It’s been two weeks since I drove from Fort Worth to San Francisco. The trip, which also took two weeks, gave me a taste of the great American road trip, and it was an art pilgrimage of sorts. For all the times I’ve traveled west since I started making art, it’s funny that I’ve always avoided exhibitions there. It was as if I were taking a vacation away from the thing that I enjoy so much. Also, as a father, artist, and writer, sometimes trip priorities can shift. So the more I thought about the exhibits between Texas and California, and the artists like Ed Ruscha and Richard Serra who have made that journey and landscape the subject of their work, the more I looked forward to my trip. And I needed to see art outside of North Texas before the fall season of art begins here, if for nothing else than to see it with a fresh perspective.

To that end, I looked forward to our first stop along the way in Santa Fe, which would mean that I’d get to see the new installation “The House of Eternal Return” by the art collective Meow Wolf. I’d seen quite a few images from friends who’d already visited, and I was beginning to develop full-blown FOMO (fear of missing out). Plus, I wanted to continue the pilgrimage from there to museums in Los Angeles and San Francisco that I had yet to see and visit artist friends in the area.

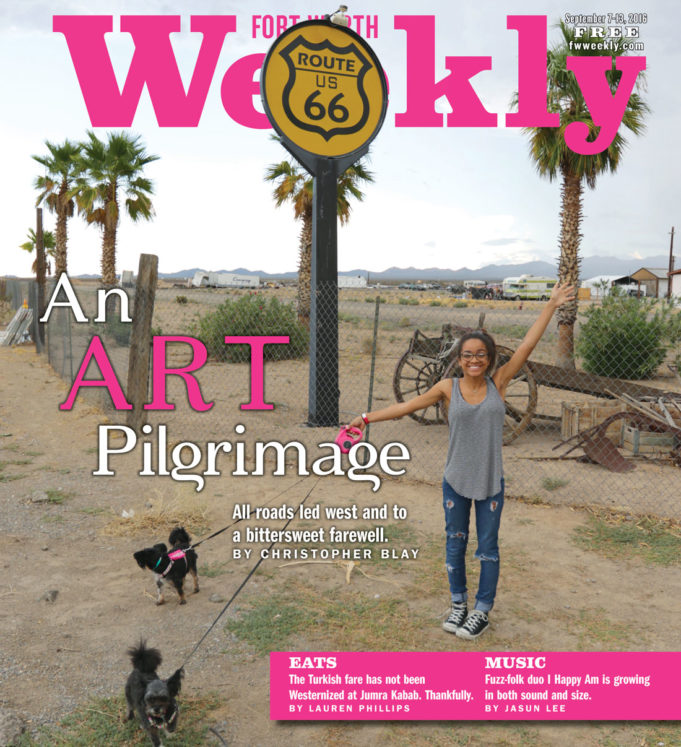

But I dreaded this trip as much as I looked forward to it. I was driving my daughter Christie to Sacramento for college along with her mom and sister. Kera and I would return to Texas, and Christie and her mom Debra would get a place together in Sacramento, with their two schnauzer-mix companions, Lullaby and Charlie.

For all these anticipated adventures, I would still be saying goodbye to my baby girl for a while because of college, and relegating our contact to holiday visits and summer road trips. As daughters of divorce and single parent households, my kiddos are pretty used to this arrangement, and so am I. But with Christie and me, it’s been a little different. She and her mom lived only 12 miles away from me, in Haltom City, for the past decade and we’ve seen each other every week since she was a child. Our favorite things to do involved going out to eat or getting coffee and just talking. And because of our frequent visits to all the area Taco Buenos, we’re semi-celebs when we go in together. We’ve also probably paid for someone’s college with the money we’ve spent at Ol’ South Pancake House. And the thought of Skype and Facetime as our only options for seeing each other regularly over the next few years was hard to swallow. Those thoughts stayed with me as we rumbled along in her little Toyota Yaris while her mom and sister followed in the U-Haul truck.

The other anxiety I felt was that of traveling across the great American West with my brown-skinned children in the bloody summer of 2016. With all the attention to police brutality spurring hashtags and slogans lately, coupled with the harsh xenophobic rhetoric from politicians in the current presidential campaign, the trepidation wasn’t unjustified. I was scared for my family, and I was scared for me. I made some excuse about not wanting to stop in Arizona because I didn’t want to spend my money there supporting Sheriff Joe Arpaio and the racially biased policing policies employed by him and other Arizona legislators. But the truth was that I feared for my family’s safety. And mine. What if we were pulled over and perceived as dangerous suspects who, like Philando Castile, “fit the description” or were screamed at and thrown to the ground like Sandra Bland and others? This may have been my own irrational sense of danger, which was the least of my kids’ concerns as they blasted Rihanna and Beyoncé on Spotify. Regardless, I just wanted to get to the Airbnb as quickly and as uneventfully as possible. To think that these fears would persist, as far removed as we are from the 1950s and ’60s, might indeed seem irrational, but as recent history has demonstrated time and again, we may not be as far removed as we think. We are certainly past the period punctuated by the 1964 murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, the civil rights organizers who met their end after being released by cops to the KKK in Mississippi. But even though we did most of our driving in the daytime, it still felt ominous in light of that history and this crazy summer.

I also thought about “The Great American Trip Road,” an installation I did at the Texas Theater in 2010 and updated a couple of years ago for WoCA Gallery in Fort Worth. The piece was inspired by my discovery of photographic slides and Super 8 movies at garage sales of families who made similar trips 50 and 60 years ago. Here were the same great vistas they experienced and documented.

However, the glaring omission of African-Americans in images from that era reminded me of how different that experience would’ve been for families like us road-tripping at the peak of its popularity in America culture.

