Pen in hand, Tucker Dean stopped to sign his name.

“I want to help out any way I can,” said the UTA drama major. “I just disagree with it in general.”

The “it” he doesn’t like is the Dakota Access pipeline, proposed to transport about half a million barrels of crude oil daily across four states and more than 1,000 miles.

Dean was one of about 50 people, students and non-students, who had stopped by UTA’s University Center Mall during a pipeline protest. To show support for the Standing Rock Sioux, a 16,000-member North Dakota tribe affected by the pipeline, all 12 active members of UTA’s Native American Student Association arrived [at different times] to help collect signatures to add to a petition. The 22-year-old campus organization is out to amass 500,000 names as soon as possible to send to key decision makers, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the 241-year-old department that provides public and military engineering services to lessen the risk of disasters.

The association’s petition has about 175,000 signatures so far, according to Sampson Dewey, a sophomore mechanical engineering major at UTA and vice-president of the association.

Standing Rock Sioux, believing the pipeline could jeopardize their water source, have garnered national attention over the past several months, since construction on the pipeline began. The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and USA Today have been covering the movement closely.

Along with everyone else worried about the pipeline, members of the association refer to themselves not as “protestors” but “water protectors.”

“It’s not just a Native issue,” said Kristy Willis, a junior communications major at UTA and president of the association. “It’s vital for us to come together no matter what race, color, or religion you are. We are ultimately still looking for a way to stop the whole thing.”

The water protector movement also has a spiritual aspect. Some Native Americans believe past prophecies are coming to reality.

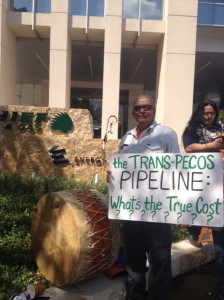

One involves a “black snake,” said Roberto Lujan, who also has been involved in ongoing efforts to fend off a pipeline near his home in the Big Bend area.

“When that goes across the land,” he continued, “it is bad.”

The “black snake” begins in North Texas. Dallas, specifically. That’s the location of Energy Transfer Partners. The 21-year-old company cofounded by Kelcy Warren with Ray Davis which is responsible for the pipeline was the sight of another pipeline protest. Led by the American Indian Movement of Central Texas, a group whose members work to protect and preserve the American Indian way of life, the water protectors in front of ETP’s Dallas headquarters recently numbered around 200 and, in addition to Willis and Dewey, included actors Arthur Redcloud (The Revenant) and A. Martinez from the TV series Longmire. The water protectors, some dressed in full traditional American Indian clothing, carried signs, chatted with one another, and shook hands with supporters.

Around midday, several of the men had encircled a drum on the sidewalk and beat out sacred songs as business people gazed from their office windows above. Police officers had stood by casually as native children toddled in the grassy areas along the sidewalk. It was a peaceful gathering.

But by morning, the earth had shaken.

Willis, a member of the Choctaw Nation, had camped that night in Oklahoma, she said, and around 7 a.m., the largest earthquake in that state’s recorded history struck.

“I thought it was a dream,” she said.

The 5.8 quake originated in North Central Oklahoma but reverberated all the way to North Texas and beyond. Technically, no one, including the United States Geological Survey, can determine what caused the tremors. Less technically, Oklahoma officials quickly closed a number of nearby wastewater wells. These reserves of briny water are used by natural gas developers during fracking, a method of releasing natural gas from shale rock deep underground and a highly possible cause of all of this region’s recent seismic activity.

Yolanda Bluehorse, a representative of the American Indian Movement in North Texas who helped organize the pipeline protest in Dallas, said that while she does not speak for all Native Americans, because each tribe has its own beliefs and spiritual interpretations, she believes, “Mother Earth is trying to tell us something.”

Willis said she wonders what might happen if a big earthquake were to happen along the route of the Dakota Access pipeline.

“Everyone needs drinking water,” she said, “not only this generation but generations to come.”

