Dallas resident Itasca Thompson passed by plenty of animal control shelters on her drive to Fort Worth to adopt two Chihuahua puppies on a recent afternoon. Most North Texas municipalities rely on taxpayer-funded animal pounds. Several dozen are scattered around. They co-exist with nonprofit shelters, including the Humane Society and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Many shelters team up with large retailers such as PetSmart to create offsite adoption centers.

Fort Worth shelter staff get help from a small army of nonprofit directors and volunteers coming from the Humane Society, Mid-Cities Community Cats, Panther City Feral Cat Coalition, and many other groups. The volunteers do everything, from dropping off and picking up trap-neuter-release designated cats from the city shelter to collecting and donating bedding material and offering subsidized or free neuter and spay operations.

Thompson searched the websites of several shelters before deciding Fort Worth’s was best. She liked the low cost to adopt ($49 for dogs, $25 for cats), which includes various shots and sterilization.

“I’ve been to the animal shelter out in Plano, and this compares well to it,” she said. “It’s pretty clean. All in all, pretty good.”

“Pretty good” is a grand compliment compared to some of the feedback being flung in the shelter’s direction these days.

Shelter leaders say they’re doing the best they can with a limited staff and budget to care for more than 20,000 animals a year. Code Compliance Director Brandon Bennett, who oversees the shelter, points to the steadily increasing number of animals being adopted into homes rather than being killed. The city’s live release rate was 88 percent as of November 30. That means only 12 percent of shelter animals were euthanized or otherwise died this year. The death rate was 33 percent in 2012 and more than 60 percent in 2010, indicating a steady improvement in recent years. Texas Health Services has graded the shelter as satisfactory after inspections in recent years.

During Bennett’s tenure, the shelter has opened a medical treatment ward and a second adoption center, and taken ownership of a pet disaster relief trailer donated by local dog clubs. Bennett hired an additional three animal control officers last year, increasing the number of animal control officers to 21 and the number of strays being captured by about 100 a week. The officers patrol 345 square miles.

Under his guidance, the shelter has added veterinarian and kennel owner Tim Morton to help manage things. They’ve created several effective programs that improve animal care and adoption rates, and they have improved the shelter site by adding outdoor kennels and play areas.

Animal lovers, however, can be a hard bunch to please. Staff shortages, budget limitations, and the overwhelming number of animals to deal with are seldom suitable excuses for not giving the best care to every animal seized. Animal advocates understand the challenges of running a shelter. They’re eager to help. But some are backing away after seeing how the sausage is made.

Hurst resident Kim Leach, a Shelby supporter, began volunteering this past summer at the Fort Worth Animal Care and Control, a sprawling, cinder-block building with a maze of hallways, rooms, and cages located in an industrial district in southeast Fort Worth. No more. She’s seen feral kittens sterilized and released back into the wild too soon. She’s given cats medicines that seem to be “watered down” and have little effect. The staff appears overwhelmed at times. The shelter has gone without a vet on the premises for spells. Volunteers and rescuers bicker among themselves and with staff, and it seems like most refuse to compromise. And now superintendent Shelby and some of her staff who tried to change things have been shoved into employment limbo, Leach said.

“I’m done trying to help the shelter,” she said. “I wish them the best, but I’ve had nothing but bad results from them.”

The City Council created the task force in November, and the new group met for the first time last week to tour the shelter, speak with staff, and listen to residents speak their minds.

But before the meeting even began, a member of the Animal Shelter Advisory Committee expressed quiet concern to the Fort Worth Weekly. She’s part of the seven-member group formed in 1994 to make recommendations to improve efficiency and cost effectiveness. She asked not to be identified for this story, but she said two of the new task force members had ties to shelter leaders, casting doubt on those members’ independence.

Another advisory board member had told the Weekly a few days earlier that Shelby was put on leave for wanting to make changes that would improve animal care. The task force wasn’t looking into personnel issues, only services and procedures. Bennett and Morton, the board member said, have their way of doing things and don’t appear overly interested in receiving suggestions. She doubted either of them was much interested in what the task force had to say. Her primary complaint is that shelter staff euthanizes too many animals because “it’s less hassle.”

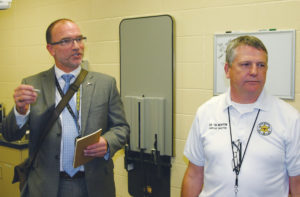

Bennett and Morton led the tour, and both were engaging and well spoken. They appeared to care about the animals under their watch, occasionally stopping to scratch an ear here and a muzzle there during the tour. Hundreds of animals in cages watched the process with sad eyes.

