Xander Berkeley strides onstage in front of a packed house. He inhales as if to speak but then stops.

“I forgot to read the play!” he thinks. “I forgot to learn my lines! How did this happen! Oh, my god.”

This never really happened, but the veteran character actor and native New Yorker knows the fear.

“I’ve had that dream I can’t tell you how many times,” he told me recently in a phone conversation from his home in Los Angeles, where he’s been living with his actor wife, Sarah Clarke, for the past 15 years. Berkeley has more or less called the City of Angels his home since the early 1980s, when he first broke into the film and TV biz. Most readers may recognize him from AMC’s science-fiction hit The Walking Dead, in which he plays the egotistical self-preservationist Gregory. Berkeley also has been in scores of TV shows and movies, including Hollywood blockbusters A Few Good Men, Air Force One, and Apollo 13 (and those are just the ones that begin with the letter “A”). Clarke struck gold as double agent Nina Meyers when 24 debuted in 2001, and she has appeared in numerous movies, perhaps most notably as Kristen Stewart’s mother in the juggernaut Twilight series.

Berkeley and Clarke are on their way to Fort Worth to star in an unusual play that requires actors to cold-read a script in front of an audience that has no idea what to expect.

“It’s a good thing I’m comfortable in scary spots,” Berkeley said. “This kind of qualifies as the actor’s nightmare.”

Theater critics describe White Rabbit Red Rabbit as a startling, completely original work. The Hollywood Reporter called it a “theatrical high-wire act.” The Associated Press hailed its “eye-popping experience,” while Entertainment Weekly noted how “the whole building felt like it was living and breathing.” The New York Times lauded Iranian playwright Nassim Soleimanpour’s seminal project as a “playful, enigmatic, and haunting solo show.”

That’s right. It’s a solo show. One actor. No idea what’s coming down the pike. No preparation. Then, go time.

A backdrop of war and house arrest sets the mysterious play into motion, but theatergoers are discouraged from doing any advance research since the element of surprise is reportedly crucial to the experience.

Amphibian Stage Productions will feature five different actors in five performances of the show on Wednesday, March 22 to Sunday, March 26. Berkeley takes the stage on opening night and Clarke on the second, both at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. The other three performances will be held at the Amphibian, featuring local visual artist and Fort Worth Weekly contributor Christopher Blay, War Party frontman Cameron Smith, and actress Christie Vela.

“It’s an education to see how different actors will interpret a character,” said Kathleen Culebro, Amphibian artistic director. “We don’t often get to see that.”

The play requires a new actor for each show. Actors who have tackled the role so far include John Hurt, Nathan Lane, Kyra Sedgwick, Martin Short, and more than 1,000 others in 20 languages around the world since Rabbit debuted in 2011.

Culebro expects the play to intrigue local theatergoers. She nabbed talented celebrities such as Berkeley and Clarke because of their longtime friendship with Fort Worth filmmaker and Amphibian Consulting Producer Tom Huckabee. And Culebro filled out the bill using three charismatic leads – including a painter and rocker – to attract customers who don’t typically go to the theater.

Clarke has been so busy raising two daughters and appearing in TV and movies for the past decade that she hasn’t done much live theater. But coming to Fort Worth to take the lead in an experimental play sounded like a challenge to the St. Louis native.

“Theater has always inspired me as a performer,” Clarke said. “This takes it to a whole ’nother level, and the unknown and the mysteriousness of it is thrilling as an actor, and terrifying. Anytime I find myself afraid, I feel like it’s something I should probably do. It means it’s touching something deep inside that is wanting to express itself.”

The most excited person of all might just be Amphibian’s artistic director.

“I will watch all five performances and just be in hog heaven,” Culebro said.

*****

Why would a couple of in-demand actors busy raising two young daughters while juggling movie and TV roles drop everything and travel from Hollywood to Fort Worth to headline an experimental play?

