The last time I wrote up a show at the Amon Carter Museum, I wasn’t overly impressed and speculated that the lack of access to the museum during its remodeling might have been a factor. This might be a coincidence, but now that the museum’s remodeling is done and the parking lot is open again, the Carter has greeted the occasion with a spectacular exhibit. Like many of the works in the show, Self-Taught Genius: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum itself is messy and not always on point, but it is overflowing with creativity and imagination of a highly distinctive sort.

This would be worth going to just for the quilting on display. From a distance, an Amish quilt from the early 20th century appears to be made up of geometrical shapes of solid color, but look more closely and you’ll see plant forms in the stitching that give texture to the fabric. The same goes for the Whig Rose with Swag Border quilt made by Southern slaves, where floral shapes are stitched into the white negative space between the roses. The early American Hewson-Center Quilt features a realistically rendered vase overflowing with flowers in the center panel, while more abstract floral and geometric designs own the space around it. Carl Klewicke’s early 20th-century “Original Design Quilt” (made as a wedding gift to his daughter) is a much more sharply modernistic piece, with bright swatches of color shining luminously against a black background. Paula Nadelstern’s 1990s quilt, “Kaleidoscopic XVI: More Is More,” is inspired by Tibetan mandalas and shimmers in red and blue.

If quilting isn’t your thing, your eye will probably be caught by the large-scale pieces here, like the handsome, anonymously sculpted cherry-wood replica of the Empire State Building, standing almost eight feet high and held together without nails or glue. (Supposedly this was executed by a metalworker who worked on the construction of the real building.) Even bigger is Marino Auriti’s 11-foot-high model of the Encyclopedic Palace, a piece in wood, glass, and model kit parts by a Pennsylvania auto mechanic who dreamed of a giant complex that would house all human knowledge. As the exhibition label informs us, if the palace had actually been built, the central tower would be only slightly shorter than the Burj Khalifa. Marcus Illions’ flamboyant life-sized wood sculpture of a lion was created as a carousel animal, but prowling in the center of a gallery, it’s a rather terrifying sight, especially with its glass eyes staring you down. The Chicago hospital janitor Henry Darger has a 9-foot-long page from his illustrated saga of the childlike beings known as the Vivian Girls and their history of war, suffering, and triumph.

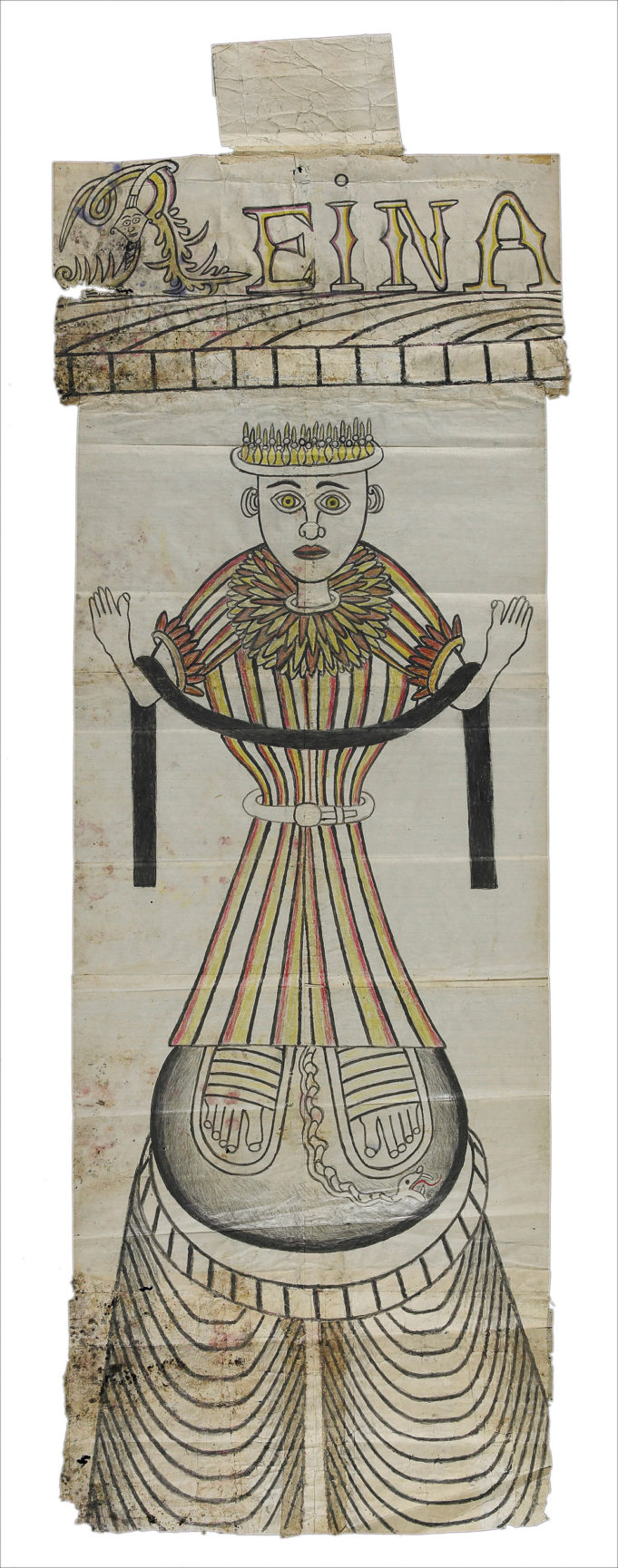

The Darger piece is just one of many that evoke worlds unto themselves. Some of the artists you feel might have earned a living as graphic novelists or video game designers at another time, like Eugene von Bruenchenhein with his hallucinatory oil painting on corrugated cardboard, “The Pile of Andrius.” Chelo González Amézcua’s “In the World” is a similarly psychedelic work drawn with a ballpoint pen, and Martín Ramírez’ “Reina” is a mixed-media rendering of a female figure distilled from Mexican religious iconography but with an uncanny power all its own. However, others display manic tendencies, like George Widener’s “Funeral for Titanic,” a huge 2007 drawing on paper napkins that’s inscribed with the date of every Tuesday since the ship’s sinking. (The artist is an Asperger’s syndrome sufferer, a former military intelligence analyst and homeless person, and he happens to share a name with one of the victims on the Titanic.)

For all the outsize personalities packed into this show, it would be a shame to let the smaller, less ambitious, more decorative works go unheeded. These include Solomon Grimm’s 1822 covered jar with a star decoration and Moses Eaton Jr.’s sample box with 10 panels, each painted in a different technique to demonstrate the painter’s mastery. Compellingly strange is David Cordier’s birth recorder for Hana Oberholtzer, an official document from 1816 that nevertheless includes floating heads painted into the border surrounding the text noting the baptism of this 11-year-old girl. Maybe most beguiling is Christian Strenge’s Liebesbrief, a circular love letter with watercolor hearts inscribed with love poetry. The world of outsider art is a seemingly endless one, and the works at the Amon Carter pay tribute to the varieties of human expression that our nation has seen over the centuries.

[box_info]Self-Taught Genius: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum

Thru Jan 3. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd, FW. Free. 817-738-1933.[/box_info]