*****

The pipeline is proposed to travel under the Missouri River, and that’s what has the Standing Rock Sioux so concerned. The Missouri is their chief source of water.

In a September 13 memo to Energy Transfer Partner’s 10,000 employees, Warren said the concerns are baseless.

“Concerns about the pipeline’s impact on the local water supply are unfounded,” he wrote. “Multiple pipelines, railways, and highways cross the Missouri River today, carrying hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil. Dakota Access was designed with tremendous safety factors and redundancies, including compliance with and exceeding all safety and environmental regulations.”

Yet the Standing Rock Sioux are standing their ground, and their concerns have prompted thousands of American Indians to join them and their allies in North Dakota at the Sacred Stone Camp.

“This is a prayer camp movement to save our sacred land and water and has been entirely supported by the people and the campers,” reads Gofundme.com/sacredstonecamp. “This pipeline will cross the Missouri River and the Cannonball River [a tributary of the Missouri River] … is the lifeline to many tribes and non-native[s]. When this pipeline leaks, it will destroy water and land.”

UTA English professor Kenneth Roemer, the adviser to UTA’s Native American Student Association, said he cannot recall another time when so many tribes have come together.

Hawste Wakiyan Wicasa, an organizer at the camp, told BBC on September 2 that this is “the first time the seven bands of the Sioux have come together since Little Bighorn.”

Through their donation page, Gofundme.com/sacredstonecamp/donate, Sacred Stone has raised nearly $800,000 for the thousands of men, women, and children at Sacred Stone camps.

Bluehorse believes it is not a matter of if the pipeline will leak but when.

Although the protest that Willis and Dewey attended at ETP’s Big D headquarters was peaceful, American Indians near the Sacred Stone Camp experienced something entirely different the following day. Water protectors trying to stop pipeline workers from bulldozing the remains of sacred tribal burial grounds were met by private security guards and fang-bearing guard dogs. According to news reports, six people were bitten, including a small child.

Former NASA president Stephanie Vielle, a member of the Blackfeet Nation, said the move was an effort to intimidate her people. The damage, she believes, will never go away.

“It not only destroys us on the inside,” she said, “but the [ancestral] history, we won’t be able to share that with our kids one day.”

However, the security force’s strategy backfired. The dog handlers were caught on video by Democracy Now, an independent news program. In addition, the number of water protectors and their allies at the Sacred Stone Camp swelled following the skirmish.

An arrest warrant for criminal trespassing was issued for Amy Goodman, an executive producer and host at Democracy Now.

Although Warren declined to be interviewed for this story, his spokesperson produced a memo that the ETP CEO had written to his employees after the company got swept up in the media firestorm following the dog attacks.

“We respect the Constitutional right of all assembled in North Dakota to voice their opinions for or against projects like ours,” Warren wrote. “However, threats and attacks on our employees, their families, and our contractors as well as the destruction of equipment and encroachment on private property must not be tolerated.”

Warren went on to say that the right of way for the entire pipeline has already been obtained and that the states of North Dakota, South Dakota, Illinois, and Iowa have issued satisfactory permits and approvals. Warren also pointed to several studies indicating that no historically significant sites existed along the North Dakota section of the pipeline’s route.

“If any potentially sacred objects were to be found, archaeologists, environmental inspectors, or trained construction staff are onsite throughout construction to ensure their proper care and that proper notifications are made,” he wrote.

Contrary to Warren’s memo, 4-traders.com, a stock exchange information site, reported that “a coalition of more than 1,200 archeologists, museum directors, and historians from institutions including the Smithsonian and the Association of Academic Museums and Galleries has written to the Obama administration to criticize the bulldozing.”

A second round of pipeline protests at ETP’s headquarters took place on September 24. Social media posts show water protectors marching to Warren’s multimillion-dollar Dallas mansion that day. Some carried signs that spelled out “Arrest Kelcy Warren, Not Journalists” when placed together.

******

Lujan comes from the Big Bend area, where most people use propane, he said. He wants to keep the area pipeline-free and thinks people should step back and “look at the bigger picture.”

