Sunday morning, last day in May. The sun had finally beaten back the clouds after weeks of rains, and the city was crisp. The air was clear. Edges of buildings stood out in sharp relief without the usual veil of smog. The rails behind the old Texas & Pacific Warehouse on Lancaster Avenue, normally a hive of activity, were unexpectedly silent.

The giant railroad cars were locked in place. Nothing moved through Tower 55, the largest railroad intersection west of the Mississippi, which has 125 freights roll through on a typical day. The rains had evidently slowed the pace of rail through whole swaths of Texas. The quiet was eerie.

And then a bell rang. A simple clank-clank-clank, and slowly a faded yellow and gray Union Pacific engine pulled into view from behind a row of trees hiding the rails. Behind it a Kansas City Southern engine, brand new and gleaming in black and red, helped pull a string of mixed cars that had just been put together at the Union Pacific’s Davidson rail yard, several miles to the west. The train pulled to a stop behind the monumental U.S. Post Office building, next to the warehouse, in line for the Union Pacific computers to give it the go ahead to leave the yard.

The trains moving in and out of Fort Worth weren’t always run by computers, but they were always vital to Cowtown. When the first rails arrived in 1876, they helped turn Fort Worth into a real city rather than a town known as the last major stop for cattle drivers to rest and re-up their supplies before heading onto Oklahoma and Kansas on the Chisholm Trail. When those lines expanded farther west, the great cattle drives were done, but the cattle still wound up in Cowtown before moving on, much of it as processed meat once the Armour and Swift plants opened just after 1900. But those trains didn’t just move meat: With one of the few north/south and east/west rail exchanges in the western United States at Tower 55, Fort Worth became the dominant interchange for all rail goods west of the Mississippi. It was the stuff of legend.

The number of passengers and volume of goods passing through Fort Worth became so large that in the late 1920s, the Texas & Pacific Railroad, which later became the Union Pacific Railroad, hired noted architect Wyatt C. Hedrick to design a passenger station and also a warehouse on Lancaster, abutting the Lancaster rail yard. But these were no ordinary buildings. For the passengers, Hedrick designed a 12-story Art Deco masterpiece completed in 1931. The lobby of the Texas & Pacific Railway Passenger Terminal featured glass, brass, plaster, marble, and a gorgeous ceiling from which hung golden chandeliers. Farther down Lancaster, the Texas & Pacific Warehouse was designed as a sprawling 580,000-square-foot, eight-story slightly subdued Art Deco building used for the storage and distribution of merchandise that came into Fort Worth from all over the country.

Between those buildings is another Hedrick masterpiece, the post office building, a Beaux Arts beauty from 1933.

Unfortunately, not long after the buildings were completed, passenger service began to decline. When it stopped altogether in 1967, the passenger terminal fell into disrepair. In the 1970s, the warehouse shut down, and except for a stint as the world’s largest paintball arena and a Halloween attraction during the 1990s, that building has been vacant ever since. But in 1978, both buildings, along with the post office building, which is now empty, were named to the National Register of Historic Places. The passenger terminal has since been restored to its former opulence on the ground floor and on the other floors turned into private residences. The warehouse has not fared so well. There is hope that it will, like its sister building, the passenger terminal, be restored and turned into apartments or condominiums.

A similar fate met with the physical building at Tower 55. With the Union Pacific running the Fort Worth yards via computer from the company’s headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska, Tower 55 is just a small dark building in the shadow of the intersection of 35W and I-30, a historical landmark but not much more.

******

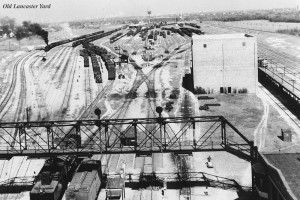

But while the beautiful T&P buildings may no longer be in service and Tower 55 home to just a couple of UP offices, the rail yards have continued to grow. At the west end sits the Davidson Yard, a sprawling 385-acre complex with 43 tracks on which to build and break down commercial freight trains — what the railroad men call “classifying” — and an additional five tracks to allow freights that are just passing through.

“We classify 21 trains a day here,” said Blake Woodson, Davidson’s burly, bearded manager of terminal operations. “We’re really building those trains here. It’s all we work with at Davidson. If you’ve got a train with 93 coal cars or anything else that doesn’t need to be broken down, you just use one of the tracks that bypass what we call The Bowl and head straight on to Tower 55.”

The Bowl, he explained, are the 43 tracks in the center of Davidson where the breaking down and building up occur. And there’s a real art to building a train, he said.

“You never put the weight at the rear of the train. You want that up front. And you wouldn’t put a car full of lumber next to a car full of sand, either, because that would put too much weight on the track. So you separate those out. Oh, and if you’ve got 50 empty cars and 50 full ones, you don’t put the empties up front.”

“Why not?”

“Because those full cars are going to take a little longer to stop than those empties, and you don’t want those empty cars getting bumped every time the train slows down.”

Woodson talked with enthusiasm about trains and the yard.

“I was born to do this. I’ve been at it 19 years, and I could keep doing it every day for the rest of my life. I love it.”

Woodson comes from a long line of railmen. On his mother’s side are two generations of men who worked the railroad. On his father’s side, he’s the fourth generation.

“My great-grandfather, my grandfather, my father, and now me, along with some uncles and such, all worked trains,” he said. “Walter Rice, my great-grandfather, was a conductor for the Union Pacific out of Kansas City, and my grandfather was an engineer for UP, also out of Kansas City. My dad was a train dispatcher and corridor manager. They’re the guys who make certain that dispatchers have a good plan for getting trains to where they’re going, making sure you have crews ready for crew changes, making sure you’ve got a new engine available if you need one.”

Woodson started out as a crew dispatcher in Denver. “In the old days, before my time, there were probably five men who made up a crew,” he said. “These days, we just use two: a conductor and an engineer. They can work no more than 12 hours before there’s a crew change. The first crew heads to a hotel for the night and picks up a new train coming home the next day. They run the same routes as a rule, and your job as a dispatcher is to make sure your crews are ready. If you’re running more eastbound trains than westbound, for instance, you might need to put an extra crew or two into a van to get them where they’re going.”

I asked him who runs the train? Engineer runs the train, he said. Conductor gets the paperwork and sees to the safety of the train, though most of them can do each other’s job in a pinch.

“Who’s the boss?”

He laughed.

“Both of those guys consider themselves the top dog,” he said. “The engineers all say it’s their train to run, but the conductor always says it’s his train and the engineer just runs it. But if you needed to stop that train for any reason, both of them have emergency stopping powers.”

Woodson explained that on every freight these days a crew-alerter beeps every 90 seconds, “and you need to acknowledge that by pressing a button on the dashboard, or the train will stop. If you’re not alert enough to hit that button, that train is going to stop pretty quickly, maybe 15, 20 seconds.”

Woodson worked up from a crew dispatcher to a train dispatcher at the Union Pacific headquarters in Omaha for five years. He became a corridor manager for a year and then came to Fort Worth as the manager of yard operations.

“I finally got bumped up to manager of terminal operations, and I’ve been doing that for 10 years now.”

“Did you ever want to be an engineer? Y’know, drive the train?”

“No,” he said. “That would be interesting for about three days. Doing what I do presents new challenges every day, several times a day. I like that.”

******

Nice job, Peter, and you too Madeleina on the photo.