Bennett hears all the complaints and accusations, and he’s skillful at discussing (and often deflecting) them. One of the situations that allegedly contributed to some of the employees being put on leaves of absence involved Joel Akin, who routinely performed surgeries as a contracted vet. Some staffers and volunteers described Akin as a sub-par surgeon with a drinking problem and a questionable record with the Texas Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners. Between 1999 and 2014, the state board reprimanded Akin four times for failing to obtain required continuing education, twice for defaulting on child support, and once for practicing with an expired license. His license was suspended for two years in June 2014.

Akin’s criminal record contains misdemeanor assault, resisting arrest, harassment, criminal trespassing, and drunken driving convictions between 2002 and 2012. Concerned staffers and volunteers accused him of two botched surgeries in one day that led to the deaths of two animals. But, at first, Bennett and Morton defended Akin. At least one of the staffers who complained is now on a leave of absence.

Bennett, who oversees 350 city employees in several departments, can’t cover the situation in depth because it involves personnel issues and confidentiality requirements. But he told the Weekly that an employee twice accused Akin of being drunk on the job. The second time, Bennett said he quarantined Akin at the shelter. A city health employee performed a toxicology test on the vet that revealed no alcohol in his system, Bennett said.

Bennett said Akin had a disability that sometimes caused him to get dizzy and slur his speech but that he was a skilled vet. None of his infractions with the state board involved poor surgery techniques. As for the two dogs that died after alleged botched surgeries, both were sent to Texas A&M University for independent autopsies. Lab reports do not clearly determine the cause of death in either dog but show both dogs had bad hearts and that one suffered heartworm disease. These factors likely led to “anesthetic death” since no known complications arose during surgery and neither pet woke up afterward.

Bennett fired Akin recently but not because of surgical lapses –– the vet posted violent, anti-Islamic rhetoric on his Facebook page after last month’s ISIS attacks on Paris.

On No Kill Fort Worth’s Facebook page, Akin is described as the “butcher vet” along with claims he left one of the dogs on a table with its intestines hanging out. Bennett said the dog had chewed away the sutures on his stomach after a surgery and that a vet other than Akin had done the operation. Bennett said he’s discouraged his staff from getting into verbal wars in the comments sections on No Kill Fort Worth or other sites that publish critical or erroneous accusations.

Under Bennett, the shelter has reduced its kill rate from about 70 percent to less than 20 percent. Part of that decrease shows that vets are saving more animals that come to the shelter with medical problems.

“The fact that we’re down to the last 12 to 20 percent of animals being euthanized, these are the higher risk animals, which means we should expect more complications,” he said.

The national standard for no-kill designations is for shelters to release 90 percent or more of its animals. It’s a difficult percentage to reach. City shelters tend to take in most animals regardless of their health. Austin, relying on public-private partnerships, met the 90 percent standard in 2011 and has maintained it ever since, setting an example for large cities. Fort Worth has been slowly moving in that direction ever since. Still, some local activists question the city’s numbers, particularly since feral kittens are released live, leaving activists to wonder how many die later, uncounted.

Human Society records show that shelters nationwide handle on average about 30 animals per 1,000 people. Based on Fort Worth’s population of 800,000, that would create an intake amount of 24,000 animals per year. The city’s projection of about 20,000 animals this year shows Fort Worth falls below the national average, even as the animal control center struggles to keep up.

“Every shelter in Texas is full,” Watkins said. “There’s no room in any shelters or rescues. The whole system is overwhelmed every day, 365 days a year. None of the irresponsible [pet owners] are held accountable.”

While Bennett can’t talk specifically about Shelby’s employment status due to personnel confidentiality, he said he harbors no ill will toward her and did not discipline her.

“To talk about what’s going on and stuff is not fair” to Shelby, Bennett said. “She is a good person. Of all the people I’ve met over the years, I think she is one of the most caring people when it comes to animals. I think in the end of the day this is all going to come out in the wash and people will see that this isn’t what they think it is.”

It’s possible that Shelby’s position was impacted by the city’s classification and compensation study released in June. The pay study looked at employees’ salaries and job classifications and compared them to the prevailing job market. Some employees saw their titles and salaries changed.

