On a chilly February morning, 20 or so people were milling in an empty lot on West Magnolia Avenue. The group, consisting of Near Southside Inc. brass, members of the media, developers, and well-wishers, was waiting for the gold shovels that were piled on the ground to be put to use by men wearing suits. The groundbreaking ceremony for the 18,000-square-foot development that will house the sixth location of Salsa Limón next winter was supposed to start at 10 a.m. But 15 minutes after the scheduled start, the man of the hour, Ramiro “Milo” Ramirez, was still missing – so too was the promised food truck and its bounty of free breakfast burritos.

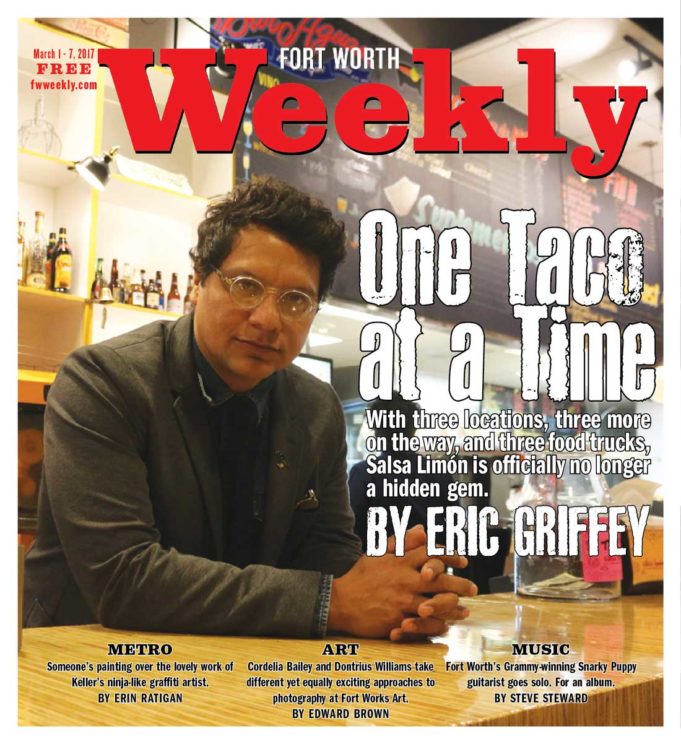

Moments before the truck pulled up, Ramirez and younger sister/business partner Rosalie “Rosie” Ramirez had arrived in a separate vehicle. In an instant, the gathering went from a pretty mundane PR event to a party. The small crowd came alive as Ramirez, animated and energetic, worked everyone with a kind charisma that sits somewhere on the hype scale between a politician pressing flesh at a rally and a celebrity author greeting fans at a book signing.

Ramirez doled out a few hugs and handshakes before wielding the shovel long enough to pose for photos with his sister, a couple of Near Southside honchos, and the developers. The gilded tools were put away after a grueling 30-second dig, then the champagne and breakfast burritos flowed.

The event was short but lively. The assembled throng slowly adjourned, and it was all over in a flash. But for Ramirez, those little ceremonial piles of dirt were more than a decade in the making.

Ramirez started Salsa Limón because he couldn’t find Mexican food that lived up to the standards of the street food he and his sister grew up eating. The Mexico City native, who also spent time in the coastal Oaxaca region, dreamed up the concept of “Salsita” – their pet name for Salsa Limón – for his final college project while at SMU.

He and Rosie opened their first store in the humble settings of an empty mall food court in 2005 and have since built up their business to be one of the most recognizable and revered restaurant mini-chains in Fort Worth. Now, more than a decade since the original restaurant opened, the “Mexican-grade Mexican” brand is growing in fast-motion. Next month, Ramirez and company will open a Salsita in Dallas, and they’ll send a food truck to Big D semi-permanently. Don’t expect the pair to slow down when that’s done.

“We want to wow the world one taco at a time,” Ramirez said. “Everywhere in the world deserves a good taco.”

Just seven years ago, Salsa Limón had one brick-and-mortar location at La Gran Plaza. In what seemed like an instant, the purveyors of authentic Mexican street food have opened three locations with three more scheduled to come online over the next year. That’s not even counting the Ramirezes’ fleet of food trucks or the spot near the Cultural District that had to close because the building was slated to be bulldozed. (Ramirez and company picked up and moved the entire building to another part of town.) Milo and Rosie, who work under the umbrella of their own creative incubator, Frankenstein LLC, also own Gorgonzilla food truck and plan to expand that company. Last year, Ramirez somehow found the time to open Downtown cocktail bar and restaurant La Perla Negra with two other prominent restaurateurs. He sold his share of the business when Salsa Limón started cloning itself throughout North Texas.

