Amid this current efflorescence of African-American cinema that we are lucky enough to be living through, there has been a curious void. Where is the great gay romance among these movies? Where has been the black equivalent of Brokeback Mountain or Carol?

Well, that film is called Moonlight, and it’s on the same level as those others, though it bears a closer resemblance to Wong Kar-Wai’s 2001 romance In the Mood for Love, a love story of regrets and missed connections. It’s one of the best things you’ll see all year, and it’s coming soon to theaters in Arlington and Grapevine.

Based on Tarell Alvin McCraney’s unproduced and better-titled play In Moonlight, Black Boys Look Blue, the movie is neatly divided into three sections, each labeled with the name that the main character goes by. In the first, he’s Little (Alex Hibbert), a Miami boy who cloaks himself in sullen silences to escape the bullying he gets from other boys, as well as his home life presided over by a crack-addicted mother (Naomie Harris). He gets taken in by Juan (Mahershala Ali), a kind man despite his profession as a drug dealer, who seems to instinctively know how to parent this kid. In the second, he’s a high-school student known by his given name of Chiron (Ashton Sanders) — that name rhyming with “Tyrone” — who falls for a smoothly handsome classmate named Kevin (Jharrel Jerome), only for two acts of violence to drive them apart. In the third, he’s Black (Trevante Rhodes), an Atlanta drug dealer who returns home after getting phone calls from his mom and Kevin (André Holland), both of them full of remorse over what they did to him.

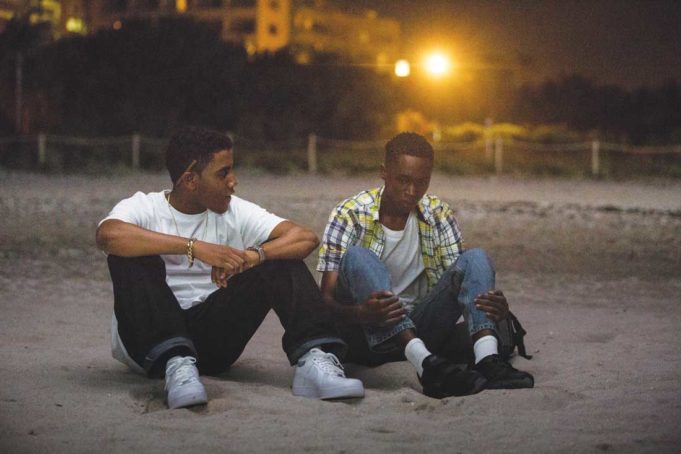

This is the second film directed by Barry Jenkins, whose one previous movie (called Medicine for Melancholy) I haven’t seen. He seems to have sprung into the world fully formed, so complete is his control over what goes on here. He directs mostly in an unfussy, realistic style, but he can do flamboyance when he feels the need, as in an expansive circular tracking shot early on around Juan and one of his dealers, and a rhyming shot later around a schoolyard brawl. His movie is full of such structuring callbacks, like shots of Chiron/Black soaking his face in a sink filled with ice water, or the use of a delicate Aretha Franklin song, “One Step Ahead.” His handle on atmosphere is such that he makes the sand and waves of south Florida feel like an integral part of his characters. I don’t know if the conversational exchange between Chiron and Kevin on the beach was part of McCraney’s play or was added by Jenkins to the script, but it’s an exquisite piece of writing regardless. Talking about the ocean breezes, Kevin says, “Sometimes one of them comes through the ‘hood, and the whole world seems to stop. Makes you want to cry.”

All this formal excellence is complemented by terrific performances up and down this cast: Rhodes, letting loneliness seep through Black’s armor of muscle mass and gangsta trappings; Holland, delivering a monologue about how much more rewarding it is to live without crime; Harris, whose strung-out appearance contrasts starkly with her plush role in the James Bond movies; Ali, embodying all the contradictions of his complex character; and Janelle Monáe being softly maternal as Juan’s girlfriend, who continues taking care of Chiron after Juan dies. The younger actors distinguish themselves, too, as Sanders copes with his mom’s worsening addiction while continuing to be harassed at school.

Most of the celebrated black movies recently have been about historical subjects and big issues: racism, slavery, the civil-rights movement. These things should be addressed by movies, but surely the search for love in this world is as important. For a variety of reasons fair and unfair, African-American films generally haven’t been taken seriously when they’ve taken romance as their main subject. It probably shouldn’t have taken us this long to acclaim one as a great film. However, only a stone-hearted homophobe could fail to be moved by the great, aching, indelible romantic moment late in the film when Black stops in at the diner where Kevin works, and Kevin serenades him with “Hello Stranger” on the restaurant’s jukebox while the two men stare at each other and ponder everything that’s passed between them. The scene seems to sum up Moonlight’s intoxicating power.

Moonlight

Starring Trevante Rhodes, Ashton Sanders, and Alex Hibbert. Written and directed by Barry Jenkins. Rated R. Now playing in Dallas. Opens November 18 in Tarrant County.