Wayne Carson is already seeing improvements.

CEO of ACH Child and Family Services, a 100-year-old Fort Worth-based nonprofit that’s recently been hired by the state to oversee foster care in seven counties, including Tarrant, Carson is optimistic that the improvements will continue despite pointed questions about the overall program from a legislative review commission.

“ACH has 100 years of experience in this field,” he said. “Because this is a community-driven model that’s not state-based, we can be more effective, more efficient.”

Last year, Tarrant County led the state in confirmed cases of child abuse and neglect (6,092), according to the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. Tarrant County often ranks in the top three Texas counties with the highest rates of child abuse.

When a victim of child abuse cannot be placed with a parent or relative, Family and Protective Services works with a network of organizations to find a temporary foster home for him or her. While the numbers fluctuate from month to month, ACH oversaw an average of around 1,300 foster children last spring.

The redesign efforts began in 2007, when the Texas Senate authorized Family and Protective Services to restructure the foster care system based on recommendations from an internal report. The restructuring focused on privatizing the management of foster care groups and individuals under one agency. In the past, the network of foster homes and agencies would directly contract with Family and Protective Services.

But the plan also opened the child welfare program to management by private, for-profit businesses with little increase in state spending to fund the expansion. Last year, a for-profit company, Providence Service Corporation of Texas, abruptly pulled out of the new program after being tasked with overseeing the redesign effort for 1,100 foster children in West Texas. Providence was the first business awarded a contract under the redesign plan, and it failed. ACH was recently awarded the state’s second redesign contact.

Several factors, said Providence CEO Mike Fidgeon in The Texas Tribune, contributed to the decision to terminate the contract, including unanticipated transportation costs to care for children in the expansive, rural region.

And in the same article, Ashley Harris, director for the advocacy group Texans Care for Children, said the news “confirms it’s time to stop expanding privatization and start adequately funding child protection.”

In a 2014 report, a long list of problems in the foster care redesign efforts were highlighted by the Texas Sunset Advisory Commission, a group created to eliminate waste and inefficiency in government. Among the report’s list of concerns were the lack of “additional investment of state funding with the expectation that the quality of care provided to foster children will improve” and questions about the efficacy of privatization efforts. The report went on to list several states that have faced challenges when relying on for-profit companies.

Linda Garcia, ACH community relations director, is quick to point out that privatization describes any group, including a charity, that has replaced a government agency.

While the failure of Providence is a painful reminder of the difficulty of managing several counties, Carson said, “ACH brings a different perspective and experience to this issue [than Providence did]. ACH has long-standing relationships with the organizations and agencies involved in caring for and nurturing children in our communities. We know the community is counting on us to get this right.”

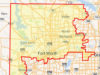

To effectively implement the changes and meet state guidelines, ACH was required to prove it was qualified to handle receiving and distributing state foster care funds for seven counties (Erath, Hood, Johnson, Palo Pinto, Parker, Tarrant, and Somervell).

“When we applied, we were celebrating our 100-year anniversary,” Carson said. “That was a huge selling point. Some of the competitors were out-of-state providers. It’s hard to have a community-based local approach to this if you aren’t from the community.”

The redesign brings several changes to how foster care is managed, Carson said. This includes a new approach to coordinating efforts among the dozens of foster care agencies in the seven counties. The top-down approach, he feels, allows for quicker placement of foster kids and a better understanding on which areas are experiencing the greatest shortages of foster homes.

ACH now oversees 44 independent foster care providers. Before the redesign, Carson said, most of them were not effectively communicating with one another.

“There were small agencies that really wanted to help but didn’t have a lot of capacity,” he said. “Under the redesign model, we took a more of a teamwork-centered approach to care.”

Managing the regional foster care system under one provider has made a range of tasks, including data and statistics retrieval, quicker and more efficient, Garcia said.

“We were able to speak to stakeholders and find ways to focus our efforts on locating foster parents in rural areas without having to go through seven or eight levels of state approval,” she said. “If we submit a request to Dr. Carson, he can approve it right there.”

Other changes seem like common sense but had not been a requirement until now. Before the redesign, it would not have been unusual for a Fort Worth child to be placed in a foster home in Austin. Or farther.

“You want to keep kids in their home community,” Carson said. “We had a teenage girl who was in Houston and constantly running away. The therapist asked what we can do to help. ‘I want to go home and see my friends,’ she said. ‘I want to be around people I know.’ That’s a reasonable request.”

In the past, he added, siblings were often broken up because a home with multiple openings was difficult to locate.

“The state didn’t always know where a foster home with three openings was,” he said. “They would send an e-mail out saying they have three children. Well, if I’m a foster home, I might say I’ve got one opening, and so they put kids in the first homes that became available.”

The new database that ACH has compiled is addressing that shortcoming. North Texas, and most of the state, consistently faces a shortage of volunteer foster parents, but the problem is particularly bad in rural areas, especially regions west of Fort Worth. Carson and his staff now have a comprehensive up-to-date map of foster home vacancies and can focus volunteers to speak at churches and other community gatherings to raise awareness of the shortage crisis.

One looming question is if the state will adequately fund the new program.

“The state chronically underpays, giving 80 percent [of our request], which is really frustrating,” Carson said. “We believe the state should be paying 100 percent.”

Garcia said the program got a small boost during the last legislative session. Lawmakers approved $1,200 one-time payments for each foster child.

“It’s the first program of its kind,” she said. “There’s a lot of political [caution]. It was 50 percent less than what we were seeking, but we were encouraged to see the support.”

Patrick Crimmins, media relations manager for Family and Protective Services, said a total of $6.9 million was appropriated by the state legislature this year to fund the foster care redesign program over the next two years. In 2014, Family and Protective Services doled out $399,426,761 to foster homes out of a total annual budget of $1.5 billion.

In addition to the $1,200 payments, the funds cover $1 million in “start-up costs” for contractors and $400,000 for two new Family and Protective Services positions to manage the redesign program.

There have been no changes in policy since the failure of Providence to fulfill its contracted portion of the redesign plan, Carson said, and his department makes no preference between for-profit and nonprofit businesses when awarding contracts.

With the data that ACH has collected in the six months since implementing the new system, Carson said his company has exceeded several state benchmarks, including the percentage of foster child siblings placed in the same home and foster children placed in foster care within 50 miles of their previous home.

The biggest shift Carson has seen in public perception has been away from thinking county to county and realizing that the region is one community that can benefit by pooling its resources.

“We need to stop thinking about Palo Pinto foster kids and Tarrant County foster kids,” he said. “These are all our kids.”