservative. There were weird things they didn’t like about me. I didn’t hold my cigarette the right way. And you know, really, I was just a farm boy.”

Around the same time, someone gave him a copy Joan Baez’s memoir, Daybreak.

“Her book affected me a lot in terms of thinking about issues of pacifism and made me think about what I learned about non-violence from Church of the Brethren,” he says.

In 1968, Nippert started hanging out at political meetings at Ohio State, where he learned more about draft resistance and non-violent protest. “I grew up being taught to think for myself, and once I started going to meetings and hearing people talking and hold strong opinions passionately, it kind of opened me up,” he says. “It caused me to ask, ‘What do I really believe in passionately? How am I supposed to live my beliefs?’ ”

Initially, he became involved with a campus group that was doing draft counseling for people who wanted to escape to Canada and helping them fill out forms so that they could register as conscientious objectors. But Nippert’s own conscience continued to gnaw at him.

One night in 1969, he broke into “The Shoe,” Ohio State’s 66,000-seat football stadium. It was midnight. He climbed all the way to the top bleacher and sat there, alone, for a few hours. Enveloped by the all-American scene, Nippert thought about his relationship to his country.

“I wanted to make the right decisions,” he says. “I am not, and never have been, anti-my country. Not at all. I love my country. I thought that if I am not truly a pacifist, I should go register for the draft and serve. I am not going to walk around saying I am a pacifist if I’m not willing to make a personal sacrifice. I am not a chicken. I can’t be just trying to get out of going to war. I have to really be for something. Sitting up there in the stadium alone, I came to my decision. I decided that I couldn’t kill anybody.”

But there was more.

“If I can’t kill someone, can I pay someone else to kill for me?” he asked himself.

“I decided that I couldn’t do either, and I really needed to live as a pacifist.”

Two months later, Nippert dropped out of Ohio State and was called up for the draft. The draft board required documentation to validate his conscientious objector status. Nippert had brought with him a letter of support written by his father, who had been a fighter pilot in World War II and was captured and starved by the Nazis as a POW. In the letter, his father wrote, “As a farmer, we learn that each of us needs to plow our own furrow.”

Nippert’s petition was approved, and soon after he stopped paying his taxes.

War tax resisters believe that we should be able to decide for ourselves when, if, and how much we pay in federal tax based on our beliefs. They think we should be able to decide how much we pay, or if we pay at all, when we don’t think the government is going to use our money to our liking.

The IRS clearly does not agree. Though the Internal Revenue Service did not respond to our questions about tax resistance, IRS Code 6702 requires the agency to maintain a list of “frivolous filings,” which, according to the agency, “describes and responds to some of the common frivolous tax arguments made by those who oppose compliance with federal tax laws.” The IRS can fine a filer up to $5,000 for attaching a letter of protest or writing directly on a tax form about any of the frivolous filing issues. War tax resistance is on the list.

“One doesn’t like to hear the word ‘frivolous’ about an action we take so seriously, but I know it isn’t intended as a diss to us in particular,” says Ruth Benn, the national coordinator of the National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee (NWTRCC, pronounced “New Trick”), a group founded in 1982 in response nuclear proliferation. “Since they started the frivolous filing penalties as a result of war tax resistance, a lot of us did an action we called ‘cabbage patch filing.’ People filed dozens of 1040s instead of filing just one. The goal was to slow down the system.”

One person’s frivolity is another’s necessity. Kesh (who asked to be identified by her first name only), a 38-year old Baltimore service industry worker, didn’t pay taxes last year because she couldn’t afford it.

“Because I couldn’t afford to pay for my insurance last year, they charged me a penalty for that — a penalty for being poor,” she said of the fine she would have to pay for not having health care under the Affordable Care Act.

Then she started to wonder where the money went.

“I know that my tax money is going to the police, and I can walk down the street and get shot,” she says.

Though local police forces are primarily funded through local and state governments, police departments do receive some federal funding. And as an African-American woman in Baltimore, where Freddie Gray’s death in police custody in 2015 led to a police curfew enforced by the National Guard, Kesh was more concerned about the militarization of the law officers in her neighborhood than a far-away war.

Trump, she says, made all of this worse. “I’m all the groups that are hated,” Kesh continued. “I’ve decided to come to earth in this body and be black, be a woman, gay, so you know, I get hit on every side of it. I was a teenaged mother. I’m a single mom. I’m all the things [Trump and Republicans] hate.”

Unlike the other resisters, Kesh is new to this. She doesn’t know where it will lead her yet, hence her decision not to use her name. She has not taken workshops or been formally advised, and she is at risk of being targeted by the IRS.

So it is difficult to think of anyone’s decision to defy one of our fundamental civic duties as frivolous. But even some tax resisters think this way.

“Some people who don’t pay taxes are just fruitcakes in terms of the reasons they are using to avoid paying taxes,” says Peter Smith, a war tax resister from Indiana. “You know, like things that are never going to work.”

For instance, there are some people in the states’ rights crowd who believe the 9th Amendment protects them from the overreach of the federal government’s ability to collect income tax. For some odd reason, some filers claim that if they write the phrase “nunc pro tunc” on their 1040 form, they won’t have to pay income tax.

