Sunday night, a pair of competitions between contentious rivals took place simultaneously.

In St. Louis, Donald Trump debated Hillary Clinton. In Toronto, the Texas Rangers played baseball against the hometown Blue Jays. Both events came with a history of Vitriol punching Decorum in the face (literally, in some cases).

Sunday’s session elevated an already ugly campaign to new levels of contentiousness. Both candidates displayed an impressive mastery of each other’s scandals, with virtually no personal attack left unuttered.

The baseball contest’s background had included preening bat flips and HBPs and a Rougned Odor right cross to the jaw of Jose Bautista. Sunday night, all the principals in the drama took the field with a lot at stake, but all we saw in the potentially emotionally-charged atmosphere was a baseball game.

Baseball bested politics in the head-to-head matchup. They did not do so in the television ratings – over 100,000 more area households watched the debate across its multiple networks than watched the Rangers’ Division Series game on TBS. The sporting event did win the sportsmanship category – easily.

We think of sportsmanship as applicable to athletic contests, but its essence represents something larger. It embodies notions of civility and the honoring of agreements.

Playing a game against an opponent necessarily involves each trying to establish an unequal footing between the two combatants. By participating in the contest, however, both sides implicitly or explicitly agree to certain parameters. If you win by cheating, even if you win so much you get tired of it, you really haven’t won at all because your victory came at something other than what you’d agreed to. A game is defined by its rules.

Most sports’ rulebooks include provisions for treating foes with respect, and implied codes of conduct often go beyond what’s written down. Beyond even those strictures, many (most?) of us likely prefer to compete with someone who remains gracious in victory or defeat.

One rule of the debate was that the speakers were supposed to answer certain questions. They ignored it from the first query, veering to their prepared talking points with all possible haste. Both debaters disdained time limits on answers and prohibitions on interruptions, even when reminded of them by moderators.

The word “rule” also applies to what these persons hope to do if successful in their campaigns. Thanks in large part to bilateral efforts by the major parties to establish an imperial presidency, the chief executive has enormous power to affect people’s lives. Will the elected official follow the rules governing his or her office or will he or she cheat? Will he or she treat others with respect? Will he or she display the qualities of sportsmanship?

The Rangers are good at baseball. The Blue Jays are good at baseball. Consecutive postseason appearances by both leave little doubt of that. Would either Clinton or Trump be good at presidenting? It’s not much of a stretch to suggest the debate performances still leave a lot of questions about fitness to rule.

When a politician or athlete sets aside the qualities of sportsmanship, he or she often seeks to justify the action as advancing some greater good. A ballplayer who deceives an umpire does so to help his team win. A government official may embrace policies of official discrimination, Watergate break-ins, or eugenics based on the same theory : the end justifies the means.

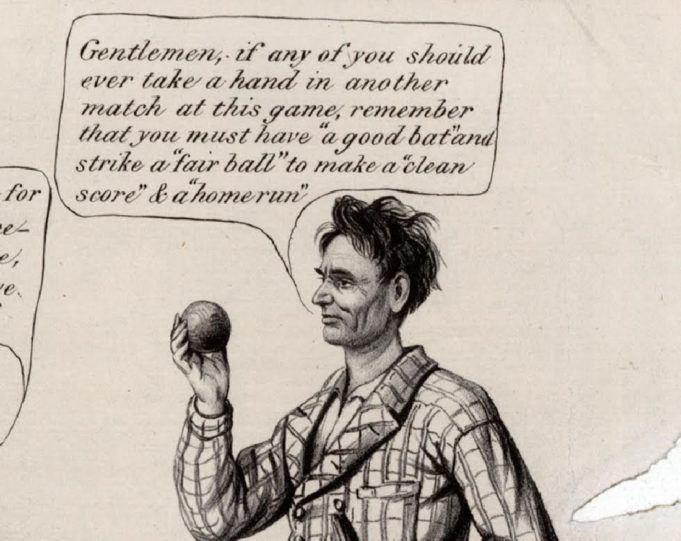

Both candidates cited the 16th president in their exchanges on Sunday. Some evidence exists that Abraham Lincoln enjoyed the then relatively new sport of baseball. Both candidates and ballplayers might do well to remember one of his remarks about the ideal outlook for a competitor.

“I am not bound to win. I am bound to be true.”