To paraphrase Steve Earle in his ode to the late, great Townes Van Zandt, what’s a poor Fort Worth boy to do?

It’s a muggy weekday morning, and I’m sitting on the low ledge of the muddy, cigarette butt-filled courtyard of a downtown Houston office building. My orange and white Chuck Taylor University of Texas Longhorn high-tops will be OK. The same may not be true for my own butt, which is wedged up against the black wrought-iron fence that serves as a barrier to the people who need help and the people who supposedly give it. Along with about two dozen other folks, I am waiting for the nondescript entrance doors to open and lead me to the world of the housing lords. We might as well be eager kids waiting for school to open, as it looks about the same –– with the exception of our advanced years.

Today, after two unsuccessful tries, I arrived especially early, staking my hopes on a spot near the door. Finally, after a 90-minute wait outside, I am allowed in and granted a five-minute audience with one of the processors. The first thing he asks for is my letter. And I promptly hand it to him, my official documentation certifying that I am homeless. Yes, I now possess proof positive that I have officially hit rock bottom. I couldn’t be prouder, I think to myself in mock humor, especially when the processor tells me to come back in two weeks. In addition to the all-furnished, all-bills-paid, city-owned units that may be available, the city, he says, may soon offer to pay a percentage of the rent –– 80 percent, maybe more –– of privately owned housing that applicants find on their own.

Things could be worse. At least that’s what I tell myself, continuing the joke inside my head. For example, I could have been left at the altar, or I could have been laid off from an investigative reporter job at the Houston Chronicle, where I was doing the best work of my career. Or I could have had back surgery, with the need for more. Or someone related to me could have hit me over the head with a baseball bat. Or I could have even been diagnosed with a rare form of cancer. I also might have had to resort to internet panhandling.

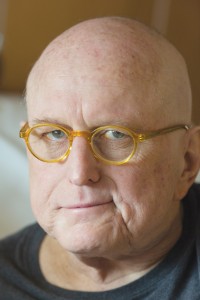

But –– oh, yeah –– that’s right. All of those things actually have happened to me over the past few years. But of all of the setbacks, scars, and embarrassments, the cancer, an unusual form of leukemia, in my case, maintains the strongest grip on my life –– although long-term unemployment gives the C-word a run for its money. And the two are inextricably intertwined. Efforts by my oncologists, whom I love dearly, to prolong my life have been successful. So far, that is. Unfortunately, for me, their success has also been my ruin. Constant trips to the hospital for transfusions or to deal with bouts of pneumonia have left me stymied and frustrated when it comes to looking for work, full-time or freelance. Obviously, this is no feel-good story about defeating cancer. Instead, it’s more of a close look at a slow-motion train wreck.

******

David Vetter died for my sins. At least I thought he had. Vetter was the original Bubble Boy. He was born in 1971, even though his parents and Texas Children’s Hospital knew he would not have an immune system. Just like his older brother, who had died shortly after birth a few months earlier. But this time the doctors would be ready. This time, the child would be born in a sterile delivery room and immediately rushed into a sterile so-called bubble where everything would also be sterilized. For his first few years, David resided first in that bubble and then in a larger one as he grew. David also would never feel human touch –– not until a last gasp effort to remove him from the bubble resulted in his death when he was 13 about a month later.

Although I obviously haven’t suffered like David, I had a pretty bad 2007. First, I was diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia. When I got the news, I had just returned to the Chronicle city room after attending the funeral of a dear friend who had died unexpectedly. Earlier that week, I had gone to my doctor for my yearly routine physical. Already numb, I was now being told I had leukemia. It all seemed so surreal.

CML is not the worst kind of leukemia, but my case was worsened by the so-called Philadelphia defect. To make a long story not quite as long, that meant that one of my chromosomes had a crack in it. Until the crack is healed, no matter how good my test results may be, I will always be at risk of remission.

A couple of months later, in anticipation of the Great Recession, I was laid off from the Chronicle, where my reporting and writing partner, Roma Khanna, and I had discovered how widespread bad science and malfeasance were within the Houston Police Department’s crime laboratory, especially in its DNA division. In response to our investigation, the City of Houston was forced to hire its own outside investigative team at a cost of more than $5 million and then later construct a new lab separate and apart from the rest of the police department. Until the axe came down, I was feeling pretty good about myself.

Around the same time, my marriage engagement also went south. For that, I take full responsibility. I am obviously a bad man and am now being punished for my wicked ways. The wedding had been planned for later that year in Marfa but was canceled about a month after my diagnosis, the one for leukemia and, I suppose, for being a bad man.

******

“To paraphrase Steve Earle in his ode to the late, great Townes Van Zandt, what’s a poor Fort Worth boy to do?”

___________________

I think it’s incorrect to say that you are paraphrasing Steve Earle when Guy Clark wrote those words. (What’s a poor Fort Worth boy to do)

Sure, Steve Earle’s Fort Worth Blues does convey a similar sentiment about Townes Van Zandt, but not those exact words which are Clark’s.

Kharma is a bitch. You stole a guys story and let him rot in prison while you made money and didn’t him a dime. Buh buy Bitch! I don’t even think Steven Russell has seen the whole movie.