The Impressionist painters were still around when cinema first appeared on the scene, and over the following decades the new art form slowly convinced people that it deserved to be taken seriously as both visual and intellectual fodder. To me, it seems that not enough scholarship has been done about what impact the advent of cinema had on the more established visual arts. Helping to redress this is the Amon Carter Museum of American Art’s new exhibit, American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood, an account of the regionalist painter’s decades-long affiliation with the nascent industry. Organized by the Peabody Essex Museum of Salem, Mass., the show is the first major Benton retrospective in more than 25 years and a cinephile-friendly introduction to this muralist who was considered a giant of American art in his time.

The Missouri-born artist first became acquainted with the medium when he took a bill-paying job painting sets for silent movies being filmed in Fort Lee, N.J. In addition to Benton’s artworks, the show includes video monitors showing numerous clips from films of the period that influenced his paintings and drawings even after he made his reputation. The panels of his series American Historical Epic, monumental paintings depicting our nation’s history that includes slavery and the genocide against Native Americans, are paired up with a clip from Clarence Brown’s 1920 silent adaptation of The Last of the Mohicans, a film that used white actors to portray the savage Indians. Not only does the juxtaposition underscore the realities that Benton determined to show his audience, it also reminds us that the practice of “whitewashing” in movies goes back more than 100 years.

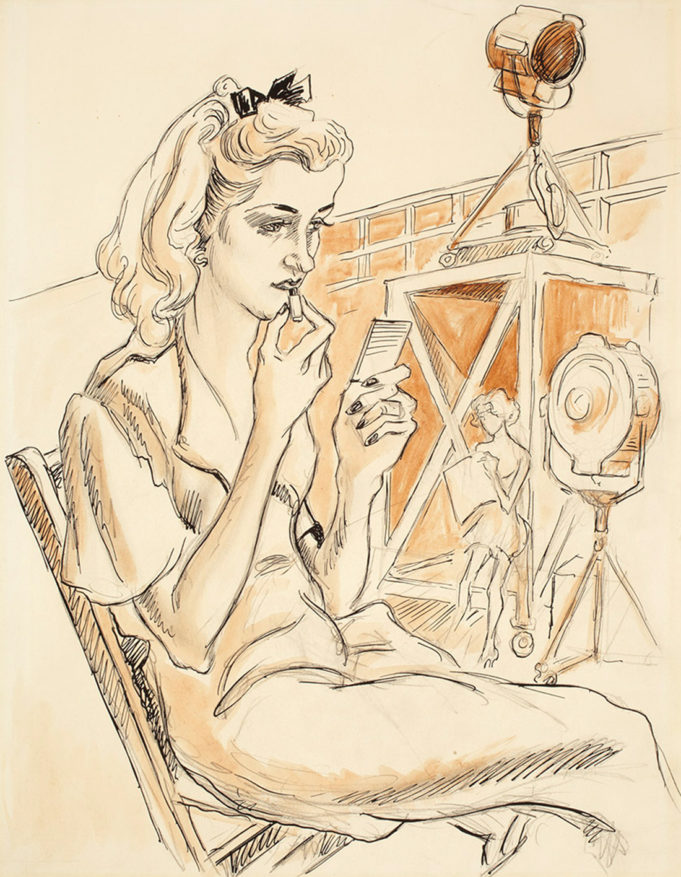

In 1937, Life magazine commissioned Benton to travel to Hollywood and execute paintings and drawings of what he saw. He witnessed the filming of In Old Chicago, and the exhibit contains a clip from this musical that was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar that year and is all but forgotten now. Tinseltown has a long tradition of films that give fans the sense of being privy to the drama behind the scenes, so this same section also includes a clip from Tay Garnett’s comedy Stand-In, showing an actress being pelted with fake snow as she films a mountain scene inside a studio. In the same spirit, Benton sketched craftsmen, musicians, and dealmakers at work — one work on paper called “Member of the Chorus” depicts a pretty actress lounging in a chair on the set between takes, applying lipstick while checking herself in a pocket mirror. His painting “Hollywood” places a shapely actress in a two-piece bathing suit at its center, but your eye is drawn to the artful chaos going on around her as crew members place equipment and other films are being shot elsewhere in the frame.

Benton would dismiss the film industry as “an economically conditioned art” that year, but it didn’t keep him from producing character sketches and the poster for John Ford’s 1940 prestige drama The Grapes of Wrath, which appear in the show along with an appropriate clip. He went his own way, though, when World War II started, as he painted his Year of Peril series to urge viewers to participate in the war effort. The exhibit makes note of how the graphic violence in these paintings wouldn’t have passed muster with Hollywood’s sanitized propaganda films. It does not, however, make sufficient note of the racial stereotypes at work in his war paintings, especially in the hairless, buck-toothed, naked Japanese soldier being killed in “Exterminate!” and piercing the side of a crucified Christ in “Again.” These weren’t unusual for the time, but it does show that Benton’s racial politics were progressive only to a point. Ironically, the clip accompanying the World War II paintings from the documentary The Negro Soldier (directed by U.S. Army Capt. Stuart Heisler) is arguably more enlightened in its depiction of African-American servicemen than Benton’s own painting entitled “Negro Soldier.”

Cannily, the exhibit displays clips from Jacques Tourneur’s Canyon Passage and Anthony Mann’s The Far Country in parallel with Benton’s later landscapes, which grew more picturesque as the movies grew more panoramic in their depiction of Western natural scenery. Even with that, there’s a lot less of interest in this later stage of Benton’s art, when he withdrew from the changing art world and painted mostly works of inoffensive nostalgia. His portrait of Burt Lancaster for the 1955 Western The Kentuckian was used as the movie’s poster, and it’s pure kitsch, manliness taken to the realm of unintentional self-parody. (The actor liked the art, though, owning the painting until his death.) This fits with the theme of the exhibit, but the real value of American Epics is excavating this artist who got washed into obscurity by the 20th century’s vogue for abstraction and showing us the eye for drama and craggy dynamicism that made him famous, and which he learned at least partially from the movies.

[box_info]American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood

Thru May 1. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd, FW. Free. 817-738-1933.[/box_info]