It’s 9:30 at night, and my boss and I are trying to start a camp fire in three feet of snow. Rumor at the saloon was that something had been stalking and abducting people in the woods, but right now, all we want is a little comfort and maybe some cocoa. We’re ready to break out the lighter fluid when three figures emerge from the shadows and, within seconds, beat us bloody with weapons and psionic fire. We are bound and dragged into the woods.

Over the next 10 minutes, the attackers tie us to a tree and torture us — not for information, just for sick pleasure. I grab my boss’ hand and shit-talk our torturers with all the spite I can muster, trying to distract us both from the pain.

Blinded, burned, and beaten, we eventually are left to call for help, a trap to lure more torture victims. None come. Finally, the monsters drag us off again, break our legs, and abandon us to the hollow groan of an approaching horde of shambling zombies.

We’re doomed and miserable — but, hey, everybody needs a hobby.

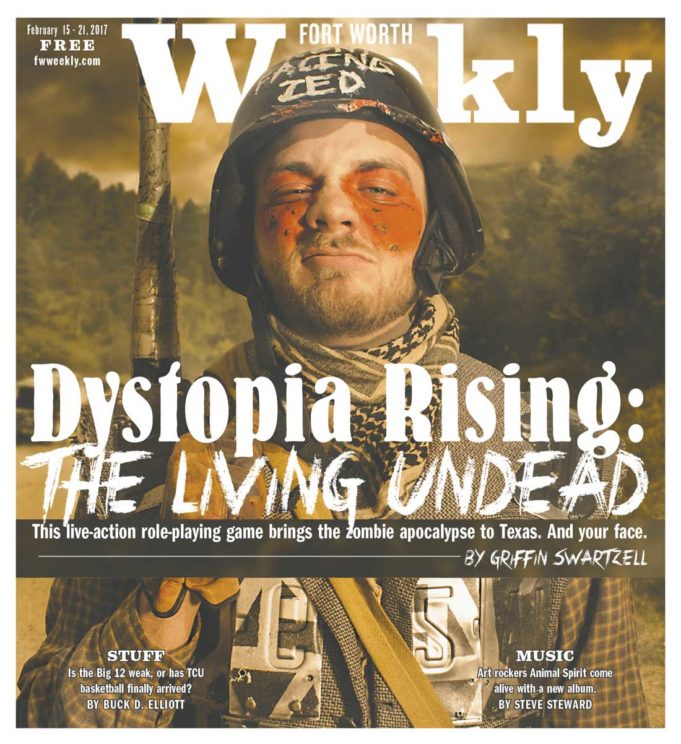

If the zombies and pyrokinetic torture-cultists didn’t give it away, this was a game. I was at Beaver Ranch, a wooded community park in Conifer, Colo., half an hour southwest of Denver. Around 150 people from around the country had rolled up in their post-apocalyptic finest: thrashed-out trenchcoats, chainmail made from soda can tabs, and at least one foam sword inscribed with “LIMBS ARE A PRIVILEGE.” We were there to do battle with hordes of undead and other nasties in the fictional Colorado outpost town of DedStop. We were there to play a game of survival, adventure, and horror called Dystopia Rising.

Dystopia Rising, or DR, is a live-action role-playing (LARP) game that takes place at campsites in 16 states, including Texas, with more chapters set to open this year. It’s all one game. The estimated 6,000 active players in third-quarter 2016 regularly traveled from state to state, growing their characters, trading resources, and building ties that can be carried to any site.

Dystopia Rising launched in 2009, but the oldest parts of the game date back to 2001. Co-owner/co-founder Michael Pucci was writing it as a then-unnamed pet project between day jobs. It coalesced into its current form in 2008. Inspiration struck while he was at Gathering of the Vibes, a Connecticut music festival, when a heavy storm tore through, trashing the tent city. The morning after the storm, according to a five-year anniversary article written by DR social media manager Catherine Griffin, a man came through to sell popcorn and hot dogs to the huddled masses for five bucks each.

