Even though I couldn’t buy a job during journalism’s recession within the Great Recession, I did have one major career uptick. My book, I Love You Phillip Morris, was optioned and turned into a movie by the same name. It starred Jim Carrey and Ewan McGregor in the true story of Steven Russell, a conman and escape artist who broke out of Texas jails and prisons four times in five years, always on Friday the 13th and always in some nonviolent yet over-the-top way, such as dying his white prison uniform green and walking out the front gate posing as a doctor in scrubs. But Russell is always captured due to his Achilles’ heel: his love for his incarcerated boyfriend, Phillip Morris, for whom he always returns.

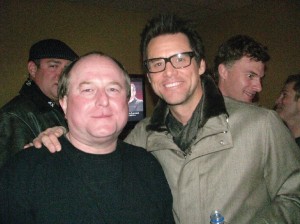

It’s a crime that neither Carrey nor McGregor was nominated for an Academy Award. Carrey also is a very sweet man who especially went out of his way to be nice to me. For example, while I was on the set for a cameo one day in New Orleans, he took me aside to tell me that I was going to beat my problems. And I had to laugh out loud when he was on the Late Show with David Letterman promoting the movie, and, of everyone involved with the film, I was the only person he mentioned by name.

But maybe the flight to Utah was a bad omen. On my way to see the movie at the Sundance Film Festival, I was struck with an almost crippling panic attack. I could feel blood flowing around and around in my head. I was sweating like a pig. I was sure I was having a heart attack. A flight attendant told me the pilot could divert the flight to Denver, but from the glares of the other passengers, I knew I would never make it there in one piece if I agreed. We proceeded to Salt Lake City, where I was rushed by an awaiting ambulance to an emergency room. There I was given a Xanax and told I was not going to die.

Not long after the movie premiered in December 2010, my doctors put me on a new leukemia medicine. Iclusig worked well. Extremely well. It was working so well that I was basically in remission. The problem was that my doctor was afraid that, like the other three leukemia meds I had previously been on, the Iclusig would also eventually stop working. If that happened, I would be out of pharmaceutical options –– and, for that matter, out of options entirely.

My doctor proposed a stem cell transplant. A transplant was possible at that point because of my state of remission. It was also possible due to the medical advances that had been made thanks to the life and death of David Vetter. The transplant would mean that I would be in semi-isolation for approximately 40 days, not an especially inviting option. However, if I didn’t have the procedure, and if the medicine later failed, I would no longer be in remission and a transplant would no longer be an option. And like I said, there would be no new drugs available. And I would likely die a painful death. Once again, I felt compelled to whistle.

When my oncologist –– Dr. Stefan Ciurea –– put it that way, I decided to take his advice and have the transplant. Plus, there was another little problem with the Iclusig. It was banned by the Food and Drug Administration. The only people who could continue to take the medicine had to be grandfathered in –– or not dead from a heart attack, a common side effect, apparently.

Not that the transplant option didn’t come with its own risks. In most transplants, Ciurea told me, the survival rate is only 50 percent at best. I got lucky, though. My odds improved to 80 percent after my doctor found two cell donors who were near 100-percent matches.

The other problem was the expense. Stem cell transplants cost in the range of $500,000. While it is doubtful I could ever pay all of it, I will have to pay some of it.

There also would be the cost of housing and living expenses post-hospitalization. I was told that, following the transplant, I would be confined to the hospital for a couple of months. After that, I would continue to receive treatment on an out-patient basis almost daily for another month.

Luckily, a friend stepped up and said I could stay at his house during my recovery. Armed with that information, I said yes to the transplant. First, I had to undergo some preparatory episodes of chemo and radiation that caused my hair to fall out and killed my immune system. A few weeks later, on April 11, 2014, I was anti-climatically hooked up to an IV bag of a fluid that looked like an Orange Crush. For the next 45 minutes, I sat back in my hospital bed and let gravity do the work. And that was that. No big surgery. No operating room. No sedation. Just me, one of the many excellent MD Anderson nurses, and an IV bag.