We drove mostly uneventfully through the West Texas landscape, zipping up Highway 287 and stopping for food in Amarillo at the Coyote Bluff Café. After scarfing down their signature Burger from Hell (with jalapeños and Tabasco and Coyote Hell sauces) and finishing off with some cheese fries, we switched drivers and got back on the road. The looming storm ahead at dusk prevented us from experiencing Cadillac Ranch, the iconic Stonehenge-like car sculpture that can be seen from I-40 outside Amarillo, and engulfed us before we even noticed that we’d already missed the exit.

As the clouds darkened and the beads of rain bubbled away along the edges of where the wipers couldn’t reach them, I felt the slight tugging melancholy that was also just on the edge of where it could reach me. I started thinking about life in moments, Christie’s and mine, silly moments and made-up words that described them like “craffing”: the place between crying and laughing where every toddler lives, trying to convince themselves that they are mad but being easily distracted by something funny. How did Christie go from this to talking about the price of books and tuition?! The weather cleared just as suddenly as it had come upon us, and Christie and I both looked across at the windmills emerging like daffodils on the hills beyond the car.

We made a few more stops for gas and snacks and for Kera to curiously wander around shady gas stations trying to catch rare Pokémon. We talked about the lump in our throats and not wanting to “go there” until after the trip. Both my daughters were born on the same day, March 26, seven years apart and have developed a kindness with and a connection to each other that I am grateful to be witness to. I see this connection the most when we take our annual “Blaycations,” usually road trips, and the girls playfully gang up on me for some ridiculous reason or another. This trip it was apparently my inability to give proper directions from Google Maps. The phrase “Um, why don’t I navigate, Dad” played like a broken record every time I was in the car with either or both of them.

We reached our Super 8 motel in Santa Fe close to midnight and except for someone leaving the heater on in our room all day, and having to switch rooms, we complained about little else and called it a night.

The prospect of free breakfast had us up early, leaving us with all day to reach the Airbnb in Gallup, N.M. The plan was to have breakfast with Kera’s high school friend Bridget, who lives in Santa Fe, and then go to Meow Wolf. After that, I wanted to visit Kate River’s studio. She’d moved to Santa Fe a few years ago from Fort Worth and had a studio practice close by. So I began mapping out my art agenda.

After breakfast with Bridget, we went to explore “The House of Eternal Return.” It is the brainchild of Corvas Brinkerhoff, Vince Kadlubek, and all of the others at Meow Wolf. I met Brinkerhoff in the spring of 2013 at a backyard concert at the Austin home of Marcus Lawyer, a former Fort Worth musician and culture facilitator. This would be an unusual connection if it were anyone other than Marcus. His roots in the Fort Worth music scene touched every musician, and making connections between creative people is his staple. It’s that same intangible aura that reaches far beyond the Fort and led me into the middle of the New Mexico desert.

I knew things were about to get weird as I pulled into Meow Wolf. As part of the $2.7 million, 33,000-square-foot building leased to the art collective by Game of Thrones author George R.R. Martin, the parking lot was stalked by a larger-than-life red robot (think: The Iron Giant) that loomed over the cars and an 8-foot sculpture of a wolf that greeted visitors near the entrance. And if you were waiting for a ride in the parking lot there was seating under a giant spider sculpture that would make Louise Bourgeois’ spider jealouse.

The entrance of the cavernous installation began past the ticket counter. And after winding through a narrow corridor where a Max Headroom-like character on a TV monitor implored visitors not to do anything “radical,” we all entered the main space. We were suddenly in the yard of a two-story home, inside the building. Without giving too much away, this space-within-a-space motif plays a big role in experiencing the installation. There were doors that opened to rooms and unexpected discoveries holding clues to the mysterious disappearance of a fictitious family whose lives are part of the unfolding narrative. I was too preoccupied with the true sense of wonder and play that this installation evoked to get into solving the mystery, and I was fine with that.

Kera’s interest in manga and everything theatrical led her to a room of floor-to-ceiling wall drawings of some of her favorite characters and on her own path to discovery. She would later return with Bridget after we left to pursue our separate afternoon agendas.

Mine took me to Kate’s studio. The two-story space at Second Street Studios in Santa Fe is the artist’s home away from home. Rivers lived and worked in North Texas a decade ago, showing in small exhibitions at the Fort Worth Community Arts Center and longer established spaces like the Conduit Gallery in Dallas. But her work traveled far beyond Texas and eventually led the former Ford Family Foundation scholar to Santa Fe, where she continues to work on intricately detailed collages. The pieces are made from fragments of maps, notes, book spines, and paper scraps and relate to memory and nostalgia. Our conversation fueled my curiosity about artists and writers who had taken a similar trek out west — icons like Steinbeck, Kerouac, photographer Robert Frank, and painters Georgia O’Keeffe and Ed Ruscha. What were their motivations, and how did their work romanticize this landscape? It’s hard to imagine taking a road trip west as a writer and not thinking about Kerouac or as a painter and not recalling O’Keeffe. I left Kate’s studio and reconnected with the rest of my party for the drive to Gallup.

******

I would point out that Joe Arpaio is the sheriff of Maricopa County. The part of Arizona that Christopher Blay passed through is in Coconino County, which is located to the north and whose sheriff has not made national headlines for being racist and horrible.

I would simply reply that if you were poisoned at a McDonalds on Seminary Drive, would you stop and chow down at the McDonalds on 28th St, which is strung out along the North side, even if their teen-age cooks hadn’t be caught spitting in the secret sauce for more than 8 days and each and every brat had been Baptised?

What’s out of line here?