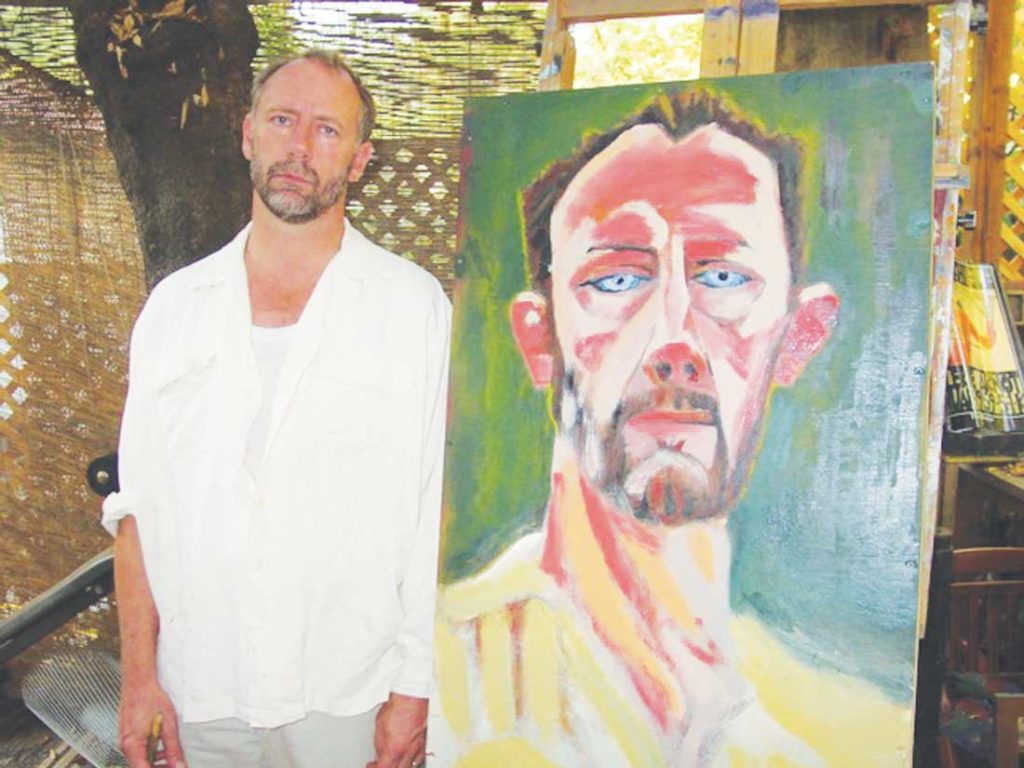

Turns out, Berkeley has more of a toehold in Texas than one might guess from his Big Apple roots, international persona, and La La Land life as an actor, painter, sculptor, mask maker, and makeup artist. Berkeley grew up in the Greater New York area, but his mother hailed from around these parts. Many relatives on his father’s side of the family settled in the Lone Star State as well. Berkeley made infrequent visits in his youth.

“I developed a real affinity for it,” Berkeley said. “I make sure I see my kin when I’m in that general vicinity.”

I called Berkeley on a recent morning and found him drinking coffee with almond milk while relaxing in his home studio, where he paints and sculpts when not preparing for acting roles. Clarke had soaked the almonds, removed the skins, blended them, and squeezed out the juice, he said.

“I’m in California, and we use almond milk instead of regular milk for our coffee now because that’s just who we are,” he said, mocking himself.

He turned out to be talkative, funny, entertaining, and tuned in to myriad topics. Almost immediately, the conversation turned to late actor Bill Paxton, the Fort Worth native who died of a stroke on Feb. 25 at 61.

“We are all still reeling,” Berkeley said.

Paxton, he continued, was “a force of nature, and he will be missed sorely, that’s for sure.”

Berkeley and Clarke last visited Fort Worth in 2007 when their movie Human Error was included at the Lone Star Film Festival. Paxton and Huckabee gave the couple a tour of the town.

“I particularly remember going to some place afterward where Harry Dean Stanton was playing music with some other people,” Berkeley said. “And we went to some other places. I loved it.”

Heading some other place is typical for Berkeley. Most of his early career was spent chasing acting assignments that took him around the globe. He was less interested in fame and fortune than travel and adventure. His training as an adolescent at the Black River Playhouse improvisational theater in New Jersey taught him more than how to emote and hit a mark. He learned to unleash his personality and to free his mind.