But instead of a couple months of recovery, I was not allowed outside the hospital for nearly 90 days. I thought I was losing my mind. In retrospect, I wish they had kept me even longer. Hell, I wish I was still there. The year since I was discharged has been nothing but one long nightmare. I had been told I would be able to return to work immediately. But there have been so many hospital visits and physical setbacks that only now do I feel well enough seek full-time employment.

******

After the stem cell transplant, I encountered major pushback over my plans to drive to my out-patient treatments from MD Anderson officials who were concerned that I would black out and have an accident. It seems as though I had an almost daily confrontation with someone from MD Anderson over the issue.

With oncologist appointments scheduled almost daily, it was impossible to leave the hospital –– unless hospital brass wanted me out. On a couple of occasions, I was kicked to the curb after being gang-banged by a half-dozen or so MD Anderson officials, even though I thought I should stay longer and receive additional treatment. Other times, these people fought me over the idea of leaving. During one episode, I convinced my doctor that I was OK to drive back to Cleburne. But once I got home, I soon developed a condition.

Graft vs. host disease is common among transplant patients and is really, truly scary. Basically, you lose your mind. I was unable to put gas in my car. I couldn’t answer simple questions. I was scared to death, and I felt like I was being kidnapped when the people with butterfly nets finally tracked me down and put me back in the hospital.

At the hospital in Cleburne, I was also treated for staph. My pic line, which allows for multiple IV hookups, had become infected. Pic lines are really popular at MD Anderson. It’s like having a sterile nail in your upper arm. I’m surprised people don’t die from it every day.

A couple more hospitalizations for transfusions followed, after my blood counts –– especially my platelets, white cells, and hemoglobin –– became dangerously low. My numbers fell so far because, prior to receiving an anonymous donor’s stem cells, my immune system had been killed off to facilitate reception of the new system.

But the highlight of last summer was when I got into an argument with my younger brother over some popsicle sticks. I had dropped them on the floor and failed to immediately pick them up and throw them in the garbage. After telling him to go commit an unnatural act on himself with the sticks, he left and then returned with a baseball bat. He hit me over the head, giving me a concussion and leaving a wound that required eight staples to close and several more days of hospitalization. I didn’t press charges –– probably because there had been a couple of incidents in which my meds had made me ill, and he cleaned up after me. He is also good to my dog.

I am no longer welcome at my family home –– although my mother and I talked on the phone this week for the first time in a couple of months.

Indeed, there are not many places where I am welcome these days. I have spent the last few months –– and most of my money –– in cheap motels and occasionally on a friend’s couch or in a spare room. I am always on the verge of running out of money and soft places to fall, and I appear headed for either a men’s shelter or the inside of my car. The thought scares me to death. I can’t even whistle.

I hope the Fort Worth Weekly pays quickly. I have to admit that after spending most of the last year in the hospital without working, my confidence in my ability to write coherent sentences was somewhat undercut. But having this story accepted, it sort of puts the bad boy glint back in my eyes. I even feel like saying I’m prepared to rise from the ashes like a freaking phoenix, taking names and kicking ass.

After all, I am certifiable. Or to quote Steve Earle again, “I feel alright / I feel alright tonight.”

“To paraphrase Steve Earle in his ode to the late, great Townes Van Zandt, what’s a poor Fort Worth boy to do?”

___________________

I think it’s incorrect to say that you are paraphrasing Steve Earle when Guy Clark wrote those words. (What’s a poor Fort Worth boy to do)

Sure, Steve Earle’s Fort Worth Blues does convey a similar sentiment about Townes Van Zandt, but not those exact words which are Clark’s.

Kharma is a bitch. You stole a guys story and let him rot in prison while you made money and didn’t him a dime. Buh buy Bitch! I don’t even think Steven Russell has seen the whole movie.