“But the people who are out there who are honestly conscientious objectors and have legitimate reasons, we respect them and we say, ‘Go for it,’ ” Smith says.

Some people, for instance, refuse to pay their first $5,000 in federal tax because of what they refer to as a “Black Tax,” a version of self-imposed reparations taking the place of the 40 acres and a mule promised by General Sherman at the end of the Civil War.

Still, military spending is the most common issue. NWTRCC publishes an annual analysis of the federal budget in which the committee determines that about 50 percent of the federal budget goes toward current military spending, debt on past wars, upkeep of the nuclear arsenal, and funding for homeland security. War tax resisters, like Nippert, use this figure as a guidepost when paying (or not paying) their federal income tax. But under Trump, military spending is poised to spike.

“Interest in tax resistance has been unusually active because of Trump’s election,” NWTRCC’s Benn says. “We saw a huge jump in our web stats since the inauguration. It is tax time, and we have a president we don’t like. I mean, we aren’t like the Women’s March with hundreds of thousands of people coming out. But, around the country, we are finding more interest in our workshops where there will be 20 people attending instead of the usual two. Local networks that don’t usually contact us have been unusually active. Some of the groups out there who are anti-Trump have come to us for ideas.”

While the current political climate may have created a spike in interest in war tax resistance, many war tax resisters interviewed for this story made it clear that their opposition isn’t grounded in partisanship but is based on a life of pacifism inspired by flashpoints like the Vietnam War, the 1980s nuclear arms race, American military involvement in Central America, and the more recent wars in Iraq.

Like Nippert, resisters tend to start out as activists and protesters in anti-war movements, and then, ultimately, they ask themselves, “If I am so against war, then why am I paying for it?”

“These are all conscious people who have chosen to stay out of the system,” Benn says.

Smith, the war tax resister from Indiana, served in the military for four years in the early 1960s. “During the Vietnam War, I knew that what the government needed to fight the war was money and people,” he says. “I knew that I could resist with my money, and so I did.”

For others, the catalyst was even more personal. Peace activist Cindy Sheehan, best known for her month-long 2005 tent encampment outside President Bush’s ranch in Crawford, Texas, lost her son Casey to the Iraq war in April 2014 and stopped paying federal income tax.

“After Casey was killed in the Iraq War, I looked at my then-husband and said that is the last time I am paying taxes,” she says. “I am not filing or paying taxes to this government because they took something from us that they can never repay. For years, I had funded the murder of so many people, including my own son.”

She has ongoing federal liens against her for any future assets she may acquire, but the magistrate in her IRS hearing took a sympathetic stance. “The judge looked up at me at the end of the hearing and said, ‘What you’ve done sounds like a real reasonable response to something that happened to you that was so unreasonable,’ ” she recalls.

Many tax resisters view what they do as a reasonable response to an unreasonable situation. But the 8,000 war tax resisters don’t necessarily believe that they will stop all war. Not anymore, at least. Most of the people I spoke to for this article are now in their late 60s. They started their resistance wide-eyed and bell-bottomed, intending to starve the “war machine.” Now, most admit that’s not going to happen.

“I don’t want to totally give up on change, but I don’t expect it in my lifetime,” Benn says. “What we do is going to someday turn things around. Like any conscientious objector, I think I have a role in showing another way. Through my tax resistance, I am trying to show what is important.”

War tax resistance is idiosyncratic. There isn’t a prescribed way to do it. Resisters do all they can to make it difficult for the IRS to collect what is owed. But for most, being a war tax resister translates to creating a simple, asset-free life.

Nationwide, NWTRCC-affiliate groups offer counseling to those interested in committing war tax resistance. Participants are guided to reflect on what they believe and to articulate what they are looking for from their resistance. Then they commit to the course of action that is the best for their life situation and their tolerance for risk.

Jay Sordean, the volunteer war tax resistance counselor in Berkeley, is self-employed and doesn’t have withholdings taken directly from his paycheck. He also lives below the taxable income limit. Sordean files his 1040 tax form every year, but he doesn’t include a check. He sends a letter of resistance with his form.

In the 1990s, he got creative and sent palm-sized helium canisters that “looked like little cruise missiles” attached to his 1040, along with a letter of protest to the IRS, his senators, and the Clinton White House. (Warning: Don’t try this in the post 9/11 era.)

War tax resisters who do receive a paycheck often hike up their withholding exemptions and end up having little or no money taken from their pay. Some people file, withhold $10.40, and attach letters demanding a decrease in military spending, in an act of what is referred to as “symbolic resistance.”

Like many resisters, Nippert put all of his assets in his wife’s name so that their house can’t be seized by the IRS. He doesn’t make enough money on the raspberry farm or in the stained-glass shop to pay personal income tax.

Every war tax resister I talked to donates the money that should have been paid in taxes to either charities or one of 50 funds that redistribute the money for “life-affirming purposes,” including the People’s Life Fund. Ann Barron, a resister since 2014 from San Diego, said, “I love paying taxes, but not for war. I pay my taxes, but not to the U.S. government.”

