Thirty-eight years ago, I was shocking the bourgeoisie by making provocative movies and playing in confrontational bands with fellow film students. To borrow a romantic phrase, we were mad, bad, and dangerous to know –– mad like Jack Kerouac’s motor-mouthed hipsters, a bad influence on career-minded classmates, and dangerous to know, not because we might kick your ass but because you might get caught in a riot at one of our shows.

I’d been up to no good, artistically speaking, since I hit puberty. It just happened that during 1977 to 1981, my tendencies aligned with a zeitgeist.

Triggering this cultural tsunami was the Sex Pistols’ October 28, 1977, release of Never Mind the Bollocks and their concerts in San Antonio and Dallas in January the next year. Just about everyone I was to come to know and work with were fans of that album or attended those shows. The defiant, iconoclastic attitude of the Pistols would inform our work for years to come.

I first thought of making a film about The Doors’ lead singer after having a dream where I saw his death as a movie, shot by shot, most likely triggered by the prolonged murder scene of Rasputin from Nicholas and Alexandra. It followed that Morrison’s life should flash before his eyes as he drowned in the bathtub. Little was known about Morrison at the time. It was two years before Jerry Hopkins published No One Here Gets Out Alive and more than a decade before Oliver Stone’s The Doors. All I had was a handful of articles from teen magazines I’d collected as a kid and, from the library, a few newspaper accounts of Morrison’s arrests and trials.

From that paltry archive, plus Morrison’s poetry and lyrics, I built an outline, adding an anecdote that Sterling Morrison, former Velvet Undergrounder and adjunct professor of English at UT, told me. He had once seen his distant relative Jim Morrison at a party in Laurel Canyon wrestling another man, both of them naked, on the kitchen floor atop a pile of spaghetti.

The overriding inspiration for the bulk of the script, however, came from a single poem by Morrison: “More or less, we’re all afflicted with the psychology of the voyeur … Whenever we seek to break this spell of passivity, our actions are cruel and awkward and generally obscene … .”

Controversy over The Death of Jim Morrison began at its premiere in August 1978. It screened in rough-cut at Studio A of UT’s radio/television/film building, along with a dozen other student projects. We expected to raise some eyebrows among classmates and teachers. However, I was concerned to see children and senior citizens among those in attendance. The rough cut of Morrison, two minutes longer than it is now, was top heavy with graphic footage of pigs being slaughtered and bits of pornographic found footage. All those kids and seniors? Gone, scared, disgusted.

Regardless, excising two minutes of gore and porn went a long way to assuaging the film’s loudest critic, Edward Dmytryk.

Dymytryk was a big shot on campus. Although I’d never met him, I’d seen a few of his films on TV as a kid, like Raintree County, The Caine Mutiny, and The Young Lions. I knew his reputation as part of “The Hollywood Ten,” the blacklisted filmmakers who refused to talk to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947. I was also aware that left-wing graduate students, resentful of Dmytryk’s eventual capitulation to HUAC, had tried to block his hiring as a film prof by UT.

The night our films were shown, I heard a rumor that Dmytryk was upset by some of them, so I decided to sit in on his class the next morning. I arrived early and found the compact, handsome septuagenarian sitting on his desk with his face in his hands. He waited for the room to fill before addressing us.

“What is wrong with the youth of America today?” he asked rhetorically.

The class groaned.

With the fire of a Pentecostal preacher, he admonished us for a full hour about the lewd, violent, antisocial nihilism he’d seen onscreen the night before. He’d been so bothered, in fact, that he got on the freeway heading back to Hollywood, where, he said, there was still some decency left.

But he changed his mind.

“I decided not to abandon you,” he said. “And now I intend to set you straight, morally speaking.”

In almost every instance when Dmytryk cited a specific scene that galled him, it was from Morrison. He didn’t know that one of the perpetrators was right in front of him. But the other students knew, and it brought levity to an otherwise tedious browbeating that most of them didn’t deserve. To top it off, he was talking to the dean and other teachers about establishing a board of review to nip offensive projects in the bud.

A few minutes later in the hall, Dmytryk debated another professor, Thomas Schatz, about his censorship initiative and the relative artistic merits of my film. Schatz, a brilliant young turk from Iowa, was a big influence on most of the filmmakers in Made in Texas, exposing us to works by avant-gardists Kenneth Anger, Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, and others.

I approached and said hello. Schatz introduced me to Dmytryk as the director of the film he’d hated. Dmytryk looked stunned.

“You’re not a monster, “ he said, cognitive dissonance deflating the sails of righteous indignation.

A few weeks later, I enrolled in Dmytryk’s editing class and used it to refine and finish Morrison. Dmytryk changed his mind about the film and sponsored it for a Student Academy Award in the experimental category. With his support, Morrison won the regional division. When the national winners were announced, the experimental category was omitted. Dmytryk told me our film had won, but the academy didn’t want its name associated with it.

At the time, I tried to get the rights to the songs comprising our soundtrack –– “When the Music’s Over” by The Doors and “Valley of the Kings” by Nico –– writing to the Harry Fox Agency, a clearinghouse for sync rights. I never heard back.

Nonetheless, between 1979 and 1982, the film played regularly at festivals, repertory theaters, and punk clubs to generally good response. There were dates in Austin, Dallas, Houston, San Francisco, Toronto, Ann Arbor, Los Angeles, and most notably on October 10, 1981, at the Collective for Living Cinema in Manhattan, the event hosted by Demme.

******

All of my favs in one article: music, films, Texas (Austin that is) and the history of my youth. All this inside scoop from one who was on the cutting edge of cool. Alas, it was not me, I was always a fringe fan, so my heroes were there mixing it up. I admire those who lead with a true artist heart; who were in it for expression of the times. Throwing the American dream back in the face of established values with questions of loyalty to a facade.

So much energy and brilliance all around me, exciting stuff, to expand thoughts and powerful changes. It shaped who I am and for that I am grateful. I can look back and still get excited and provoked. I need to see these films. I need to be shocked and motivated again to see how art is reflected by culture. Or is it that artist that leads culture?

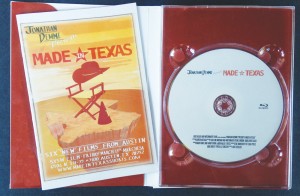

I can not wait to buy the DVD. Great article!

Great piece — superb storytelling. I saw The Death of Jim Morrison at the SFAI Cinematheque in 1981 — part of a “punk/new wave” film festival. It is the only film I truly remember from that night.

I’ve looked for it for years. Last week an old girlfriend sent me a box of my stuff found in her attic. It had a SF Chron story about the film festival and mentioned “Morrison’s” director, uh….you!

Having THAT piece of info, I tracked down this article AND the Demme/Black DVD set. It’s on the way! Can’t wait to see all the films, but especially TDOJM after 38 years. That mushroom soaked

night was one of my favorite SFAI “trips” of all-time.

Best to you, Mr. Huckabee. You made a fine-ass film.

Much obliged, Aitch. Get in touch if you like. i’m at t.huckabee@icloud.com