Texas Music icon Robert Earl Keen Jr. has made almost 20 albums in his career, but none like his latest. He shares his love of bluegrass on Happy Prisoner, a tribute album of mostly traditional tunes. A friend of mine is a big fan of Keen’s, but when she heard about the new album, she said, “Yuck. Bluegrass. I can listen to that for about six minutes.”

I’m not a huge fan of bluegrass either. But a funny thing happened on my way to the trash bin –– I listened to Keen’s album and it kicks ass. His grizzled voice doesn’t lend itself to the high lonesome sound favored by bluegrass purists, and Keen is smart enough to refrain from splitting his pants trying to mimic Bill Monroe. Instead Keen sings like himself. Since many of his original songs contain elements of bluegrass – lyrics often marked by sorrow but set to happy music –– this album resembles a typical Keen project. And it’s obviously a labor of love. Keen sings with passion and conviction, and he used talented pickers and guest vocalists to help out, including Natalie Maines and Peter Rowan. And obviously the songs are memorable or they wouldn’t be standards.

Keen spoke with Fort Worth Weekly to fill us in on his new album, promote his June 5 gig at Billy Bob’s Texas, and answer any questions. He didn’t realize I’d solicited questions from Facebook friends and had a bunch. Keen’s a good sport. I’ve interviewed him several times over the years and he’s one of my favorite musicians to talk to (Ray Wylie Hubbard is another). Both speak freely without editing their thoughts much, they’re creative thinkers, and they make me laugh. That’s about all it takes to win my journalistic devotion.

“How did you come up with the Happy Prisoner title?” I asked. “I didn’t see a song on there by that name.”

“That came from a set of pajamas that my family, my wife and kids and I all put on during the holidays,” Keen said. “They’re horizontally striped goofy looking pajamas. We call them our happy prisoner pajamas.”

Keen was thinking about possible titles for the bluegrass project one day when he saw his pajamas. The garment reflected the bluegrass mindset perfectly, he said.

“The music is upbeat,” he said. “Most of the time the lyric is tragic. There is a dichotomy. I wanted to reflect that.”

Happy Prisoner was released on Dualtone Records in February after Keen spent more than a year working on it. Many of his early songs, particularly those on his first couple of albums, sound bluegrassy. In “The Bluegrass Widow” he even sang about being kicked out of a bluegrass band called the Front Porch Boys because he didn’t have the tenor voice so common in bluegrass.

“There were a lot of incarnations to the Front Porch Boys,” he said. “That was toward the end of it all. That band lasted about five years –– my entire college career.”

Was it true that the band kicked him out?

Sure, he said, so to speak.

“What I love about telling a story is, sometimes you fictionalize or dramatize it to make it a better story, but it’s all true,” he said.

His first album No Kinda Dancer (1984) incorporates many elements of bluegrass, in part because it was produced by Dan Huckabee, a Fort Worth native, former national dobro champion, and accomplished bluegrass picker. Also, Keen learned to play guitar by backing up a contest fiddler named Ronnie West, who played a lot of bluegrass breakdowns.

“It was a great learning experience,” Keen said. “You learn how to play these chords and then you do them over and over and provide the rhythm and sound, just playing backup for a guy playing fiddle.”

We talked about Billy Bob’s Texas, the “world’s largest honkytonk” where Keen has played about 50 shows over his career. The venue and crowd don’t typically lend themselves to quiet “fragile” songs that he can pull off at Bass Hall with ease, but Billy Bob’s is a great place to get wound up and turn on a crowd, he said. I asked if he’d ever met the club’s namesake, Billy Bob Barnett, who managed George Jones’ career for a brief period during the country singer’s hard-drinking days. Keen hadn’t met Barnett or Jones but shared a recollection.

“I went to Austin City Limits one time in the thick of the No-Show Jones thing,” he said.

The show’s producer came out on stage in front of the crowd and told them he wanted them to listen to something. Then he played a phone messag. The crowd heard Jones’ cracking voice saying, “I hate to tell you this but I’m not going to make your Austin City Limit taping.”

I told Keen a friend of mine had a three-legged dog he’d found on the side of road in a trash bag as a puppy. He named it Robert Earl and created a Facebook page for the mutt. Keen wasn’t aware of the homage he’d been paid but seemed impressed.

“That’s hilarious, I’ll have to check that out,” Keen said. “That reminds me of the three-legged dog that came to town and said, I’m looking for the man who shot my paw.”

I asked whether Keen had any other stories about people naming things after him.

“That’s as good as it gets right there,” he said.

For some reason the three-legged dog story made me think of a woman’s breast. “My first time backstage at a concert was at a Willie show in the 1970s and I watched him trying to sign a woman’s breast with a ballpoint pen. It looked kind of tricky, like there’s an art to boob signing. How often are you asked to sign boobs and what are the logistical challenges?”

Keen laughed and then uncharacteristically stammered a bit before responding (like any good married man with two young daughters should).

“I…almost every night…or every other night…I learn that what you resist persists in that world,” he said. “Sometimes it’s not the appropriate thing, and it’s particularly not as sexy as one might think. I just open up my sharpie and sign right across that chest. A ballpoint pen, I can’t imagine.”

The Houston native and member of the Texas Heritage Songwriters Hall of Fame had been talking for about 40 minutes even though his manager had only allotted 15 minutes for our interview. Keen has proven during previous interviews that he’ll talk much longer if he’s enjoying himself. He seemed to be.

“My friend Jim said he’s always been curious about the long introductions before songs that you do on the live recordings, and he wants to know if you write those verbatim or do a general outline and then ad-lib,” I said.

