As he slid $12,000 in hundred-dollar bills around the table, he asked his friends to reach out and touch it, to see what that kind of wealth feels like. Steve Cardwell then asked them if they would rather have the money or the football game.

The answer was simple.

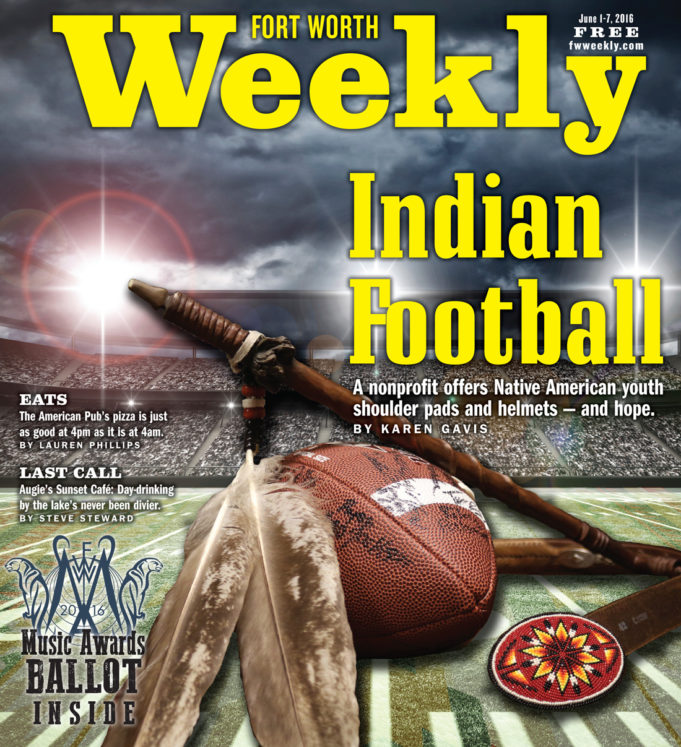

The Native American All-Star Football Classic is now in its 14th year. Set to take place on Saturday, July 2, at Maverick Stadium at the University of Texas-Arlington, the game will feature about 35 18-year-olds from all over the country.

And, true to the game’s title, all of them are Native American.

“I played football, and it changed my life,” Cardwell said. “It brought out the character in me that I didn’t know I had.”

Physical fitness is a large part of the mission of Native ReVision, a nonprofit devoted to at-risk Native American youth which Cardwell founded in 2011. At almost 16 percent, Native Americans and Alaskan Natives have the highest prevalence of age-adjusted diabetes among all racial and ethnic groups in America, according to the American Diabetes Association.

Previous Classics have been held all over the country. The 2016 version will be the fourth at Maverick Stadium. UTA leaders enjoy hosting the game to interact with the Native American community, encourage education, and provide a positive on-campus experience.

Cardwell thinks Maverick Stadium is ideal. The event needs a consistent location, he said, and since Native ReVision is located in Dallas, he felt that via Maverick Stadium he could acquire the support of local business owners throughout North Texas to help fund the event. He also knew he could count on his North Texas friends and family to volunteer.

Cardwell is personally psyched for the game, too. It wasn’t too long ago that he was thinking about giving up. But the 50-year-old has kept fighting.

“We are impacting young lives for generations to come,” he said.

******

[box_info]The 2016 Native American All-Star Football Classic

7pm Sat, July 2, at Maverick Stadium, 1307 W Mitchell St, Arlington. $10. info@nativerevision.org.[/box_info]

The Classic was originally held at Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kan., as a recruiting tool for Head Coach Eric Brock. The game ended due to a lack of support. Last year, Haskell indefinitely suspended football, a program that had had a home at Haskell since 1896, citing a lack of financial resources as the cause.

John Harjo, an assistant football coach from Oklahoma, took over the classic for a couple of years before feeling forced to end it. The reason? No money.

“I asked Harjo if he minded if I took over the game,” he said. “He eagerly said it was alright by him.”

Native ReVision was founded around the same time Cardwell took over the game.

Even with UTA’s housing and stadium discount, the Classic still costs $30,000 to put on, but it can never stop, Cardwell said.

Though Native ReVision offers various programs year-round, the Classic, Cardwell said, helps young Native American men sharpen their social and networking skills through interactions with the coaching staff and UTA personnel.

And it also lets the boys have some much needed fun.

“There is nothing more powerful than what we’re doing,” Cardwell said. “The kids are thirsting for positivity, and we’re giving it to them. We trick them into thinking they are coming for a football game, and they leave here with a whole different imprint of life, Native Americans, the world, and education.”

Classic players will stay on campus, tour the school, and the week before the game will have an opportunity to meet with advisors. Other than transportation costs, everything is provided to the players as a reward for graduating high school.

“I tell them we are all stereotyped as drunks,” Cardwell said. “We’re the lowest minority on Earth. But I tell them when they’re here, they are beautiful Native American boys. They’re not drunks.”