Ramirez’s story isn’t your typical immigrant-turned-entrepreneur tale. He didn’t sneak into the country illegally; he comes from an educated, successful family; he’s traveled the world; he’s earned a degree; he’s worked as a marketing executive; and his artwork has been displayed in prominent local shows. But the budding Salsa Limón empire draws from every phase of his life.

And while it may not have exactly been a rags-to-riches story, the rise of Salsa Limón hasn’t come easily or without adversity. The company survived a recession, a theft, an oft-contentious rivalry with Fuzzy’s Tacos Shop, the aforementioned building that was to be demolished, and plenty of other headaches.

Ramirez said that his restaurant has lasted because he has clung to its core principles. His philosophy is centered on producing a product that is engineered to please a Hispanic consumer base above all else.

“The notion that we didn’t put any stops to the recipes of how we produce our street food is a sword that many other restaurants fell on,” he said. “They felt like they had to tone it down.”

These days, developers all over North Texas are lining up to get Ramirez and company to open a new location in the latest shiny development. Not bad for a restaurant that existed only at “The Mexican Mall” just a few years ago.

*****

Ramirez is incapable of speaking without using his hands. He sometimes waves them so wildly you instinctively flinch to defend yourself. He often speaks in metaphors and frequently starts one thought before thinking of a more succinct way to convey the idea mid-sentence. His mind works like a Swiss-made watch – the gears are always turning. Rosie is quieter, until she’s not. The two describe their relationship as a game of tennis, alternately taking turns playing the part of the big dreamer and levelheaded realist.

It’s difficult to keep up with Ramirez, who speaks fast and refers to his business by several names, including “Salsita.” He and his sister have given each Salsa Limón location a Spanish moniker. The downtown spot is Centro, the outpost on University Drive near TCU is known as Universidad, and the original location is called simply La Gran Plaza. The soon-to-be-open locations will be in the River District (Distrito), the Mayflower building in Downtown Dallas (Flor de Mayo), and the uncharacteristically Anglo-sounding “Maggie” on Magnolia.

On a recent weeknight evening at Centro, Ramirez and Rosie waxed poetic about how far they’ve come. The pair flung around corporate jargon, referring to their business as a “brand” just as often as a passion project.

It was Ramirez’s keen business sense, his ability to grasp the bigger picture, that attracted Andrew Segal, whose Houston-based company, Boxer Property, owns La Gran Plaza.

In 2005, Segal was introduced to Ramirez through a friend in the Dallas restaurant business named Brady Wood, who now co-owns the Coyote Drive-In downtown. Ramirez pitched the concept to Wood almost a year before meeting Segal.

Segal and a business partner had just bought the nearly empty mall, then known as Town Center, and were in the middle of re-branding the space to attract the nearby Hispanic community.

“We had a bunch of people who were just starting to come to the mall, but we had nothing to feed them,” Segal said. “I knew that, not only could [Ramirez] pull this off, but he really understood the culture and the market we were going for. He had a great feeling for the project. It was our first real legitimate restaurant that we opened in the mall. It was right by the door, and it really set the tone for this 1.2 million-square-foot project.”

Segal gave a loan to Ramirez to open the original Salsa Limón. He said he’s not surprised that Salsita has grown the way it has. The restaurant, he added, isn’t some scrape-knuckle, seat-of-your-pants operation but rather a carefully crafted business governed by a master plan and unflinching principles.

“I knew something that people didn’t know: [Ramirez] gives his concepts a simple [veneer], so it looks like it’s a mom-and-pop that’s crossed over,” he said. “But when you talk to him, you’re speaking to someone who really knows the physics of what he’s doing.

“What was exceptional about him is that he embraced what we call the back of the house,” Segal continued. “He really got into systems, checklists, food safety, and processes, even when he had only one restaurant. It was exciting to see this little place that made people think it was simpler than it was but was run more like a franchise.”

Aside from the loan, Segal also gave Ramirez a car and a place to live. The loan spared Ramirez the trouble of finding investors and allowed him to own the majority of his business. The debt, Segal said, was repaid in full.

By 2010, Salsita was a hit with Hispanics. The place stayed open until 4 a.m. on Saturdays and benefited from the deluge of people that emptied out of two nearby nightclubs. Ramirez and company set up a karaoke machine to keep the party going.