“Most of it is ad-libbing,” he said. “For some reason, one of the wonderful things I get from stepping on stage is my brain works better than normally. I just start talking and if it works I take the basics of that story and then repeat it and ad lib from there.”

He said bandmate Bryan Duckworth compares Keen’s stage banter to watching someone crawl out to the very end of a long branch on an apple tree. “Sometimes he gets an apple, sometimes he gets a seed,” Keen paraphrased him.

“My next question is actually a shameless plug disguised as a question,” I said. “Eric Knudson, who is involved in a tequila company with the comic Ron White, wants to know if you’ve tried Number Juan Tequila.”

“I have not tried it because I’ve been busy drinking my own Robert Earl Keen Beer,” he said.

We laughed at how effortlessly Keen had out-shamelessly plugged Knudson at his own game.

“Gayle wants to know if there could be any better training for being a Texas Music artist than being on that front porch in College Station that you and Lyle wrote about?” I said.

“There is no substitute for that training,” Keen said, describing the infamous house with the now-sacred porch as a sharecropper shack that had been moved into town. Old and rustic, it was soaked in history and mojo.

“The walls were one sheet of sheet rock, really thin and funky,” he said. “You really felt like you were rooted in the history of Texas in that house. Even as a young man I felt that way.”

Keen and Lovett, his college buddy, played many hours on that porch along with a lot of other young pickers.

“Nobody was trying to figure out how to be a star, we were just playing music and enjoying life,” Keen said.

“Gayle got greedy because she also wants to know whether you have a favorite line from your lyrics,” I said. “Her favorite line is ‘make me a bourbon sammich, mamacita.’”

Keen, at first, couldn’t think of one.

“They just bounce around in my head,” he said. “I can’t say there is a favorite line.”

He grew quiet.

“To swing away from humor for a minute, I wrote one called “The Wild Ones” that’s on the What I Really Mean album [from 2005],” he said. “There’s a line that I like that nobody ever brings up – ‘Love is like a songbird and every song she sings you hear a sweet reminder of her wings.’ That’s the line I’m very proud of.”

“Gayle will like that because she is a poet,” I said.

“Oh, that’s good.”

(Note: A YouTube version of the song is shown below. The line is at about the 2:15 mark.)

“Kevin Short says, ‘Ask him if he misses the small club days. I certainly do.’ ”

“I still play small club things,” Keen said. “There is a certain performing style when you play to people real close up. I hope Kevin can see one of those shows once in a while. I still play them. I was in Key West recently and did seven shows in five days by myself.”

“Darrell Byers wants to know why your mother doesn’t like you to play ‘Christabel,’” I said.

“My mom was a happy person and she always saw the glass half full, and I’d say she thought that song was too creepy,” Keen said.

I mentioned a poem I’d read called “Christabel” but I couldn’t remember the poet’s name and didn’t realize Keen’s song was inspired by it. Keen has read many of the English romantic poets such as Shelley, Keats, and Byron.

“I wrote this song sort of based on the Samuel Taylor Coleridge poem,” he said. “He was one of the more fantastic rock stars. You have to think of those poets as rock stars, and they did rock star stuff back then. Coleridge was like the Jim Morrison of the bunch. You could not contain the guy.”

Keen said Coleridge never finished his poem “Christabel.”

“I was thinking that this character is still floating around in the world and that’s how she lands back on earth,” he said of his song.

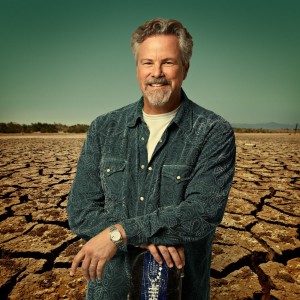

On my Facebook post that solicited questions, I included a photo of the singer standing on a dry lake bed and wearing a blue shirt with some fancy paisley patterns on it. “Pam Duke wants to know where you got that cool shirt,” I said. “Normally I would never ask such a silly question except that I, too, dig that shirt and would like to know where you got it.”

“That shirt, uh, I probably got it in a men’s store,” he said. “I go to men’s stores on the road…between sound check and the show. Most likely I bought that at a men’s store in Fayetteville, Ark.”

“John Cleveland is a young singer songwriter who wants to know where you start when you write a song,” I said. “Catchphrase? Melody? Opening line? Guitar work? Theme?”

“I like setting,” Keen said. “My songs sort of bear this out. I will sit and strum a guitar and think of a setting, where it is. It’s in a white building on a small side street and there are people there. What are they doing? Almost magically a form or a sentence takes shape and from there I start adding on. I’m not really good with emotional songs that much. Eighty percent of the world’s songs are emotional outpourings. Mine aren’t that way. I don’t know how to express them as well as others do. I’m always amazed at how beautiful [other people’s love songs] are. But ‘I love you ‘til I die’ doesn’t work for me. I can’t feel it. I like drama, narrative, color. I try to build something. I like to have a framework. And there is no substitute for the journalist’s ‘what, when, where, why, who, how.’ Fill in all those questions and you got a song.”

Great article Jeffro, sadly Robert Earl’s (the three legged dog’s)Facebook page is gone. Pecking out status updates with his one paw got to be too much for him. Mr. Keen’s always been one off my favorites, and I enjoyed the interview very much.

Bummer. Oh well, the facebook page may be gone but Robert Earl is still alive and kicking as well as a three legged dog can kick.

Jeff, you are such a brilliant writer. I love, love, love your writing

Great article, Jeff!

What a good read! Thanks, Jeff.

Not true Robert. “I’ll love you til I die,” may not work for you, but “I’ll love you til the end” and “til they lay me in the ground” sure made an impression on me. Loves a word I never throw around.