“It became concrete in my mind right then,” Pucci said in the article. “No matter what happens in the world, we will always have people trying to better themselves at the expense of others while clusters of others would latch together. That sort of human nature, and the way people clung to one another, was the basis of what would later be my envisioning of post-apocalypse culture.”

That vision presents a world generations after nuclear warfare and zombies have wiped out civilization. During that fall of humanity, some people had chance genetic immunity to the zombie virus, and, though infected, they didn’t turn into mindless undead. The survivors adapted, not just culturally but biologically, diverging into different varieties of sorta-humans called Strains, who range from rowdy redneck Mericans to visibly decayed Retrogrades to blunt, angry Yorkers.

Survivors try to form functional societies while fighting off zombies, rabid humans called raiders, religious fanatics, mutated animals, disease, and, as often as not, one another.

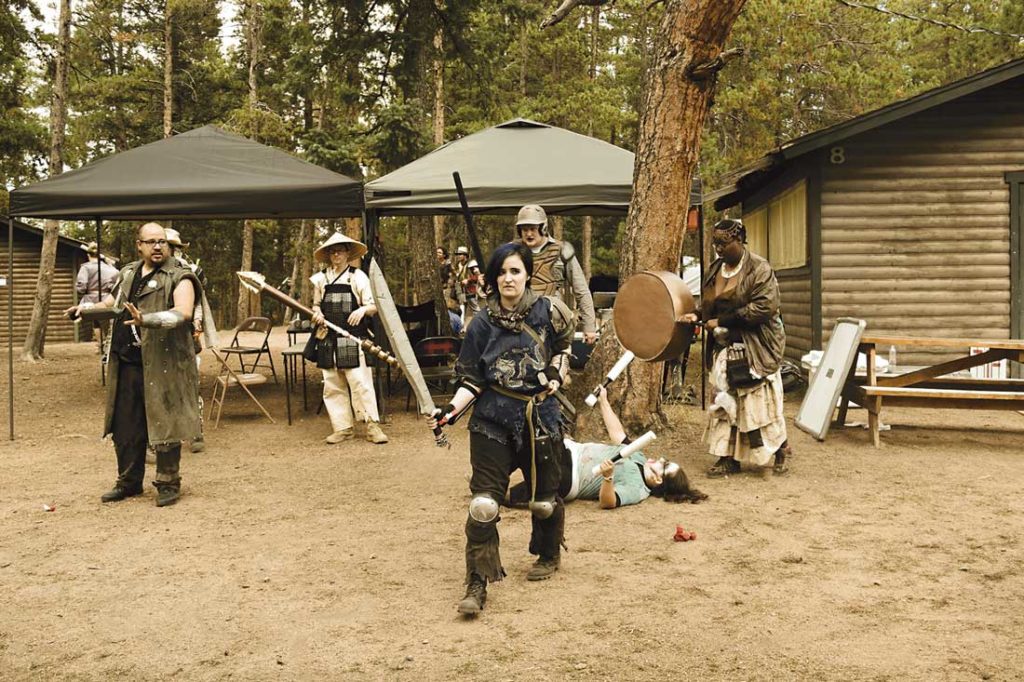

Some take up arms — actually Nerf guns and foam weapons called boffers. Others become artisans and experts, from brewers and builders to doctors and draftsmen. Many take up faith, cargo-cult religions that have formed around everything from radiation-induced mutation to pre-apocalypse TV and music broadcasts.

When Pucci and his partner, co-owner/co-founder Ashley Zdeb, launched the game, it proved “really fortunate timing for us, since Fallout 3 came out in October 2008, Borderlands in 2009, and The Walking Dead was 2009/2010,” he told us. “Having the material existing, running, and supported before the apocalypse and zombie explosion happened across all media really helped us bring LARP to non-LARPers.”

Dystopia Rising didn’t come to Colorado until 2014, when Juliet Meyer heard about it from a friend. At the time, the logistics director for the game’s Colorado branch had been LARPing for around 14 years, having picked up a game called Vampire: The Masquerade in college. Excited, she introduced the concept to now-Director of Storytelling Raymond Bruels III, a 23-year LARP vet, himself a former member of the Mind’s Eye Society LARP national storytelling staff. Both fell in love with the world and its systems.

