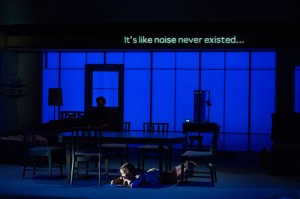

The stage of W.E. Scott Theatre looked like your typical Middle-American home: nondescript dinner table, disheveled living room, a bedroom. But a closer look revealed that right outside the house was a 20-foot stack of full garbage bags.

Dog Days is not your typical opera. Performed last Sunday as part of Fort Worth Opera’s 2015 festival, Dog Daysis scary and unsettling and very non-opera-like, which is precisely why FWO general director Darren Woods wanted to put it on in Fort Worth. Several years ago, he made a commitment to contemporary opera, and so in addition to Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata and Ambroise Thomas’ 19th-century interpretation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Dog Days are here.

Written in 2008 by David T. Little to a libretto by Royce Vavrek, the opera revolves around a dog. Or a man. Er, a man-dog, who comes sniffing around the house one day. “Get my rifle!” sang/shouted James Bobick in his thunderous baritone. Two and a half hours later, the father’s first line turned out to be the show’s concluding verse. The remaining family members came to life through their words and actions in relation to the creature (John Kelly). Brothers Elliott (tenor Michael Marcotte) and Pat (tenor Peter Tantsits) snickered and snarled, egging on their father with profanity, as the mother (soprano Marnie Breckenridge) seemed nonplussed, singing sweetly, liltingly, “Good dog.” The youngest child, Lisa (soprano Lauren Worsham), was transfixed, unable to take her eyes off the pitiable thing.

She gets close to him in Scene 2 of the opening act, approaching him as he’s curled up in a ball just outside the home. Worsham’s short, slender frame and high-pitched, sometimes nasally tone matched her character’s prepubescent qualities. The music swirled in dizzying layers to complement Worsham’s often chromatic lines of “We could be friends” and “You’re not normal.” Bell-like xylophones added a childlike fantasy feel to the eeriness as Lisa and the man-dog became friends.

A movie screen covered the stage above the actors. At first it showed a postapocalyptic grayish-purple landscape. Toward the end of Act 1, it offered a bird’s-eye view of the stage, giving the perspective of a helicopter overhead and highlighting the family’s isolation. Subsequent scenes were largely focused on each family member’s inner turmoil: the father’s inability to find food, the brothers’ preoccupation with smoking pot and looking at porno mags, the mother’s failing health, and Lisa’s feeble attempts to write letters to probably dead friends.