Here’s part of it.

Over the course of 12 years, Warren and partner Davis built Energy Transfer Partners into one of the nation’s largest pipeline companies, according to Texas Monthly. However, Davis retired from the energy goliath in 2007 and is now a co-owner of the Texas Rangers baseball team.

Since last year, Warren has been serving on the Parks and Wildlife Commission as an appointee of Gov. Greg Abbott, and former Gov. Rick Perry serves on ETP’s board. Also on the ETP board is Ted Collins Jr., past president of Enron Oil and Gas, the Houston company ravaged by a widely publicized accounting scandal in 2001. The political powerhouses are part of the big picture of land protection versus oil and gas interests.

But for Robert Rivera, the bigger picture has just started to come into focus.

The Arlington city councilperson said that the record-setting Oklahoma quake caused him to take a broader perspective of the oil and gas industry. Although Rivera made it clear that he is not making any assumptions about fracking and earthquakes, he did say that the method was the first thing he thought of after North Texas was jarred by the quake’s rippling effects.

“It got me thinking more of the bigger picture,” he said.

“I wish I could go back and change them all to ‘no,’ ” he said. “Back then, it was an economic issue.”

Alan Saxe, a UTA political science professor, said economics is also a major factor in the Dakota Access pipeline controversy.

“It is a classical struggle, seen many times before,” he said. “The Indian tribes have the sympathy vote, but pipeline interests cannot be easily disposed of. There is sympathy, but the law and land rights also must be considered.”

Saxe also said the use of dogs was a flashback to the Civil Rights era.

“But this time,” he said, “it is not government against protesters but private entity.”

Following the hired-guns-with-dogs incident, a federal judge ruled that the Dakota Access pipeline could proceed, forcing the Standing Rock Sioux to take the matter to the United Nations –– Warren has voluntarily halted work on the project. For now.

In his September 13 memo, Warren stated that he plans to meet with government officials since the Department of Justice, the Department of the Army, and the Department of the Interior said that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is looking into whether it will need to “reconsider” any of its previous decisions.

“We intend to meet with officials in Washington to understand their position and reiterate our commitment to bring the Dakota Access pipeline into operation,” Warren wrote. “I am confident that as long as the government ultimately decides the fate of the project based on science and engineering, the Dakota Access pipeline will become operational, bringing a safer means of transportation to a much needed supply of oil to communities across the country.”

UTA’s Roemer said waterway issues with tribes along the Missouri River have been going on for more than half a century. Roemer spent some time as a kid on a Crow/Creek reservation in South Dakota. He talked about how he had once walked with Ruth Fire, who lived to be 104, to the top of a hill to gather firewood, but there wasn’t any. Instead, Fire pointed out over the Missouri to where she said trees and the homes of many American Indians once stood. They were wiped out by the Army Corps during the construction of dams to control natural flooding along the river. The result was that many Native-owned lands were flooded.

“Often there wasn’t enough thought about of the consequences,” he said. “There’s a whole history of problems related to the Missouri River, which is the lifeblood to many tribes.”

*****

While ETP’s pipeline may succeed, one of the tradeoffs has been that he has drawn the ire of American Indians as well as numerous environmental groups. And at least one legendary musician.

According to Forbes magazine, Warren was so inspired by ’70s singer-songwriter Jackson Browne that the energy titan named his only son Klyde. “Jackson” is Browne’s middle name. His first is Clyde.

Browne, however, is disassociating himself from Warren. How do they know each other? Browne told Indian Country Today he met Warren once while playing at his ranch. In 2007, Warren launched a record label. Music Road Records has released albums by Hal Ketchum, Levi Parham, and Jimmy Lafave, and in April 2014, a Jackson Browne tribute album.

All proceeds from Looking into You: A Tribute to Jackson Browne, Browne told Indian Country Today last month, will go to the American Indian tribes opposing the pipeline.

