A two-story house on View Street inspired artist Mary Jeter to set up an easel across the street in Tandy Hills Natural Area, squeeze an assortment of paints onto her palette, and stand knee-deep in grass and wildflowers while creating a rendering of the old abode.

Before long, she was crying.

“My parents’ best friends lived in that house,” Jeter said. “They were like parents to me, and they recently passed away.”

She took a moment to compose herself before describing how they would all hike and pick wildflowers at Tandy Hills in the 1960s and 1970s.

“It was a great life over here for all those years,” Jeter said.

She moved away from the East Side in 1975 after finishing high school, but she and her husband returned 15 years later to raise their three children. The neighborhood changed. Houses aged, property values decreased, demographics morphed. In the meantime, city officials created a de facto refugee camp complete with public transportation, shelters, clinics, churches, and assorted services to handle the city’s homeless residents. And everything was planted on East Lancaster Avenue, the gateway to that part of town.

Dumping things on the East Side isn’t unprecedented. It’s tradition. Fort Worth was established near the Trinity River bluff in 1849 in what is now downtown. Development moved north, south, and west mostly. Going east meant moving downstream, meaning that everything dumped in the river in Fort Worth would float past. And don’t forget the smell. In the beginning, Fort Worth was dubbed Cowtown for real reasons rather than marketing ones. After the Civil War, beef was bringing big bucks, prompting a boon for the city’s Northside stockyards. Millions of head of cattle, sheep, and pigs took that one-way ticket to the slaughterhouses. The mix of blood, guts, and poop created a stench that could choke a skunk. Prevailing winds blew them eastward.

An informal trash dump was established near the riverbank on the East Side. Environmentally sound? No. But what the hell, at least it all flowed toward Dallas. The city’s first sewage treatment plant was established east of town for the same reason.

The East Side might have been hilly and pretty, but the city’s moneyed residents flowed in the opposite direction, making the West Side the city’s power base. Everything east of downtown was, well, that other part of town. Despite the obstacles, East Lancaster Avenue (U.S. 80) became lined with restaurants, motels, department stores, and mom-and-pop businesses. But that avenue went downhill after the turnpike/I-30 was built in the late 1950s and drew away the traffic. Business folded. Blight set in.

Need to send the city’s floodwaters somewhere? Need to plop a saltwater injection well somewhere? Need to herd the homeless somewhere?

Need a persecution complex?

Look in the direction where the sun rises each morning.

A recent drive along East Lancaster at 10 a.m. revealed people wandering in every direction on both sides. They stood in medians, jaywalked in front of traffic, waited at bus stations, panhandled for money at intersections, and relaxed under shade trees and on steps and curbs, many of them carrying small suitcases or just clothes and belongings wrapped in blankets. A blind man ambled slowly along a sidewalk, his cane feeling for obstacles ahead. A stooped, elderly man wore a heavy backpack while pushing an elderly woman in a wheelchair. A young man in baggy pants stood nearby fondling his own genitals. Closer to downtown, under a highway bridge, a police officer told a sleepy looking woman with a large suitcase to move along.

Jeter and her friends carpooled their children to other parts of town from Meadowbrook, one of the East Side’s largest neighborhoods, to enroll them into special interest schools.

The Meadowbrook schools weren’t competing as well, she said. “We ultimately moved.”

Businesses fled as well. And are still fleeing.

