Jenkins appears a bit retro himself as we settle into a back table at Shipping & Receiving on a recent afternoon. The slicked-back hair and tight Wrangler jeans and denim shirt show his Weatherford roots. Jenkins and I begin discussing the studio when a pretty young woman walks up, leans over, and kisses him. Then she walks away.

“Do y’all know each other?” I ask.

“That’s my girlfriend.”

Could this segue be any more perfect? Jenkins’ girlfriend and Wrangler jeans play major roles in the legend of how Jenkins and Bridges met. Fort Worth Weekly’s Anthony Mariani was first to publish the anecdote (“Wonderful World,” Aug. 27, 2014).

Er, uh, except the anecdote involves an old girlfriend. Jenkins hesitates to rehash that part of the tale, what with his new girlfriend floating in the near vicinity. But the story is true, he says. News media have rehashed the tale many times: The girlfriend notices Bridges, a young black man, wearing the same tight Wrangler blue jeans as Jenkins, and starts a conversation. Jenkins arrives a short time later, and they all hang out and talk and listen to music. Bridges never mentions he’s a singer.

A week later, Jenkins visits Magnolia Motor Lounge to watch the Quaker City Night Hawks perform. Bridges gets on stage during a band break and sings a few songs on an acoustic guitar.

“I remembered seeing him from the week before,” Jenkins says. “Hearing him play music, I was like, ‘Oh, wow. This is interesting.’ I approached him and asked if he’d be interested in recording any of his music because it was really speaking to me.”

Bridges had been washing dishes earlier in the evening at a local restaurant.

Jenkins and Block grabbed pieces from their collection of vintage recording gear they’d been hoarding for just such an occasion and spent a couple days setting up a studio. They wanted an old-time sound and vibe to match Bridges’ musical style, which is reminiscent of Sam Cooke-era soul and gospel.

“My plan with [Block] was to get together with friends and learn and experiment with recording someone,” Jenkins says. “Leon’s sound and idea were going to fit really easily with what we’d talked about doing.”

Bridges was broke and couldn’t pay. No problem. Jenkins wasn’t asking for money. He just wanted Bridges to own a good demo of his music.

“I told him, ‘I love music and love what you’re doing. I feel like I know how that’s supposed to sound on record, and I wanted to provide the perfect backing to it,’ ” Jenkins said. “It was dumb curiosity. We said, ‘Shit, let’s just do this.’ We never started it with the intention of this is going to be Leon Bridges’ band or jumpstart his career.”

The generosity had just begun. The established indie-rock stars Jenkins and Block called on their Fort Worth musician friends for help. The Orbans’ guitarist Kenny Wayne Hollingsworth and former bassist Cliff Wright loaned their talents, along with multi-instrumentalist Andrew Skates of the Quaker City Night Hawks and saxophonist Jeff Dazey, formerly of the Josh Weathers Band.

Jenkins and Block had done plenty of home recording but hadn’t produced another artist. (Block’s wife was expecting a baby at any time during interviews for this story, and he was unavailable.) They set up the studio in two days and recorded a handful of songs over the next four days. They attempted isolating the amplifiers by using blankets, clotheslines, and bungee cords. No tracking room, no headphones, no isolated control booth. The makeshift studio resembled a hobo camp. They worked up song arrangements, although many of the musical performances were spontaneous.

They uploaded a couple of songs to Soundcloud, and White Denim’s manager sent links to Gorilla vs. Bear, a Texas-based music blog. The clicks went wild, other blog sites posted links, and “Coming Home” would soon top a million hits.

The song was not only performed in retro style, but the recording itself was a throwback. Modern recording often involves musicians overdubbing their parts while listening through headphones to the other musicians’ previously recorded parts. The method is more cut and paste than rock ’n’ roll. Jenkins and Block used analog equipment that was decades old. The reel-to-reel tape machine had once been used to record the Grateful Dead.

Listeners could hear the light hiss of the tape. Consciously or subconsciously, they could feel how the instruments and vocals bled into one another’s microphones, which happens when band members play together at the same time.

“They feel the energy and the excitement,” Jenkins says. “That’s what we were feeling as we were recording it. It’s cool that it was translating onto the recordings.”

******

The new studio is still a whir of activity, with audio equipment draped in plastic covers to keep away the sawdust. The owners were happy to show a reporter the work in progress but asked that no photos be taken. They want the first published photos to show the finished product.

The three-story brick building that houses Shipping & Receiving also includes offices, apartments, and empty spaces on the ground floor. Bridges’ first album was recorded in the same room where the Weekly held this year’s Music Awards ceremony. The new studio is being built in an adjacent room. The design calls for 1,000 square feet of studio space for the musicians to perform, along with 700 square feet of space upstairs for the engineering and green room. Second-floor engineering rooms are rare in the United States, Suffolk says in his British accent.