As Cardwell says, the closest Third World country to the United States is within U.S. borders.

In the 566 federally recognized tribes in 35 states, according to the Center for Native American Youth, unemployment is twice the average for white Americans, approximately 13 percent of homes in Indian Country lack safe drinking water and proper waste removal, and there are fewer than 3,000 tribal and federal law enforcement officers to patrol the more than 56 million acres of Indian Country.

Among Native American youth (15-24 age group), suicide is the second leading cause of death (2.5 times the national average), and violence (intentional injuries, homicide, and suicide) accounts for 75 percent of deaths for Native American youth between 12 and 20 years of age.

For some players, the game may be their first trip away from their reservation. Others may speak only their native language. Overpasses and parking garages are often new experiences. Cardwell said from the moment the players step off the airplane, he can see their minds start to expand as they soak in new possibilities.

“It’s almost like we are reaching inside them and pushing a reset button,” he said.

Maverick Stadium Director Tom Kloza, whose daughter attended Northeastern State University in the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah, Okla., said UTA’s ethnic diversity and Arlington’s location in the heart of North Texas make the stadium a perfect fit for the point of the Classic: exposing Native American youth to big city surroundings and college.

“I am glad that Maverick Stadium is a positive part of their overall experience during their week away from the reservation,” he said.

“I am glad that Maverick Stadium is a positive part of their overall experience during their week away from the reservation,” he said.

Many players raise money for airfare by selling fry bread or mowing yards.

Of the 35 participants expected this year, the Navajo Nation will send 15 men. The rest of the players will come from all across the country, and whether they are Zuni, Navajo, Nez Perce, Mississippi Choctaw, North Carolina Cherokee, or from some other nation, they are all Native American, Cardwell said.

“They get their own culture sprinkled on them when they’re here,” Cardwell said. “It’s the closest thing to a religious experience you’ll ever see. These kids think they’re cool, and then here come these kids from these reservations, and they are just blown away.”

When Antwan “Supaman” Moore played in the game two years ago, he had worked at Walmart and other places to pay for his trip. The 21-year-old Choctaw’s mother would have given him the money, he said, but he didn’t want to ask her. Raised without his father, Moore said life was good in Oklahoma, but he believes he would have landed in trouble if he had not done something different. Along with now working for Cardwell’s commercial renovations company, Brenco Industrial Services, Moore has earned a medical assistant degree and is planning to attend UTA this fall. Moore also plans to volunteer at this year’s Classic.

Cardwell, Moore said, has “done so much for me. I just want to help out. He’s like a father to me.”

Cardwell’s childhood dream was to have someone to look up to. His parents divorced when he was 8 years old. And for Cardwell, his mother Marcy, a full-blood Cheyenne, had been everything.

“She wore a cape, man,” he said. “She was just tough.”

The youngest of four boys, Cardwell, a Cheyenne tribal member, grew up in Weatherford, Okla., near his tribe’s trust lands. Cardwell’s extended family is mainly from an area near the Washita River, where in 1868 Chief Black Kettle was shot in the back and killed along with his wife, Medicine Woman, during an attack by General George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Cardwell and his family, he said, are descendants of Ben Whiteshield, one of the last peace chiefs.

Cardwell went to public school, where he played football. He immediately fell in love with the sport.

But he had to drop out of school to help pay bills. At 15, he began working the Oklahoma oil fields. At 18, he had married and started his own family.

After acquiring his “good enough” diploma in the 1980s and divorcing from his first wife, Cardwell started over in Dallas in the 1990s.

Cardwell was young, strong, and in love with work, he said, but “the fear of failure, the fear of going back to being dirt poor again” was what really motivated him.

“I’m far beyond driven,” he said. “I had the same childhood these [young football players] have. [Growing up] was like being in prison and being subdued and seeing other people doing well, and we weren’t able to, and we weren’t given the same opportunities. That leaves a mark on you, and you never forget.”

Although Cardwell has drank “enough whisky to float a battleship” in his lifetime, he said, he always worked hard. At its peak, Cardwell’s business had more than 50 employees. It now has fewer than half a dozen. The past five years have been brutal.

“I’m a lot older now,” the 50-year-old said, joking about his new AARP card. “I don’t have the energy or the ambition I had when I was younger, so I’m at peace with where we are. I don’t have much anymore, but what I do have, I’m very rich in.”

Cardwell’s oldest daughter, Kristina, 31, is a chiropractor, and his youngest, Tristen, 21, is a UTA student.

For the past 15 years, Cardwell also has been supporting his elderly mother, and while he has several Native ReVision sponsors and lots of volunteers, he works every day to see the annual event through.

Cardwell said he’s often depressed. He also says that friends and family members are worried about his health. They think he works too hard. But he says other folks spend just as much as he does on the game on stuff like hunting and golfing.

“This is what I like to do,” he said.

******

I cannot wait for this upcoming game!

Hello. Game time is 7pm as that was not mentioned. Everything else is correct. Hope see a great turnout for an even greater cause.