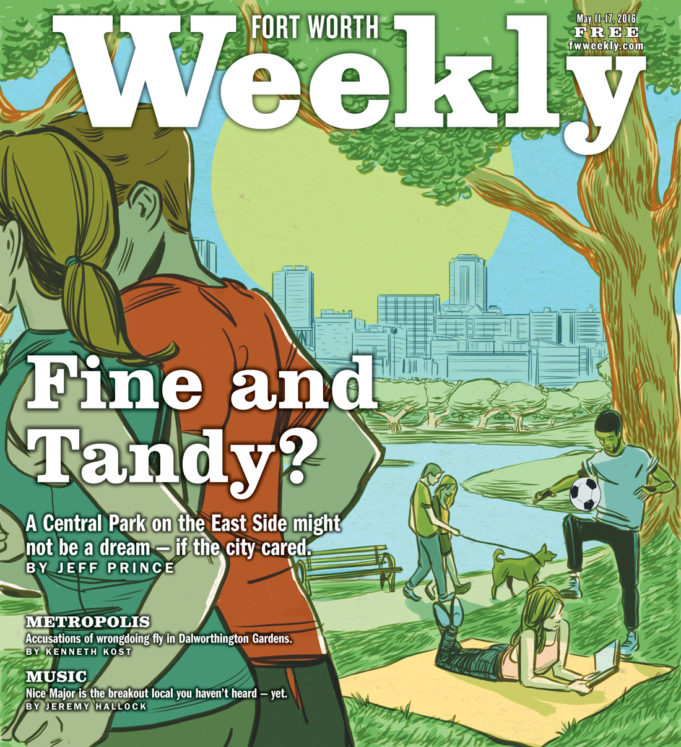

Jeter returned to this overlooked part of town on a recent Saturday to practice painting amid the wildflowers that splashed colors on the flowing terrain. Tandy Hills remains one of the city’s most impressive parks –– 160 acres of wild, wooded prairie land just south of I-30 near Oakland Boulevard. Residents have fought for years to protect and invigorate this place of splendor even as surrounding neighborhoods struggle against decline.

“It’s gone a little downhill,” Jeter said. “The beautiful homes have gotten a little run down. The city maybe doesn’t pay enough attention to the East Side as far as beautification. I’m not criticizing anyone, but it does seem like the forgotten part of town.”

And there it is. The complaint that almost always surfaces when discussing the East Side –– city officials don’t care about this part of town. Never have, still don’t. People trot out that complaint so often you wonder if they’re being paranoid. But like the saying goes, you’re not paranoid if it’s true.

Let’s see, the city is currently considering a zoning change to allow a concrete recycling plant to open near White Lake Hills, an exclusive neighborhood that is already putting up with Chesapeake Energy’s saltwater injection wells near the intersection of Oakland Boulevard and East 1st Street. One of the city’s oldest businesses, Marshall Grain, is relocating to Grapevine. Walmart’s Neighborhood Market at 6513 Meadowbrook Dr. is closing after 13 years. A drive down East Lancaster Avenue reveals many fading and shuttered storefronts. Some of the houses in Poly, Meadowbrook, and other Eastside neighborhoods are in shambles.

The key to the East Side’s revival might be found underneath Jeter’s feet. Advocates say Tandy Hills could serve as a Central Park-like selling point to attract potential homeowners and developers to the surrounding areas. Mayor Betsy Price floated the idea of linking Tandy Hills to a nearby undeveloped plot of land and then linking both of those places to Gateway Park on the north side of I-30 via hike and bike trails. Together, the three parcels would provide a beautiful green space that would dwarf Central Park in size. Link all that to the thriving Texas Wesleyan University campus nearby, and perhaps a synergy could be created to make this a happening place instead of a hapless one.

There is no shortage of residents and activists pushing for renewal, including a prodigal son with a historic last name. Two years ago, John Tandy returned to the city after a long absence and settled into the family home in Meadowbrook bordered by Lancaster Avenue on the south, I-30 on the north, Riverside Drive on the west, and Loop 820 on the east.

The area’s present and the future might not be as dire as some people think, he said.

“The East Side is a place waiting to be discovered,” Tandy said. “The opportunity is here.”

******

Are you trying to claim that most of the stockyards stench blew eastward? I’m not buying it, slick.

You loose Dave…both the stockyards bedraggled aroma and our cities persistent sewage perfume settled in on the East Side. The aroma, most every day, back in the day, would gag a buzzard. True. For some reason, Black folks rode in the back of our cities buses too back then, just the way things was. I headed out to the East Side pretty often to get Bar-B-Q and beer in Stop Six back then. A Black fellow named Sonny worked six days weekly fixing flats, and washing cars, and keeping the Rest Rooms tidy for my Daddy at his Gulf filling station. Sonny got $40 weekly (before taxes) for six days, ten hours daily. He was a good guy and honest and worked like a mule. I would take him home from work on Friday, buy some Bar-B-Q at a falling-down shack of a place, and Sonny would take care of gathering up a six-pack of Pearl beer for me at the same joint. I’m sorry, back to what I was saying…the packing house odor covered the East Side and it was pretty rich, I’m telling you what.

It’s 10:48pm 5/15….who do we pay to get moderated? Whose on first? What the hell?