“When you are a teenager, the stranglehold of self-consciousness can really shape people in a very limiting way,” he said. “This group went out of its way to expand the repertoire of what you can do with your voice and body. It’s had a lasting impression on my experience as an actor on film.”

The training instilled in him something he refers to as the “Yes, and” mantra. Rather than saying, “No” during an improv routine, actors are steered toward saying, “Yes, and …”

“A lot of people’s initial instinct for improvising is to say ‘no’ to … go for the obvious conflict,” Berkeley said. “To avoid the deadening, stifling tendencies that that brings to an improvisation, they teach you to, in your head, say, ‘Yes, and,’ so that the improvisation can go somewhere rather than being stopped short.”

Berkeley took the training even further, making it his life philosophy. Instead of playing things safely, he dived headfirst into everything, from striking up a conversation with a stranger to accepting a part in a movie because it meant traveling to exotic locales. Berkeley’s roles carried him to Nicaragua during the Contra War and to Chile during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorial rule. The actor wanted to be embedded in the world rather than see it as a tourist. The “Yes, and” mantra “leaves you open in life to anything and everybody,” he said.

Paxton, despite his extensive filmology, frequently worried about when, how, or if he would get his next acting gig. He expressed this fear to friends, and he touched on them while speaking at the Lone Star Film Festival in 2015. Job insecurity stuck with him throughout his career as it does many actors. Berkeley’s mantra helped resolve some of those feelings.

“I’ve been at a great advantage because it was almost like I chose this as my spiritual path,” he said. “I never knew where my next job was, or if it was, or how much I was going to make, or for how long. I was going to have to be comfortable with the unpredictable.”

Berkeley’s father was an artist, inspiring his son early on to pick up a brush. Berkeley’s mother was a schoolteacher and seamstress. Berkeley loved reading stories and acting out skits, and he asked his mother to sew him costumes rather than to give him toys. The budding actor always looked the part when he pretended to be Robin Hood or Superman.

After college, Berkeley studied under private teachers from the Royal Academy of the Arts and the Moscow Arts Theater before moving to L.A., where he learned from legendary acting coach Lee Strasberg at The Actors Studio. Berkeley took small roles in big films, allowing him to learn on set from standout directors such as James Cameron (Terminator 2: Judgment Day), Clint Eastwood (The Rookie), Ron Howard (Apollo 13), Steven Spielberg (Amistad), and Rob Reiner (A Few Good Men).

Skills in painting, sculpting, mask making, and theatrical makeup filled in the holes between acting gigs. And he knew how to stick to a budget. He learned to keep a rein on his finances as a young man baling hay during the summers, and his acumen followed him into adulthood.

“I kept my overhead really low and never lived beyond my means,” he said. “I would hide money from myself, have a few different bank accounts, sort of tell myself I had less than I did so I could make it through whatever dry spells there were.”

The dry spells are fewer these days. Berkeley has several movie projects in post-production and is a consistent scene-stealer on The Walking Dead. The show’s black humor was one the primary attractions.

“As unlikely a vehicle for comedy as The Walking Dead is, I feel like I’m getting to do more comedy with this character than I’ve gotten to do,” he said.

Berkeley’s most life-changing gig, though, was 24, where he played George Mason for 27 episodes from 2001 to 2003. He met Clarke on the pilot episode. She was not quite 30. He was well into his 40s, a fleet-footed bachelor who had begun to think about settling down.

“I always felt like I was going to have to go back to New York to find my wife at some point, and then New York came to me,” he said.

Clarke was doing theater and TV commercials in New York when the producers of 24 hired her. Berkeley saw her on his first day and was smitten.

“She was from the Midwest, so that was different about her,” he said. “She was smart, beautiful, and talented. There was a scene where I got knocked out by a tranquilizer gun right off the bat. I was lying there in the room while she continued to do the scene, and I was very struck, just listening to her, by how good she was. You could hear it in her voice.”

