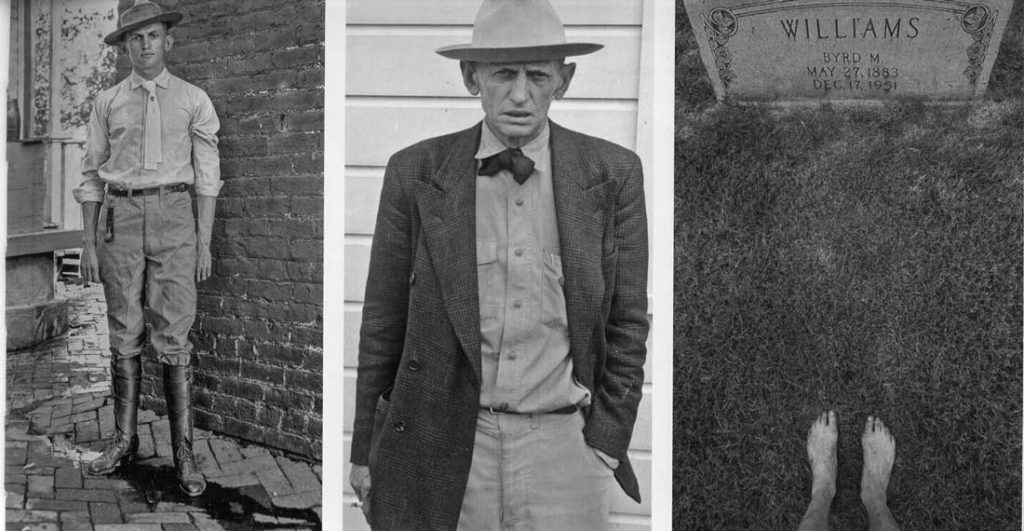

Byrd Williams Sr. could not have known what he was starting when he bought a simple Kodak camera in the 1880s. The dry goods merchant in Gainesville took photos of friends and relatives, nothing too artistic or innovative, just some decent amateur photography. He sold cameras to customers. He created and sold postcards featuring his own images. And over the years, he turned his hobby into a passion so deep that it would spread to three more generations of offspring, each one becoming more ardent than the previous. Byrd’s son, grandson, and great-grandson – Byrd II, III, and IV – would collectively create tens of thousands of printed photographs and hundreds of thousands of negatives depicting 120 years of American life, mostly in North Texas.

Several years ago, Fort Worth Weekly became the first publication to spotlight the huge collection in a photo essay (“Byrds’-Eye View,” Aug. 12, 2009).

All the Byrds come across as charming and quirky, yet earnest, documenters of their times in Proof: Photographs From Four Generations of a Texas Family, a monograph published by University of North Texas Press in late 2016 to serve as an archival digest of the collection. UNT took possession of more than 10,000 prints and 300,000 negatives, along with letters and cameras, in 2014.

Byrd II settled in Fort Worth in the 1920s, worked as an engineer, and carried a camera along on his many travels to building sites across the West. Like his father, he was an amateur shooter, but his camera became a regular appendage in his work and social life. His son, Byrd III, would carry the legacy further, becoming the family’s first professional commercial photographer, with a studio in Fort Worth. Byrd IV also turned pro and made Fort Worth one of his primary subjects, combining artistic, conceptual, and documentary styles of photography into his work to capture the city’s visual flavor.

The 193 mostly black-and-white photographs depicted in Proof are remarkable, despite some grayness and lack of contrast in a few prints, particularly those shot by Byrd III. But magic is everywhere in this collection. Byrd IV’s pictures are the most technically right, in part because he relied on more modern equipment.

He seems to have the best eye for composition as well. His triptych featuring his twin sister is breathtaking. Pam is shown as a young girl saluting playfully to the camera in 1957, then as a pretty young woman wearing heart-shaped sunglasses and earrings with red lipstick, and, finally, lying on a couch, older, just deceased, dead from cancer, her eyes closed and face gaunt but still reflecting shades of her earlier beauty and youth.