“I have always been a fan of post-apocalyptic settings and [am] a lifelong lover of the horror genre,” he said. “Dystopia Rising gave me both. The idea of pitting players … against the elements in a struggle for survival with a backdrop of fending off a host of zombies and crazed raiders sounded just too good to be true.”

Over the course of a year, the two co-created DedStop, working with the national branch to develop specifics and make it click with the established world. They drew inspiration from existing media — HBO’s Deadwood and AMC’s Hell on Wheels, among others — as well as the Centennial State’s past.

Each of the 6,000 players spends weekends portraying a character of his or her own design, weaving a massive story that could not have been planned or predicted. They all have their own triumphs and tragedies, unique war stories, and the scars to prove it.

I spent several weekends in 2016 playing a character named Lucas, a hardboiled bodyguard and a perpetually anxious psion — he has a few reality-warping tricks, like those cultists.

*****

Though the monsters and drama in Dystopia Rising are simulated, the adrenaline is very real, the play intense. That April night in the snow, when the cultists had left my character and his boss out to be eaten, Lucas blossomed into a full character. He had to save his boss, and that meant getting the Shamblers away. When he was screaming, it was pure, organic improvisation, and it felt pretty real.

In the DR community, there’s a word for those moments when the barrier between player and character gets hazy, when a character’s feelings affect the player or vice versa. It’s called bleed, and it’s something that has to be managed. Everyone processes it differently and has different limits. Add to that the fact that DR exists as a horror game at its core, and it becomes all the more important for players to know when to cool down and to communicate when something crosses a line.

More, it’s important to distinguish between player feelings and character feelings. Players usually refer to their characters in the third person. Reaffirming out-of-game friendships after in-game conflict also helps. I like playing a non-player character (NPC) for the last few hours of each game. Getting made up as a monster and groaning for the flesh of the living can be relaxing as well as fun. (Who knew?)

Dystopia Rising emphasizes that it’s a community with a game — not a game with a community. Every player shares responsibility for making the game work. Beyond taking a shift as an NPC, some players become Marshals, volunteer staffers somewhat akin to referees.

For most, the sense of community is a big part of the draw. Bruels said his favorite aspect of LARP has changed over the years, but where he is now he “truly [enjoys] the community-building and shared storytelling experience, not only among staff members driving the plot but also the players with their own intricate backstories.”

Meyer said, “Community, locally and nationally, is important to me and has genuinely impacted my life for the better. LARPing means I have friends across the country who I share something unique with. You’re all watching the same TV show or sport in a way, and just like when you root for a favorite character or team, everyone is excited to share their thoughts and experiences.”

That attitude runs deep. When real-life problems happen, the community rallies to help.

Last summer, the house where four Springs-area DR players lived caught fire. Firefighters knocked down the blaze quickly, but the damage was extensive. They lost almost everything, including two cars.

The community immediately responded. Within an hour, three more local players were onsite to help out with transportation and moral support. And a couple hours after that, a GoFundMe.com page was up and circulating around the Dystopia Rising: Colorado Facebook group. In under a day, the community raised $1,680. A Boulder-based player even loaned the group a spare car. Since, they’ve moved into an apartment and have, as much as possible, returned to normal life.

“I am typing this with tears in my eyes because when I stood in my street watching the place we called home go up in flames, I was so unsure of what would happen when I turned to my community for help,” wrote Benji Dezaval, Char’s player, on the GoFundMe page. “I am blown away by all the help we’ve received. I can’t thank everyone enough for their donations, for the shares, for everything that you guys have all done to help us.”

According to DR co-owner/co-founder Pucci, he in part designed the game to build these ties. It’s one of the things he believes sets the game apart in the LARP world.