She was new to town, staying in an L.A. hotel. She asked Berkeley where she might go to take a walk. He suggested a park and then tagged along. Afterward, they went to a party and hung out.

He was hooked.

“I felt for the first time in my entire life that I was done,” he said.

Berkeley wasn’t the only one feeling love pangs.

*****

Being an actor was an idea that Clarke toyed with in her youth but never seriously. Shy in school, she was hardly an attention seeker. Her career goal would become photography, perhaps so she could watch the world through a lens from a safe distance, a trained observer rather than a spontaneous participant.

She had studied dancing as a youth and even danced in high school plays but couldn’t see herself as the one commanding the stage with dialogue.

“I had a narrow view of what it meant to be an actor,” she said. “I thought if you were an actor, you were really outgoing and a showman. It didn’t translate to me that I could be an actor until, honestly, when I was in Italy.”

During her senior year at Indiana University, Clarke studied abroad in Italy. Walking around Rome and other cities, she worked on learning Italian and meeting new people. Her confidence grew along with her worldview.

“I started to understand my desire to be in the stories that I was documenting,” she said. “Even though I got a job in photography after coming back, it took me two years working in photography to sort of home in on the fact that I wanted to be an actor.”

One of her first jobs after college was photographing an art school in St Louis for marketing purposes.

“They couldn’t pay me, but they said, ‘You can take any classes you want,’ ” Clarke recalled. “They had an acting class. It was a great exchange.”

Clarke met someone in those classes who told her about Circle in the Square Theater in midtown Manhattan. Clarke wanted to study acting there but had to get out of her own way first.

“That was back when I really was afraid to go for what I wanted,” she said. “For me to audition and to decide that I wanted to move to New York was a big leap for me.”

She spent much of her 20s working in “Off-Off-Broadway avant garde theater.” One of those productions was slightly reminiscent of what she expects to go through in Fort Worth with Rabbit. She worked on so-called 24-hour plays whereby a theater group writes, casts, rehearses, and performs a show within 24 hours.

“It’s a pretty fast-paced situation,” she said.

Clarke gained industry attention after appearing in a Volkswagen commercial in 1999. She appeared in a couple of small films before auditioning and winning a part on a new TV series that debuted in 2001. Clarke spent three seasons and 36 episodes on 24 before her traitorous character was shot down. Clarke earned a Golden Satellite Award, given by the International Press Academy, for best supporting actress in a drama series.

During our phone interview for this article, Clarke got a big kick from hearing for the first time that TV Guide had named her No. 9 of the 60 nastiest TV villains a few years ago.

“No. 9? Wow!” she said. “I think the reason Nina was so devastating to so many is she was somebody they had put a lot faith in because they wrote her that way.”

Clarke went on to act in other TV shows and movies, including a small role in the under-appreciated coming of age drama Thirteen (2003). The movie didn’t do much at the box office, but Clarke’s talent caught the attention of director Catherine Hardwicke. Five years later, Hardwicke was directing the first Twilight and looking for someone to portray the mother of Kristen Stewart’s character, Bella Swan. She thought of Clarke because of the physical resemblance between her and Stewart.

“Even though I was a little young, Catherine really wanted me to play the mom,” she said. “At the time, I had a 1-year-old, and the thought of having a 17-year-old seemed strange to me.”

Clarke read the book and thought it was a “fun adventure for a teen girl” but had no idea that the movie would become the next big thing.

“The very first movie felt more like an independent film,” she said.

Four more movies would follow. Most of the massive public attention came from teens and tweens and was directed at heartthrobs Stewart and Robert Pattinson. Clarke got to enjoy the ride of being part of a “crazy phenomenon” without having the intense scrutiny that her younger co-stars endured.

Clarke might have enjoyed her role as Bella’s mother Renee, but certainly didn’t take away any parenting lessons. Clarke, in real life, would have been more hands-on.

“The whole role of the mother seemed so foreign to the way that I would mother,” she said.

A hands-on mother would have confined Bella Swan to her room or initiated a strict curfew, thereby reducing the chances that she would be off wooing vampires and werewolves.