Ramirez and Rosie wanted to cross over to the mainstream and bought a food truck just at the moment that trend was hitting the nation. They would occasionally set up shop outside of the Chat Room Pub on Magnolia, but the truck was mostly a staple outside of The Cellar on West Berry Street, where it stayed open after-hours and catered to drunken TCU kids.

The Berry Street locale was directly across from Fuzzy’s Taco Shop, and the two competed for a share of the same market.

“They hated us,” Ramirez recalled. “At 2 a.m., we’d have a 50-person line. It looked like a rock concert.”

“Very rough” is how he described his relationship with Fuzzy’s.

“We got a lot of mysterious visits from the health department,” Ramirez said. “We were the only two places open late. You don’t have to be a genius to figure that out.”

The Salsita brand was landing with the gringos, but the added stress was also taking a toll on Ramirez and Rosie, who felt like they were working two full-time jobs.

“Imagine being there until 3 in the morning getting your ass kicked, then you have to clean all night,” Ramirez said.

*****

The food truck introduced Salsa Limón to a new pale-skinned audience. Ramirez and Rosie bought a second truck that frequented the suddenly hot food truck parks around town. But the real breakthrough for Salsita came when Ramirez and company opened their first brick-and-mortar spot in a tiny, diner-style building on University Drive, across from the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

The owner of the building that sat on the outskirts of the West 7th corridor initially wasn’t keen on renting out the place to Salsa Limón. Ramirez said the owner didn’t want them staying open late, didn’t want them to serve alcohol, and was creating all kinds of other barriers.

“We wanted to be close to the Modern,” Ramirez said. “Our background is art. To us, to be next to that building was very enticing. But after a while we were like, ‘This guy is insane, telling us how to run our business.’ Nothing was really working.”

A friend of Ramirez who also happened to be the nephew of the property owner intervened, and the location was a hit from the get-go.

“We opened it, and immediately it was like paradise,” Ramirez said. “It was a new kind of operation for us. Year one blew away our expectations. Year two tripled our expectations. By year three, we were doing numbers that blew away the landlord and the developers.

“We were finally at a point where we weren’t worried about making payroll,” he added.

The two caught their breath just in time to open a second storefront, this time returning to University Drive to reconnect with a new generation of TCU students and rekindle a rivalry with Fuzzy’s.

Just when everything seemed to be going right for Salsa Limón, Ramirez got the news that the property owner of the Museo location would be tearing down the historic building.

“You should have seen my face when they told me, ‘We’re going to tear this building down,’ ” he said. “I was very disturbed.”

It was around that time when another developer started recruiting Ramirez to open a place along White Settlement Road and the Trinity River in the 276-acre River District development.

In July, the city’s Historic and Cultural Landmarks Commission voted to move the historic art deco-style building to the River District. The move was a huge PR win for Salsa Limón. Television camera crews and numerous print media outlets showed up to watch as a crew picked up the entire building and loaded it on a truck.

Amid that chaos, Ramirez and Rosie seized an opportunity to jump into a lease downtown, and for the first time opened a place with a full bar. The two also signed a deal to open a location in Dallas – running counter to the trend of Dallas chains setting up shop on this side of I-30.

Ramirez used a World War II analogy to discuss his strategy of having both the brick-and-mortar location and the food truck in the city to the east.

“It’s going to be a kamikaze,” he said. “It’s like the invasion of Normandy,” he corrected himself. “We’re coming in by sea, and we’ll have air support. We’re going to establish a beachhead.”

The Dallas Mexican food scene, he said, doesn’t intimidate him.

“There are a lot of Dallas tacos that are really not that great,” he said. “We’ll lap them. And there are a few other [good restaurants] that we can share the patronage with.”

The two have already made a few trips to Dallas in their food truck, and Rosie said people instantly connect with the food.

“It’s something that’s so traditional in Mexico, and it has been welcomed by everyone,” she said. “When we had the truck, we would see people come up, buy a taco, go and sit, take a bite, and wait for the ‘yes’ moment.”

Ramirez and Rosie have never lacked for ambition or vision. Ramirez talks of roaming llamas and hosting light saber battles in the backyard of Distrito. He imagines customers visiting Maggie and strolling down Magnolia with a spiked agua fresca to Melt Ice cream to end their night.

*****

As a child, Ramirez split his time between Mexico City and the west coast of the Oaxacan region. His mother, a doctor, grew up speaking Zapotec, the tongue of an ancient culture that dates back to the Mayans. His father was a first generation Mexican-American born in San Antonio.

Ramirez’s time in the rural coastal area of Mexico was formative. Every day, fishermen sold fresh seafood at the market, and the landscape was dotted with mango plantations and other farms. He developed a love for diverse food and an impossibly high bar for quality.