“Everything in DR comes back to mechanical systems that require players to engage one another to be successful,” he said. “Our biggest difference isn’t in the game but instead is our approach to community. When we first brought out our design of inclusive play to the public, our stance on equality in gender choice, and our progressive social focus to the world, we made a very public and definite stance on the culture we were looking to build. By defining the type of culture you want in-house, you are also defining what kind of culture you don’t want in your house.”

Pucci’s companies use a broad definition of harassment to describe what players are not allowed to do at DR and other events. It goes beyond the expected bans on assault, stalking, and intimidation. The community rejects all racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia. There’s also a blanket ban on so much as mentioning rape and sexual assault. Players have been asked to leave games for even joking about it.

In many nerdy spaces, harassment and hate speech remain pervasive. Companies like Microsoft still struggle to curb these behaviors in game communities — voice chat especially can be a dumpster fire for anyone who sounds feminine or non-white. But DR’s community was built by and for people who recognize the fundamentals of treating others with respect.

These standards aren’t just heartening. They’re necessary, especially for managing bleed. The game hits a wide variety of stressors over the course of a weekend. Difficult, often gray-at-best moral choices, and intense subject matter like slavery and torture come up frequently. Separating those from real issues keeps the game fun. While there’s plenty of in-game drug use and addiction, only caffeine’s allowed onsite. And instead of avoiding the subject of bigotry, DR uses bigotry against in-game religions and “Strainist” prejudices as part of the setting. The rulebook even has pages of Strainist slurs to inspire players. In DR, bigotry only hurts characters, not players.

All defined, none of these restrictions feel forced or even prominent. Players still find plenty of creative ways to have their characters say horrible, repugnant things. Out-of-game, players are too busy bonding over simulated trauma or real-world commonalities.

*****

Speaking as a lifelong nerd, I used to think of LARPing as a hobby for people with more time, money, and desire to commit to escapism than me. I had no idea how people got into it. It felt pretty far down the rabbit hole, but I was open to trying it if it came my way.

“The hardest part about LARPing is your first game,” Meyer said. “Everything after that is easy.”

Outside of the apocalypse, Meyer works in IT and creative services in the health care industry. She co-runs the Colorado chapter with Bruels, operations manager for a numismatic company when he’s not co-running a haunted attractions-centric mask and props shop.

“Your first game, there’s the nervousness of what to expect,” he said. “Are you dressed right? Is your character sheet well built? What if you don’t know anyone? Or ‘What if I don’t know a rule?’ Costumes can be bought at Goodwill stores or on Amazon, character sheets can be revised, rules can be reviewed, and your new friends are waiting to meet you.”

Players’ ages range from as young as 15 (with parental consent) to folks in their 50s and 60s. But Meyer described the typical DR player as “in their late 20s to early 30s, sociable, [and] employed.”

Participants, Bruels said, come “from all walks of life. I’ve met doctors, lawyers, tradesmen, college students, business professionals — LARP does not discriminate and is an open hobby to anyone with an interest or passion.”

Meyer said LARPing isn’t about “who you are in your day-to-day. It’s about stepping away from yourself and taking a mental vacation for a few days or a few hours.”

In my case, a few friends, new to DR themselves, asked me to come along with them last March to check out a single afternoon preseason event. It was affordable and outdoors, and I sorely needed exercise. Plus, I rightly assumed it would be easier to pretend a dead, brown March day was post-apocalypse Colorado than, say, a faux-English fantasy fiefdom. So I spent an afternoon skimming the free rulebook, wrote up a tough-guy bodyguard, and built a costume from ratty clothes in my closet.

Over the course of the season, “Lucas” grew from a walking anger problem dressed like off-brand Kurt Cobain into someone three-dimensional, lived-in. As I learned more about the world, it got easier to get immersed. And with a lot of help, I built a more complex costume, too. The resulting pride from making something cool and developing a satisfying character arc is its own reward — you get out what you put in.

Still, the sheer scale and openness that makes the game exciting does tend to build up a perceived barrier to entry for first-timers. Everyone who LARPs has to overcome it — even co-owner/co-founder Pucci.