“I do not play for companies who defile nature or companies who attack demonstrators with trained attack dogs and pepper spray,” Browne said.

Browne’s statement has been echoed by other musicians, who also say they will not perform at Warren’s Cherokee Crossroads, an annual music festival in the Hill Country, even though festival proceeds go to children’s charities and public service organizations.

And several Denton bands recently played a fundraiser for water protector efforts.

“After a final counting of the donations, we are extremely proud to say that we raised $372.76,” Keara Soller posted on the group’s Facebook events page: “All of the donations will be going to support the legal defense of the warriors protecting land, water, and human rights.”

*****

American Indians aren’t the only groups struggling to preserve their culture.

According to Texas Monthly, Warren grew up in oil-rich East Texas. About a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Fort Worth, the East Texas Oil Museum can be found at Kilgore College. A wooden oil derrick stands next to the building that boasts more than a million annual visitors. Inside, a life-size statue of oilman H.L. Hunt greets them. According to the museum, petroleum is used in more than 6,000 products, including golf balls, duct tape, linoleum, and ballpoint pens. Furthermore, the museum “is a tribute to independent oil producers and wildcatters, to the men and women who dared to dream as they pursued the fruits of free enterprise.”

Tour guide Bobby Zager, 89, seems to possess an uncanny ability to size someone up, to determine if he or she has worked in the oilfields. Zager worked in oil himself, he said, conducting fracking at one time. He talked about how a man visiting the museum once told him, “I think you people are the ones causing the earthquakes.” In response, Zager told the man he was surprised his pastor had not approached the subject from the pulpit, since the Bible talks about earthquakes in the last days throughout the land.

“I’m glad I addressed it that way,” he said.

Zager also said that oil reserves shipped from East Texas to refineries on the East Coast helped win World War II.

In his September 13 memo, Warren wrote that he hopes his company can strengthen its “relationship with the Native American communities” as it moves forward with the project. He also said ETP plans to play by the rules and will trust the governmental process.

Yet for some, government processes and trust are not synonymous.

“Even if they did poison the whole reservation, probably nothing would happen,” former NASA chief Vielle said. “It’s almost like you can get away with anything the way the laws are on the reservation.”

Vielle, who served in the U.S. Army, said her trust was further strained when she learned that the National Guard had been activated by North Dakota Gov. Jack Dalrymple prior to the federal judge’s ruling that the pipeline could continue.

“I’ve been in the military,” she said. “In my opinion, bringing in the military against civilian people, especially protestors, violates the First Amendment.”

Vielle has visited North Dakota, and she talked about the pristine beauty of the land as well as the purity of the water.

“That is something that should be as valuable as oil,” she said.

Vielle also talked about how the government had placed her tribe on land that was difficult for them to survive on. She said after their small water source became polluted, they have had to rely on a municipal water supply.

“Water is the new oil,” she said. “It’s expensive to pay a water bill for people who are living day to day.”

Vielle will join others at the Sacred Stone Camp next week along with her boyfriend and a friend. She said she will report her experiences via YouTube. Vielle also has a Gofundme page, and she hopes to raise $3,000 to help with the trip and buy supplies for other campers. She is concerned that they may need flashlights and blankets since temperatures have dipped into the 30s at night recently.

“It is not like a campground,” she said. “This is a plot of ground. They don’t have big cities that light up the sky. It is dark.”

Dewey, who is from the Paiute Indian tribe, said UTA’s Native American Student Association wants to raise more awareness about the Dakota Access pipeline project.

“We are not a big group,” he said. “But when we come together, it just shows that we have all this pride to go out there and stand for what we believe in.”

Sunday, according to NBC, a federal court denied a request by the Standing Rock Sioux for a permanent injunction to halt the pipeline, tsaying that while “the tribe hadn’t met the strict requirements of the act to force a halt to construction, the three-judge panel said it ‘can only hope that the spirit’ of the act ‘may yet prevail.’ ”

Karen Gavis is a freelance writer and can be reached at karen.gavis@mavs.uta.edu.