He came to the United States for high school at Culver Military Academy in Indiana. He was the youngest and smallest kid in his class at an American military boarding school, an experience he said made him a more empathetic and caring person.

After finishing high school, he moved to an Israeli kibbutz on the Gaza strip. There, he met people from all around the world and learned how to work in a cooperative. After about six months, he bummed around Europe, often sleeping on the roofs of youth hostiles at a discounted rate.

Some friends of his lived in Dallas, and they lured him to the city to attend SMU. He earned a degree in business administration with a focus on entrepreneurship, and his final assignment was to write a business plan.

“Every time I would go get tacos back then, I would say, ‘I know I can do better than this,’ ” he said. “I would get so frustrated with tacos. The salsa was all watery, and there was no spice. I would walk out fuming from Mexican restaurants, like, ‘Why is the salsa not spicy?’ ”

The design for Salsa Limón was an amalgam of three places from Ramirez’s youth. One was a Mexico City taco joint that served only meat from the cow’s head.

After college, Ramirez took a job crunching numbers at Eatzi’s in Dallas, the predecessor to Central Market. There, he got a front-row seat to see how systems were used to run a company.

He left that job to work for a creative firm in Dallas and eventually started his own company that plastered ads on trucks. When the economy crashed in the early aughts, the project went belly-up. He went to work for a friend as a copywriter, and one of his clients was McDonald’s, which hired him to reach out to the Hispanic community.

While working on that project, he was struck that even Hispanic marketers were marginalizing Hispanic consumers. He understood that Mexican actors would appeal more to a Hispanic population.

“In the Mexican way of advertising, every one of the actors were white,” he said. “Everyone in the commercials had blonde hair and blue eyes. My philosophy was to always show the consumer consuming.”

It was during his time working with McDonald’s that the fire for Salsa Limón rekindled. Hispanic focus groups all over the country were frustrated by the chain’s lack of flavor and spice.

“I started getting more and more encouraged about revising the concept of Salsa Limón after hearing the consumers asking for something I had thought about since college,” he said. “When I wrote Salsita in college, it was meant to target the whole country. As I examined Hispanic society, I said, ‘I’m going to write this for the Hispanic market now.’ I rewrote it. I showed it to a couple of people I knew in Dallas who could pull it off.”

One of the people he met was Brady Wood, who would introduce him to Segal months later. In the interim, he landed a cushy gig as lead creative for Chevrolet in Miami. When Segal told him he’d front him the money to start Salsa Limón, it wasn’t an easy choice.

Ultimately, he couldn’t pass up his longtime dream or the opportunity to bring authentic, elevated Mexican cuisine to the masses.

“Right now, our habanero is a criminal,” he said while eating at Centro. “It will make your snot flow like the Mississippi. But that’s how it is. We don’t have control over the chile. If it comes to us spicy, it goes out to the consumer spicy.”

Salsita’s recent spate of success has justified a lot of the tough decisions and hard time Milo and Rosie have experienced over the last 10-plus years.

“This is what happens when all of the opportunities line up,” Ramirez said. “All of a sudden you’re sitting there, and all of the lights are green. And all you have to have is the follow-through to go forward. It gets difficult and scary, but if you go through it, it pays off handsomely.” l

I do wish you would do an investigation of the slumlords (B&G Rentals, office located on Hemphill Street in Fort Worth). See TAD.org for the number of houses in Fort Worth owned by the Soan Trust (Hollis Glenn and Barbara Sloan, both now deceased) and all except one rented out -operated by their daughter Shane Sloan Wolfe and her son as B & G, as it was before by Shane’s father exactly the same way. They rent to Sec 8 voucher people, but refuse to allow inspectors inside their houses – renters are told they will immediately be evicted if they let ANYONE inside. Bad, bad things happen at their houses – they are unsafe and not secure. Contact Becca Krecek; she has a website (private and secret for fear of retaliation from B & G) on Facebook and there will be a meeting today of lots of Fairmount people who have lived with these houses and their resident drug dealers, bloody attacks on residents in front of young children, and other terrible things. B & G fails to vet people they rent to except for quickly checking the on-line sex offender website to determine how far they are from schools – then it is believed they bribe people in all directions. Thanks, Mary L. Branson, 817 922-9537, 1420 S. Adams St, 76104. I live across the street from one of their many houses, zoned multi-family, but operates as a rooming house. Their taxes and house evaluations do NOT ever increase either; they appeal and win (stable of REALLY good lawyers).