“This hit my department,” Bennett said without referring to Shelby. “It hit all the departments. We’ve had to adjust.”

Shelby has many supporters, including the person who hired her –– Bennett.

“If [Shelby] decides to leave, it is her choice,” he said. “She is not under threat.”

One of Bennett’s strengths is soliciting independent funding for the shelter. The city terminated hundreds of job positions after the recession in 2008 and didn’t increase taxes or fees. Departments had to do more with less. Bennett adopted a rescue dog named Henry in 2011 and turned the pooch into a cause célèbre, helping to raise $2 million for shelter programs –– the annual budget is about $3 million.

The boisterous advocates appreciate the improvements but still aren’t satisfied. Animal lovers such as Leach and others accuse the shelter of releasing feral kittens back into the wild too early. Their chances of survival might be slim, but the shelter can apply those numbers toward its 80-percent save rate.

Feral kittens are often so wild they don’t make suitable pets, so they’re sterilized and released.

“What you see in the real world is younger kittens that are being spayed and neutered, but I agree, you can’t put them out on the street” too early, Bennett said.

Just because some advocates request (or demand) changes that aren’t implemented doesn’t mean shelter staff don’t care or can’t accept constructive criticism.

“Some people think in the absence of perfection, it’s chaos, and it’s not,” Bennett said. “We recognize we are not perfect. If you have recommendations for change, then share it with us. Look at our live release rate. That didn’t go up over time because we weren’t changing.”

******

Sissy is sassys sister not her aunt and we did have to take her back from there previous owners because they apparently didn’t know how to de worm a dog.they did however have sissy fixed where now she can’t have puppy’s.both parents of sissy and sassy are full blooded pit bull .my girlfriends dog is the blueheiler that was tied up who needs to be fixed.sassy won’t be getting fixed till her milk sacks are dragging the ground.but the next litters daddy will be this hundred pound blue gotti pit I’ve had my eye on.bet that!

Suzette Watkins is the militant activist behind the loosly followed ‘No kill Fort Worth’ page on Facebook. Rather than try to work within the system to bring a resolution to alleged problems, the Riverside Kennel owner bullies people online, lying and amplifying issues to the point of making inaccurate libelous statements. Her ‘followers’ are blind and believe everything she says hook line and sinker, which says a lot about them too. Check her record with the City, you’ll find she and Riverside Kennel aren’t as lily white as she’d like you to believe. (An arrest for Public Intoxication at the Rainbow Lounge and various Animal Cruelty complaints for starters) I’m all for animal welfare, but not for someone who revels in tearing apart individuals and organizations while hiding behind her computer.

I would encourage you to do more research. You can pull citation numbers by violation. So I’m curious who stated other wise. 810 – No rabies tag displayed canine, 812 – No city tag displayed canine, 815 – Not restrained canine, 837-01 Failure to provide food, 837-02 Failure to proved water, 837-03 Failure to provide shelter, 837-04 Failure to provide vet care, 838-13 No intact pet permit female dog/cat, 838-14 No intact pet permit male dog/cat. The municipal court can provide the number of citations issued….. Interesting how Brandon won’t comment when he might look like the bully he is, but has no problem throwing Akin under the bus to appear politically correct. “Bennett fired Akin recently but not because of surgical lapses –– the vet posted violent, anti-Islamic rhetoric on his Facebook page after last month’s ISIS attacks on Paris.”

… Though I do not agree with the nastiness of the comments made by Akin on his FB page I thought we had the right to free speech. Akin was fired when his license was suspended. He was no longer of any use to them so he had to go. They kept Akin because he was cheap labor compared to other veterinarians. You get what you pay for and the increase of post-op surgery complications was the result. The task force is a farce. The city is only going through the motions to appear they are looking into things. Brandon and the city can brag about live release numbers all they want. Numbers can easily be manipulated. Too many animals are suffering at the shelter in the name of live release numbers.

Suzette Watkins is a farce. She tops the list of do not return call lists with City Administrators/Police because of the number of outrageous claims she makes on a daily basis. I know people who have worked for her over at Riverside Kennel and quit because of the way animals are manhandled while in her care. This woman writes in 3rd person on her No-Kill Website to make people think their is indeed a board. There is no board. It’s Watkins and Watkins alone making allegations on line and calling in complaints keeping Police and Animal Control from doing real work. Next time, check into the background of the person you are trying to make into a Saint. This woman is clearly the farthest thing from that.