The book’s text, written by Byrd IV, is a welcome surprise. He describes his thoughts in the same mercurial, idiosyncratic way he points a camera lens at the world. He is an engaging intellectual rooted with a Texan’s down-home sensibility and turn of phrase. Here he describes his decision to become a photographer: “It was never about the money; I could have done better mowing lawns. There was always this urgency about it: save all historic buildings, remember all the faces, stand on all the street corners, save everybody’s toilet, share my experience with posterity, I was alive goddammit.”

Photography for him was an attempt to “put memories into sticks and stones,” and years spent in darkrooms inspired much “self-introspection while treading in an odious chemical bouquet.”

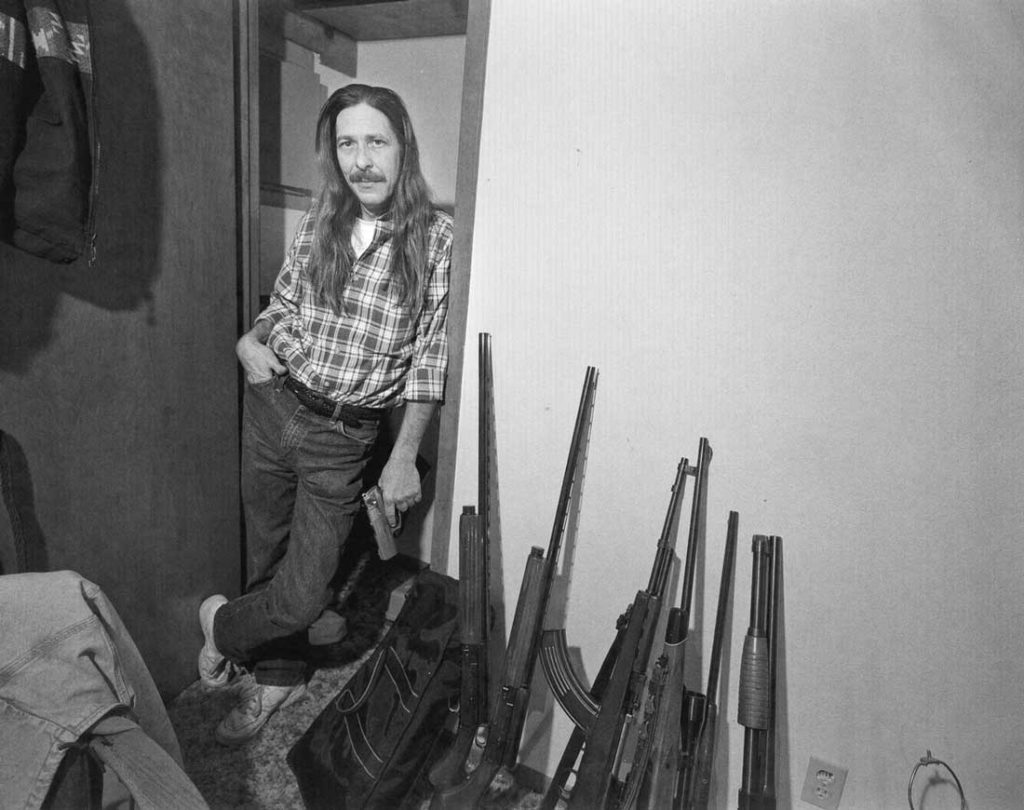

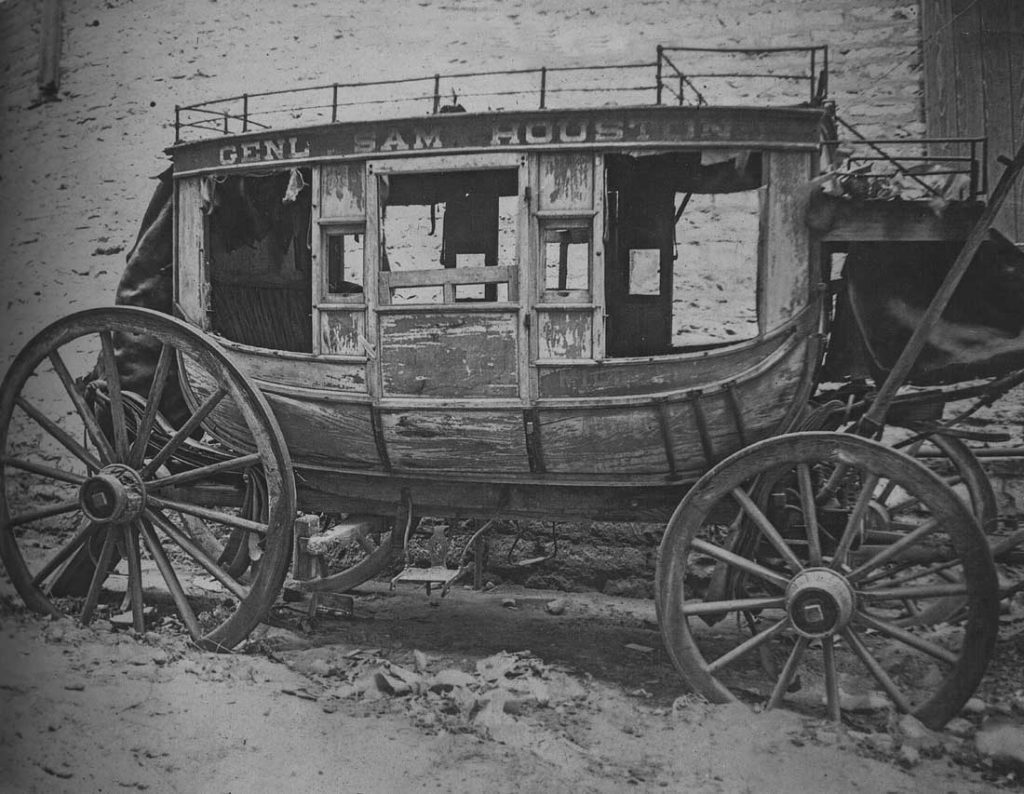

Despite Byrd IV’s vivid rhetoric, it’s the photographs that remain front and center. The images are organized by themes, such as “Landscapes,” “People,” “Night,” and “Violence and Religion in Texas.” Even someone who doesn’t read a word of the text will enjoy flipping through this more than a century of Americana. Each page opens a new world: donkeys loaded down with water bottles in El Paso circa 1907; a man’s admiring glance as a woman walks by on a Fort Worth street in 1937; a woman feeding nickels into an old Wurlitzer jukebox in 1947; a boy sitting in a toy car at Monnigs Department Store in 1953; a hairy muscleman in 1954; two boys playing cowboy in 1960; an old man sitting at a domino table in 1981; the front of the Alamo shot by three different Byrds, in 1890, 1947, and 1970; a drug dealer (or “addictive substance vendor” as Byrd IV calls him) holding a pistol and standing beside a row of rifles leaning against a wall in 1989; a men’s washroom attendant sitting beside his table of toiletries near a long line of urinals at Billy Bob’s Texas in 1996.

For many years, Byrd IV has hauled around four generations’ worth of photos and negatives, hundreds of boxes, dusty, heavy, vulnerable to light and temperature, filled to capacity and toted to various living rooms, closets, garages, and attics.

“I had to get it somewhere safe,” Byrd IV told me this week on the phone. “It needed to be in an institution … to preserve it.”

Neither of Byrd IV’s sons has taken up photography as a hobby or profession, and he was afraid the collection might degrade and be tossed after his death.

Proof puts the highlights of that anthology directly into readers’ hands in clean, glossy, black and white goodness.

Proof, by Byrd M. Williams IV. UNT Press $39.95 213 pps.