“I couldn’t understand why I would be that removed, but it had to be that way,” Clarke said. “The story would have never developed if [Renee] had been like, ‘Quit seeing that boy!’ ”

Clarke, now caring for two real daughters, hasn’t seen Stewart in years.

“I’m all about the kids and schools now – I’m not really going out on the Hollywood scene much,” she said with a laugh.

The daughters came along after that chance meeting with Berkeley on 24.

While Berkeley was lying on the floor pretending to be knocked out from a tranquilizer that day, Clarke, too, was taking notice.

“I was immediately struck by Xander because of his presence and personality,” she said. “He really just stood out to me as someone who I would take seriously.”

Clarke was feeling uncertain and slightly overwhelmed by the trip to L.A.

“I had never worked in L.A.,” she said. “I had never been in a TV series and was just learning a lot about the medium of TV. Meeting Xander was a relief because he was so like-minded. I didn’t expect to find someone who shared so many of the same ideas and creative desires that I did. It was a reassuring thing to have him through that process because it was all so foreign to me, and he seemed very familiar even though I didn’t know him.”

Her admiration grew after watching his films.

“My respect for him was immense,” she said.

The 15-year age difference didn’t bother her.

“I was grateful that I was dealing with an adult,” she said. “Age doesn’t really apply when two minds meet that connect. When one starts to really examine [herself] in the way that actors do, age doesn’t seem the same. It is more about the spirit and energy of somebody.”

They’ve become each other’s favorite sounding board, which puts them in a strange situation for their trip to Fort Worth. Berkeley will handle the solo show the first night, meaning Clarke cannot see the play or even talk to him afterward. They will be staying in different hotel rooms.

“As acting confidants, we like to share each other’s experiences, and it will be tortuous not to be able to see his,” she said. “I want to be able to go in and do mine clear of any kind of preconceived ideas. They will be two very different evenings.”

Clarke admits to a bit of nerves but isn’t worried.

“This is intense in that we’re given the script right before we go on,” Clarke said. “But cold readings have been part of our training for years. When you are on set, you get pages that day so there is some bit of an understanding of what it is to pull something from a page and throw yourself into a world.”

The Amphibian seems the most likely of Fort Worth’s theaters to hop on Rabbit. The ’Phib, as it is sometimes called, has never been afraid to take chances, going all the way back to its inception as a basically unsupervised summer program at TCU in 2000. The theater department chairman “handed over the keys and said, ‘Take good care of it – you’ll have to replace anything you break – but have at it,’ ” recalled Culebro, who was a theater student at the time.

Unlike many start-up theater companies struggling in the basement of some old building, the ’Phib enjoyed state-of-the-art equipment, lights, stage, parking, and location. The company’s avant garde bent was evident early on, and it continued after the Amphibian moved to the Fort Worth Community Arts Center in 2008 after TCU began using its theater during the summer.

“We started learning how to be grownups and pay rent and do all those things you have to do,” Culebro said.

But the rent was higher than they’d hoped, the city of Fort Worth’s decision to charge for parking in the Cultural District cut into attendance, and the community center building lacked a large warehouse space to build and store sets. In 2012, the ’Phib found and purchased its own building in the burgeoning Near Southside, not far from the Shipping and Receiving Bar. The theater’s willingness to stage unconventional shows is welcome in a city whose theater scene is otherwise mostly mainstream. Bass Performance Hall, Casa Mañana, Circle Theatre, Jubilee Theatre, Stage West, and other local theaters, with the exception of the outdoor Hip Pocket Theatre, tend to not stray too far into the alternative in what is considered a fairly conservative Cowtown. The ’Phibs’ most recent production, Northside Hollow, a about a man trapped in a mine, began in pitch darkness. Later, the stage was lit by lights attached to excavation helmets – worn by theatergoers.

“People understand what the Amphibian brand is now,” Culebro said. “We like to do things that are different and surprising. We also are committed to diverse voices. When I heard about this play written by an Iranian playwright who was held under house arrest and that his requirement was that the actor not see the script until he or she walked on stage – that, to me, was really thrilling.”