The war tax resisters view what they do as patriotic. The openly commit civil disobedience, spawned by a love of country.

Tax resistance isn’t easy. Most resisters live in fear and experience financial uncertainty. The IRS wants the money it is owed, and agents will do everything they can to get it, including placing liens on assets, seizing bank and retirement accounts, and garnishing wages. For many resisters, the hassle and risk is worth the sacrifice.

Tax resistance isn’t easy. Most resisters live in fear and experience financial uncertainty. The IRS wants the money it is owed, and agents will do everything they can to get it, including placing liens on assets, seizing bank and retirement accounts, and garnishing wages. For many resisters, the hassle and risk is worth the sacrifice.

“It’s been worth it for me,” Smith says. “One of the things about war tax resistance is that you have control over yourself. You can say no to the government, and that’s not something many people can do because they feel kind of forced into paying. It is empowering for me.”

Nippert doesn’t worry so much about the IRS coming after him. “If you can be sympathetic to the IRS, it is getting much, much harder for them to collect taxes even for big amounts of money because the federal government is giving them less and less to work with,” he says. “I know that I am low priority when they can’t even collect from people who owe a lot.”

Still, the collection letters from the IRS can be relentless and filled with intimidating legalese. “I get the collection letters, and they are a little scary,” Barron says. “One of the hardest things about tax resistance is that it is difficult to get the right legal information. My anxiety about the IRS was the first hurdle for me to get over in deciding to be a war resister. But now, I don’t feel fear. I made a decision to be public about what I’m doing. I feel a deep connection between what I believe and what I am doing.”

What about jail? In 1846, in the most famous case of war tax resistance, naturalist writer Henry David Thoreau was jailed for refusing to pay six years’ worth of back taxes because of his opposition to slavery and the Mexican-American War. Since then, only a few dozen Americans have been jailed for war tax resistance.

“Jail for war tax resistance is a myth,” NWTRCC’s Benn says. “The IRS doesn’t come and take you away. They just want their money. They don’t want people in jail.”

Tell that to Dr. Joseph Olejak. A chiropractor and natural healer from Chatham, N.Y., Olejak started withholding his taxes from the government in 1992. “At first, the letters came more frequently from the IRS, and the threats became more regular until eventually someone from the IRS showed up and said, ‘This is a civil matter now, but it will become a criminal matter if you don’t pay,’ ” Olejak recalls.

Armed agents ended up storming Olejak’s office and seized his computers and records. In 2013, he was sentenced to serve weekends in county jail because he owed $242,000 to the federal government. The charges against Olejak resulted in a felony conviction that caused him to lose his chiropractor’s license.

For 26 weeks, Olejak worked as a bookkeeper and advised clients on weight loss during the weekdays. On Friday night at 6 p.m., he checked into the county jail, changed into his jumpsuit, and was fed “food that was so disgusting you couldn’t even call it food. It was a concoction of soy-and-meat-like substance over noodles. It was so disgusting, sometimes I just fasted.”

He checked out of jail each Sunday night and returned to diet coaching. Any regrets about his choices? None.

“Somewhere, somebody is not going to have a smart bomb dropped on their head because I withdrew some money from the system,” Olejak says.

As part of his plea deal, Olejak agreed to pay taxes in $100 monthly installments when he has the income to pay and he was put on five years probation.

Aside from his highly aberrational jail sentence, Olejak suffered financial ruin. He can no longer practice as a chiropractor in New York because of his criminal felony. Still, he sees himself as successful. “There are all kinds of success,” he says. “There is ethical success and financial success, and the two are not necessarily the same thing. This is not something that happened to me out of the blue. I made the choice. I made a conscious choice not to participate in war. I accepted the consequences and hoped that they would not be awful.”

For Nippert, it’s turned out a lot better than “not awful.”

“I don’t have any doubts about what I’ve done,” he says. “I think probably my overwhelming feeling is that this isn’t a direction I would have gone on my own, but it’s really turned out to be great for me.”

Every morning, he walks the three-quarter miles to his glass shop with his dog Candy next to him. He spends his days in the shop listening to Emmylou Harris, the X Ambassadors, and Van Morrison. He and his wife, a recently retired elementary special education teacher, usually have an unfinished puzzle on the coffee table that they work on together in the evenings after dinner. They are grandparents to twin 4-year-old boys.

He’s got a birthday coming up.

“People ask me what I want for my birthday,” he says. “I don’t know. I mean, it’s not like I wish I had more money to buy more and more things. When I was younger, I wasn’t concerned with money so much. I was just in love with a ’vette, you know? But now, I’m just pretty happy. I am happy with the woods and my grandkids. I think the land is awfully healing.”

But his son married a woman whose family owns a local car dealership. They usually have a few Corvettes in the garage. Maybe he’ll take one on a drive for his birthday.

Mary Finn is a public school educator from San Francisco and a Freedom of Information Act researcher with Democracy in Crisis, a national column. With additional reporting by Brandon Soderberg.