“Everyone in London has second-floor control rooms because we have basements,” he says. “It’s looking to get a complete bird’s eye view, and it feels grand. As a designer, it’s all about art and design. You’ve got to have that feeling of excitement when you go into a studio.”

The hobo camp recording worked out well enough for the first Bridges album, but Jenkins, Block, and Vivion were ready to push forward with their plan to open a real studio. Vivion is managing the studio while Jenkins and Block are out touring with Bridges. And what a tour. In the past year, the 26-year-old singer-songwriter has seen his title track make Spotify’s list of Top 10 Most Viral Tracks. The album reached No. 6 on the Billboard 200. He nabbed a deal with major label Columbia Records (Beyoncé Bod Dylan, Adele), appeared on late night talk shows, performed at South by Southwest, read stories about himself in The New York Times, Rolling Stone, and many other major publications, and listened to “Coming Home” featured in an Apple iPhone commercial.

A few weeks ago, Bridges serenaded Willie Nelson at the Gershwin Prize Tribute Concert in Washington, D.C., and then sang with Macklemore & Ryan Lewis at the televised American Music Awards hosted by Lopez.

This Saturday, he’s the musical guest on Saturday Night Live hosted by Ryan Gosling. (Watching parties are planned all over town, including at Shipping & Receiving.)

Bridges’ suave style of writing and singing came alive with the Niles City gang. A new generation of music lovers is digging the sounds of vinyl and reel-to-reel tapes. The trend began some years back as music purists longed for the warmth heard on vinyl records, as opposed to the crystalline clarity of digital. Niles City wants to give musicians the opportunity to capture that warmth and experience a recording experience that harks back to the old days.

Jenkins, Block, and Vivion sought out a highly experienced studio designer with ties stretching back to the early days of rock ’n’ roll. Suffolk spent most of his life in England working in studios before starting a design business in Dallas about 25 years ago.

“We needed someone with tons of experience,” Vivion says. Suffolk has “done work for one of my friends who has a studio in Dallas. We needed to clarify the direction we were headed, and [Suffolk] came in and saw the space we were going to work with and put a plan together.”

The Niles City crew tweaked Suffolk’s ideas here and there, and together they developed a vision that combined the old and new. For instance, sliding sound buffers attached to the walls are made of new flame-resistant material designed to replicate the old burlap bags once used.

“In the old days, they would use burlap, which was never fire-rated, and it was dusty and it stank,” Suffolk says. “Most studios used to stink pretty bad.”

Many nods to the past are incorporated into Suffolk’s design, such as a large, round clock. Modern studios tend to shun timepieces. But Suffolk wanted one in a prominent place on the wall. Most of his architectural decisions are made to produce the best sound, but some designs are purely for aesthetics. Recording relies on ambience as well as performance, mic placement, mixing, and other aspects, he says.

“I started building studios in 1982,” he says. “The guys wanted a studio with a sound that you could get from vintage rooms instead of the new over-acoustic rooms that studios build to work with digital.”

Suffolk played organ with the Fabulous Poodles in the early 1970s and had a couple of hit songs before deciding he’d rather work in studios than on the road. He worked as a tape operator at numerous British studios, including Pye Records, where The Kinks recorded.

“The Kinks would go in there in the days when you could block-book a studio for six, seven weeks,” he says. “They would have a rough number, sit around and record. I’d be putting mics up. They’d listen to how it was going, lay it down on tape, listen again, go put it down differently.”

Once the musicians liked the sound, they’d record the song straight through live. Sometimes a harmony or guitar line would be added later, but most of the songs were one-offs. That style of recording relies on bands being able to play songs all the way through without messing up. Many bands today piece together songs, a style that relies on digital gadgetry rather than a live performance.

Suffolk and Niles City have nothing against digital equipment. They’ve all used it on other projects in other studios. But digital has gone “from the sublime to the ridiculous,” Suffolk says.

He likes to hear the whirring of a tape being rewound, a sound that always excited musicians eager to hear what they’d just recorded. He likes the smell of wires and hot tubes. And he likes the look of a lived-in room, one that’s had a thousand guitars leaned up against the wall and a thousand amps rolled across the floor.

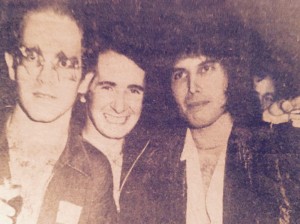

One of Suffolk’s first jobs was to remodel England’s famous Trident Studios in 1982. Rock royalty such as the Rolling Stones, David Bowie, Elton John, and Queen had recorded there in the 1960s and ’70s. The Beatles recorded “Hey Jude” there, among other songs.

Suffolk’s favorite studio is Abbey Road, a mountainous building with plenty of room to enjoy the benefits of aural spaces and natural reverbs.

