Thomas Hart Benton was such a major American artist and muralist during the 1930s and 1940s that some consider him America’s version of Diego Rivera. Benton’s large, populist images are amazing to see, including the Hollywood scenes currently on display at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Organized by the Peabody Essex Museum of Massachusetts, the touring exhibit American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood runs through the end of the month.

Benton’s connections to Hollywood and his home state of Missouri are well documented. What isn’t well known –– even the Carter folks seemed mostly unaware –– is the deep connection between Benton and the late John Paxton, a Fort Worth businessman and the father of actor Bill Paxton.

“I remember Benton when I was a boy,” Bill said. “He would come and stay at our house in Fort Worth. My dad knew him from boyhood.”

Benton, born in 1889, was an acclaimed artist by 1937, when Life magazine paid him to go to Hollywood and depict the film industry in a series of paintings. Many of the results hang in the Carter exhibit.

One of them, however, hangs in Bill Paxton’s California digs.

“I had the good fortune to buy one from the Hollywood series, called ‘Hollywood Projection Room,’ ” Bill said. “It took me a year to pay it off.”

He would have loaned it to the Carter museum for the show, he said, if he had been asked.

“It would have been a good one to include,” he said.

The problem is, few people know about the connection between Benton, the Paxtons, and Fort Worth. John Paxton grew up in Missouri, and his well-to-do family moved next door to Benton in Kansas City in the 1930s. John was 12 at the time and had recently become interested in art. So it was a coup to suddenly be living next door to “the greatest living artist of his time,” Bill said.

“Benton is very accessible even to the lay person,” Bill said. “You don’t have to be a sophisticate to appreciate his work. It’s dynamic. It’s got color. There is storytelling in all of his work. He’s an American painter who defined the American landscape.”

Benton loved the common man. He once said he’d rather have his paintings hang in a brothel than the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

“Benton went out among the people,” Bill continued. “He’d go into the fields with the migrant workers, or the revival tents, or go up in the mountains and live with the hillbillies. He hitchhiked and walked all over America just to find subjects.”

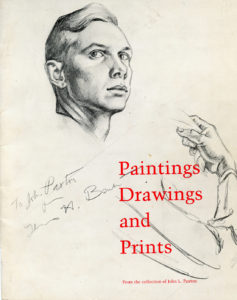

World War II drew Americans into the fray, including John Paxton, who served as a radio operator in the Air Force. He was home on leave in Kansas City when Benton asked him to pose for a portrait sketch. Benton had been watching troops board a ship one day and noticed that each soldier would take a quick look back at shore before loading. Benton envisioned a painting and wanted John Paxton’s face depicted on the soldier looking back. John was about 22 at the time.

“That picture hung in the Pentagon for many years,” Bill said. “It’s an ominous painting, these men getting on a ship at night, going to some hell hole. The guy is looking back … that expression is neutral enough so that you can read what you want into it. The drama of the painting is certainly evident.”

Now, that painting is hanging at the Carter. But there’s even more to the story.

After the war, John moved to Fort Worth to run a branch of Paxton Lumber Company. He and his wife, Mary Lou, raised a family here, and a Benton painting hung above the mantel in their living room for many years. Benton was often asked to visit colleges and teach art techniques to students. He would stay for days on end at the Paxton home on Indian Creek Drive near Shady Oaks Country Club. A helicopter carrying Benton would drop down on the 11th fairway to pick him up and drop him off.

Bill Paxton was still a boy but remembers hanging out with the old artist during his visits to Cowtown.

“He enjoyed copious amounts of bourbon,” Bill recalled with a smile.

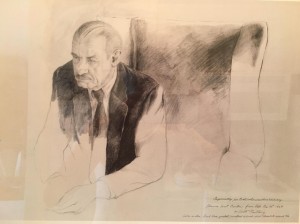

John Paxton was friendly with twin brothers Scott and Stuart Gentling, two of Fort Worth’s most successful painters. Scott Gentling, only about 22 at the time, asked to come by the Paxton house one day and sketch a portrait of the iconic Benton. Gentling was nervous and still hadn’t finished two hours later by the time Benton tired of posing.

“It was a beautiful portrait,” Bill said.

Gentling wrote an inscription on the drawing and gave it to a young Bill, who still has the piece hanging in his house. “Especially for Bill, who was there that day,” Gentling wrote. “Thomas Hart Benton from life. Dec. 18, 1964. Color notes: dark blue jacket, mustard colored shirt, chocolate colored tie.”

Bill was 14 the last time he saw Benton. The Paxtons had traveled to Kansas City to visit his grandmother at the old family house, and they paid a visit to the Bentons next door on Christmas Eve.

“We went over to the Bentons to have drinks, and I got to drink some Jack Daniel’s and Coke, which was a big deal,” Bill said. “He was not a tall man but he had great stature. He died a couple years later. He was a towering figure in the art world, although he had his critics.”

John Paxton hit hard times temporarily in the 1970s. Selling his favorite Benton painting that hung above the mantel was excruciating for him, Bill said.

“He’d gotten himself into debt, and the interest rates under President Carter went to 20 percent and even higher, I think,” Bill recalled. “My dad was having to give the bank a substantial amount of money just to roll over the debt.”

John and Mary Lou Paxton hung on to other Benton works, along with many paintings by other prominent artists that were donated to the Nevada Museum of Art after Paxton’s death in 2011.

“My dad was very proud of his friendship and association with Tom Benton,” Bill Paxton said. “That’s what he called him –– Tom. One of the greatest autobiographies I’ve ever read was by Benton called An Artist in America. He was political, philosophical, a real Renaissance man.”

Thank you, Jeff, well done. I remember Scott returning from the Paxtons that day, portfolio in hand.

Great work, Jeff!