“My first exposure to LARP was in 1994 with a Vampire game,” he said. “At first, I didn’t really dig it because the people involved in the game were really caught up in their own things, and it sort of felt like I was visiting someone else’s family reunion. Sure, it seemed like people were enjoying themselves, but I wasn’t sure how. I went back to the game a few times and joined a couple friends to try a boffer LARP called Pandemonium.

“It wasn’t until a LARP in Scotland when I was visiting my brother that the hobby bit me. The game took place at a pub, there were scenesters all playing the game and having drinks, and they asked me to NPC a vamp hunter.”

He started running his first LARP in 1996, taking only a few breaks since. Now 38, he makes his living mostly with LARPing, but that’s a pretty recent shift. When Dystopia Rising first debuted in 2009, Pucci and co-owner/co-founder Zdeb were both employed more than full-time.

“I was working about 70 hours a week on the road as a field manager overseeing licensed businesses and was expected to be on call for these businesses another 20-plus hours a week,” Pucci said. Zdeb “was doing 70-plus hours working for a company that really did not treat its employees like humans. The entire time we were doing this we were running a game that was regularly 40 or so people out of my house or a park. Supporting this game to the level we wanted to was like having another part-time job, and really we were reaching a point where we needed to change how the overall work and life equation was working. … I finally looked at [Zdeb] and said, ‘I want to run LARPs for a living.’ She said, ‘Well, do it then.’ ”

Going fully professional was a big learning experience for the couple. But as with anything worth doing, they persevered and have built their game into a collection of small companies that keep them and others afloat. Eschaton Media is the publication arm, producing print and digital materials, like the rulebook. Dystopia Rising LLC handles the franchise network, producing materials and supporting the franchised chapters. And Imagine Nation Collective produces Dystopia’s bigger live events, including an upcoming collaborative event for which they’ve rented the entirety of the battleship USS New Jersey.

*****

Lucas’ story is one of hundreds that ran through DedStop alone in the 2016 game year. All of the characters he crossed paths with have rich, complex lives all their own. And every player behind those characters has his or her own reasons for coming to the game.

For me, as much as I dig fighting off zombie hordes, I enjoy exploring Lucas’ turmoil for its own sake. Dealing with his experiences also helps me practice parsing my own stresses and anxieties. I’m not the only one who gets real-world benefits from this game.

“The leadership and public speaking skills learned in these games translate directly to my personal and professional life,” Colorado’s Meyer said. “In LARP, you learn a great deal about people, leadership, and how to deal with failure, or success, gracefully. It’s a wonderful social sandbox that’s a safe place to learn about yourself and what you’re capable of.”

Co-owner/co-founder Pucci said his LARP hobby is “fun, it’s dramatic, it builds friendships, and it can even be physically exhilarating. LARP is filled with some of the most amazing people I have met in my life from around the globe and has provided me some of the best excuses for experiences ever.”

But he doesn’t try to convince people to do it.

“I just show them how cool the things I am doing are, maybe play one of the videos to share it, and if they want to come out to try it then, I help facilitate it,” he said. “If they aren’t interested, we get another round at the bar and rack the tables again.”

Storytelling director Bruels recommends reaching out to the community. The Facebook groups for the game overall and for the Texas branch are both active. Community members will readily provide answers and advice. The digital edition of the rulebook is free online, too. Hell, shoot me an email at gswartzell@csindy.com.

Dystopia Rising first landed in Texas in October 2012, thanks to Ryan Coogan and wife/partner Sara Hart, who both played “in the New Jersey branch when it was, literally, the only Dystopia Rising game.”

The couple eventually relocated to Texas for Coogan to attend Texas A&M. “We didn’t want to not have this thing in our lives,” he said.

The 2017 schedule for the Texas game can be viewed at Dystopiarisingtx.com. Events run monthly until May. The next gathering is Friday, Mar. 10, at 10 p.m. and goes through Sunday, Mar. 12, at Camp Kachina, 14750 Camp Kachina Rd., in Belton, about two hours south of Forth Worth. A player’s first game costs only $20.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Colorado Springs Independent.