“People record and go, ‘How can I get that sound?’ They can’t get it out of little, boxy studios,” Suffolk says.

After leaving the Poodles, Suffolk began eschewing photographs. He doesn’t want his picture floating around online, although he’s a perfectly normal looking person. He prefers his studios to represent him. That’s why he’s covering his face with a clock in our photo and hiding behind Elton John and Freddie Mercury in the vintage photo.

“I’m not interested in fame,” he says. “I just like the work to stand by itself and for me to feel personally satisfied.”

Suffolk wasn’t involved in the first recording with Bridges, but he couldn’t wait to get involved after meeting the Niles City Sound crew in February. Suffolk is a fine musician who’s played on many recording sessions over the years, but he feels his best contribution to music is through creating studios with a distinctive voice and warmth that make an entire album sound better.

His designs are not only controlled by available space and budget but also by outside influences. How close is the studio to a train track? Is it in a flight path? Is a pressing plant next door? Perhaps most importantly, how passionate are the owners?

“I go to a lot of studios,” he says. “I came here, and within the first five minutes, I could feel the energy and excitement. I was so excited about the sound and what they were doing. You could feel the honesty in the air and the enthusiasm, which I hadn’t felt in a long time in studios because they’re becoming so bland. Everybody wants to do it because they want to be famous or a pop star. These guys did it for the love of music and saw someone who was ultra-talented and the songs were great. That’s the thrill.”

The high level of musical talent in Texas, particularly in North Texas, is what drew him here from his native country 25 years ago, he says.

“I love working with musicians,” he said. “I understand musicians. Some of the studio designers in the world don’t understand musicians. I pride myself on running the whole of the gauntlet in the music business. You have to apply your craft to their craft. They’re going to see a beautiful looking studio. It’s not going to look like a Starbucks. I try to create a sound first and a look afterward.”

But there’s one important thing he can’t build from scratch: a hit record hanging on the wall. Suffolk knows a guy who spent $6 million building a Nashville studio 10 years ago and still hasn’t produced a hit song.

Niles City Sound has its hit in “Coming Home.” Bridges, Jenkins, and Block will be touring on the strength of that song for months to come. But at some point, Bridges will have to come up with the oft-tricky second album. “Sophomore curse” describes the difficulty in replicating the success of a breakout debut album, especially one so trapped in a long buried past. Artists tend to use their best songs for their first album and sometimes struggle to come up with an equal or better batch of songs.

Jenkins doesn’t expect the prolific Bridges to experience such a problem.

“He is constantly writing music,” Jenkins says. “He’s got some stuff to say, and he has a unique way of saying it.”

In addition to the first album’s 10 songs, Bridges has written and recorded “So Long” for Concussion. The new Will Smith movie was released on the day Jenkins and I spoke for this story.

“Right now, with the inclusion of this track that came out today, the world has only heard 11 songs from Leon Bridges,” he says. “When he’s ready to record, he’ll have far more than one LP’s worth of material, so he’ll have a lot to pick and choose from.”

All indications point to that album being recorded at Niles City Sound, although not even a handshake agreement exists. Jenkins, Block, and Vivion hope Bridges records there and feel they are creating a studio worthy of the honor.

“I’d say the chances are good, but you don’t know,” Vivion says. “He’s got a lot of work to do to support this record. A lot of time will go by between now and the actual time it will be to record the next record. I’d love it if he came back.”

Bridges, who was visiting New Orleans for Thanksgiving before heading to New York City to tape his SNL spot, could not be reached for comment.

The casual business relationship speaks to the easy manner in which these guys operate.

“We just kind of let things be what they are,” Vivion says.

Bridges is a Columbia artist now, and the company might have other ideas. Then again, the label has been friendly and cooperative throughout its involvement with Bridges and the Niles City boys.

“Columbia has been amazing,” Vivion says. “You hear horror stories about the way things go for various artists, but these people have been nothing but supportive. They let us run with what we were doing.”

What they’re doing is unique if only because it’s a return to the way of doing something long ago, back before CDs and iTunes. The room is a combination of art and science grounded by American-made equipment from music’s glory days, including two 1960s-era Ampex reel-to-reel tape machines that were used for recording Grateful Dead live performances, a Collins radio broadcast console from the mid-1940s to amplify microphone signals, and an Auditronics 501 console from the famous Wally Heider Studios in San Francisco, where rock greats such as Van Morrison, Jefferson Airplane, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Gram Parsons, Link Wray, and many others recorded.

“Back when that gear was made, it wasn’t made to see how much profit margin can we milk out of this piece of gear, and it will be a disposable commodity in a year when something different comes out,” Vivion says. “It was made to last. It’s a pain, honestly, to work with that equipment because it does break down. Some of that equipment is going on 70 years old. Occasionally you have to chase down a problem. I’m not in love with that, but that’s the best sound we can possibly achieve at the moment.”