It seems to me that local musicians and music stores are really the best parties to turn to in the wake of gear theft. Carpenter told me that the police didn’t investigate his case at all.

“They didn’t watch any of the security footage, and, in fact, they didn’t even request it from my apartment complex. And when the perps were caught trying to sell the stolen goods, the police didn’t even search their car for more of what was taken.”

Of course, he was already doing his own detective work, contacting every used music store in Fort Worth within two hours of filing the police report, as well as making the rounds of pawn shops.

“Within 24 hours, I had visited every pawn shop in Fort Worth with my list, but I couldn’t even get the [Fort Worth] detective assigned to my case to return my phone calls.”

As it happens, I couldn’t get ahold of a detective, either. Scott White had positive things to say about the cop assigned to his case, but he didn’t return my calls. And Choat said that if you do as much of the detective work as possible, the police will be more than happy to show up ASAP.

“If you give them enough information, they can help out a little,” he said. “They’ll definitely show up to make an arrest.”

And to the police’s credit, at least in White’s case, they were actively looking for his guitars.

But most of the time, the police can’t do much about stolen music gear beyond taking the reports, and even with the help of social media and the network of musicians who are passionate about fighting gear theft, the crimes often go unsolved.

******

The most tragic local gear theft in my memory occurred around 2007, when the rehearsal space of Haltom City fuzz-rockers The Me-Thinks and their friends was burglarized.

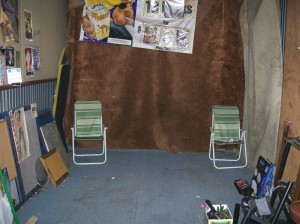

Me-Thinks frontman and bassist Ray Liberio said the space faced the street, so “pretty much anyone driving by could see what we had in there. There was always someone rolling by and going, ‘Y’all in a band?’ For the most part, though, it was pretty cool out there. We had the barbed wire fence that you had to have a key code to get in.”

The fence eventually broke, however.

“I’m pretty sure that if that fence hadn’t been broken, we wouldn’t have had to worry about it,” Liberio said. “But the landlord was pissed at the city, wanting to charge him all these taxes on the land, and I think he had enough of the bullshit, so he quit fixing things, and anyone could go in and out of that complex through the broken gate.

“We were up there almost every night,” Liberio continued, “and I think anyone who would’ve been interested would’ve been able to figure out our patterns, because we were never there during the day. I don’t know how they did it, whether they rolled up with a truck or made a bunch of trips, but they took everything, even the porno pictures off the wall and broken speaker cabinets we were using to hold up other speaker cabinets. Those fuckers actually took our first Fort Worth Weekly Music Award.

“It was a devastating blow, pulling up to the warehouse and seeing the roll-top door cracked open about a foot. And me and [Me-Thinks guitarist] Marlin were like, ‘Well, shit. No one else is here right now,’ and we opened it up, and the space was just empty, except for some pieces of trash. Talk about having the breath knocked out of you.”

The Me-Thinks had started collecting gear back in the 1980s, when the guys first got serious about playing. At the time, most musicians were upgrading to high-wattage solid-state amps and Jackson guitars, “more heavy metal-type gear,” Liberio said, which meant that goodies like a vintage Ampeg SVT rig and matching 8-by-10-foot cabinet could be had for a paltry $200. “We scooped up all the cool old shit we could find,” Liberio said.

In Liberio’s estimate, the theft was a little more than $40,000, based on resale values at the time.

“It was all vintage Marshall, Fender, and Ampeg gear,” he said. “The only things that didn’t really get stolen were guitars, because everyone took those with them at the end of the night. I lost two amps, a set of drums, all my cymbals. … Marlin had two or three amps up there, [Me-Thinks guitarist] Vince had four different amps. About 20 years of collecting shit. Just gone.”

Liberio and Marlin called the other guys and then the cops. Haltom City police came out, took statements, and a day or two later a detective called. Unfortunately, the victims weren’t really good at documenting serial numbers. There was even less the police could do.

“At first, they seemed like they were doing their job, contacting us over the first couple of days,” Liberio recalled, “but looking back, I feel like it was just for insurance purposes, because I thought, ‘Well, how do they even have the resources to track any of that stuff down?’ ”

One item did pop up, Liberio said.

“This guy bought our Fender Rhodes stage piano in a parking lot of a pawn shop on the West Side, and that guy immediately took it to Zoo, thinking he’d flip it. Tyrel Choat recognized it,” (the Rhodes logo was messed up and missing the “R”) “and we were able to provide photos that showed all the wear and tear.”

About five years later, another item popped up, a Marshall JCM-800 bass head and its matching speaker cabinet.

“They’re not rare, but you don’t see ’em every day,” Liberio said, “so when they show up in a Guitar Center, it’s something you remember.”

During a rehearsal, a friend who was hanging out commented on the sound of Liberio’s new bass rig (a different, bigger, louder Marshall) and mentioned that there was a JCM-800 half-stack at the Guitar Center on Hulen Street.

“I said, ‘Oh, man. I’d love to have another one of those,’ but I kinda put it out of my head for a few weeks. But one day I was in the neighborhood, and I popped in there and saw the matching speaker cabinet.

“It has this wheat-colored grill that has a really distinct stain on the front, like someone has taken a leak on it –– years of beers rattling off the top of it and splashing back up –– and then we had all our stuff stenciled with ‘Me-Thinks Haltom City,’ and I looked on the back of it, and someone had just taken a magic marker and just colored it out. I grabbed one of the guys and asked who I could talk to about this being stolen from me years ago, and then I called my friend Jay who worked at GC’s executive level. He told me to put a deposit on it first thing. It turned out that they had the [amplifier] head in the back, that they’d sold it, but there was a wait on it, too. So I looked, and, sure enough, it was mine.”

But because Liberio had already been paid out by his homeowners’ insurance, he wasn’t able to just take it back.

“Jay made me a good deal, though, sold it to me for exactly what they paid for it.”

He pointed across his kitchen to his den. “Now it’s sitting in there, and I played it last night.”

Like the police, homeowners’ insurance is not as helpful as you would like in these situations. Typically, it covers 10 percent of what’s in your house, pretty standard for up to $40,000. Liberio had a clause stating that 10 percent is covered in off-premise storage.

“The insurance tried to balk at it, asked if I used it to make money, which made me laugh pretty hard since I’m usually $30 in the hole at the end of a gig from my bar tab,” Liberio said. “Luckily, The Me-Thinks had never become an LLC, which would’ve messed up our individual claims. I think what I lost was about 16 grand, and they paid me almost $4,000, used to buy a new rig and help out some of the other guys who’d lost gear in the burglary as well, though the JCM-800 and Rhodes piano top were the only things that have ever surfaced.”

But sometimes, musicians are their own worst enemies when it comes to protecting their equipment. There have been plenty of times when I would wake up in the morning after a gig and bolt upright, realizing I’d left my bass in my vehicle overnight. And then I would resign myself to the fact that if it was gone, I deserved it for leaving it where it can be easily nabbed.

******