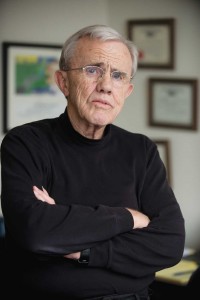

In the early 1980s, Dallas civil rights attorney Mike Daniel and his law partner Betsy Julian were fighting to desegregate public housing in East Texas.

At The Dallas Morning News, two reporters read the horror stories about public housing conditions from the law firm’s files and decided to do a national investigation. More than a year later, they reported that, just as in East Texas, public housing for poor families around the country was overwhelmingly located in crime-ridden, poverty-stricken neighborhoods, while federally assisted housing for the elderly — occupied largely by whites — provided significantly better housing, located in safer, cleaner middle-class neighborhoods. That project, called “Separate But Unequal,” won the News its first Pulitzer Prize.

A federal judge ordered East Texas officials to desegregate and equalize conditions in 36 counties, the most far-reaching desegregation order ever issued.

Another suit filed by Daniel and Julian against Dallas officials resulted in a settlement that allowed thousands of poor minority families to move into good housing in safe neighborhoods. Similar lawsuits in other cities helped improve conditions, forced governments to shut down high-rise horrors like the Cabrini Green project in Chicago, and gave the people who were living in those places a better chance at a decent life and choices in where to live.

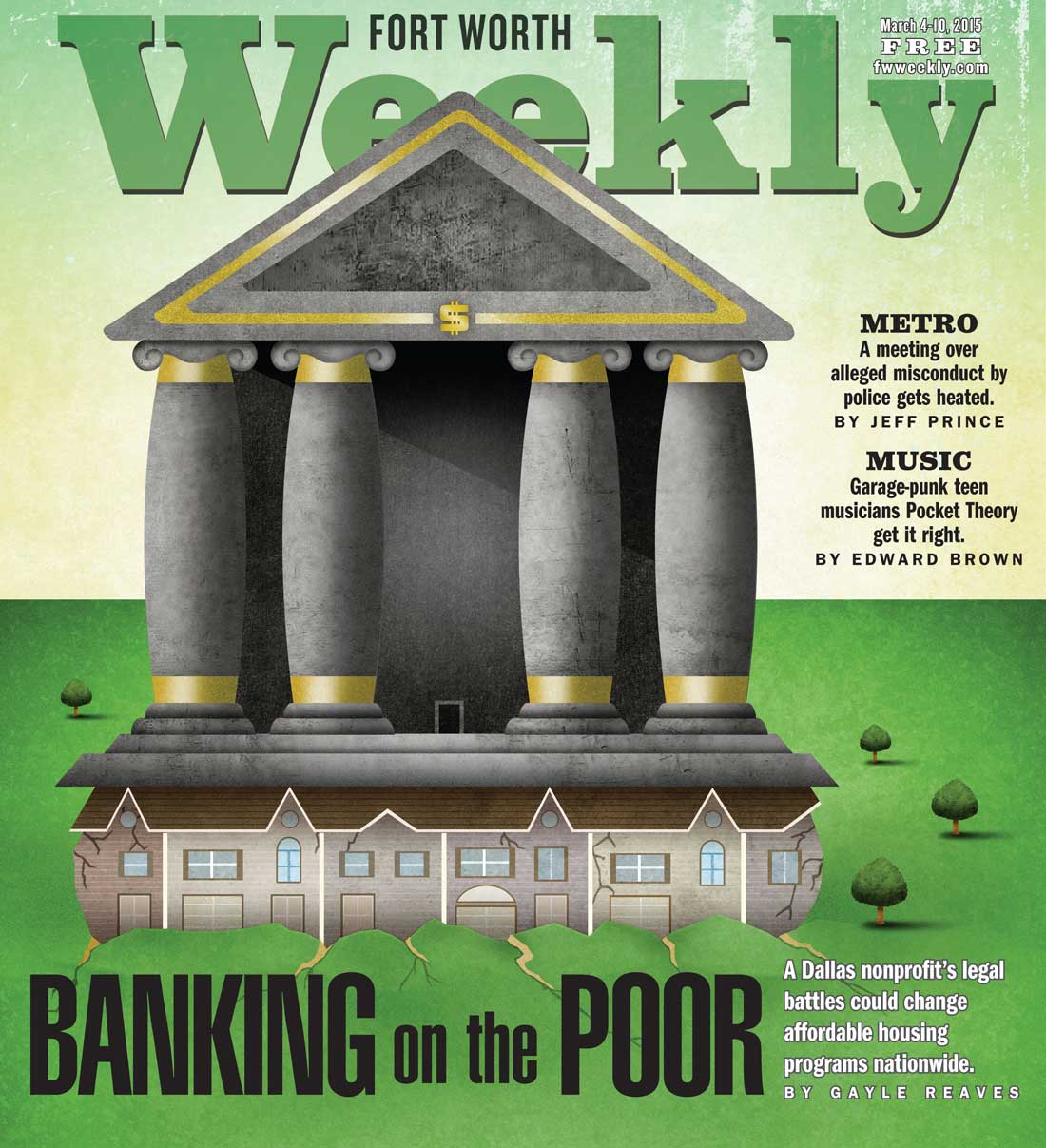

What neither Mike Daniel nor a lot of housing advocates realized at the time, however, was that, just as things were improving in some ways for residents of public housing, another program was coming into play that would drive other minority families who needed help with housing back into poor, problem-filled neighborhoods rather than helping them get out. This time the numbers were much larger. And so was the payoff for a particular segment of the economy: national banks that now hold billions of dollars’ worth of investments in what is called low-income tax-credit housing.

Low-income tax-credit housing is not for the poorest of the poor but for those whose income still falls significantly below the median income for an area. Developers who apply for the program receive a percentage cut in their company’s income tax bill — not a reduction in taxable income but in the actual tax dollars owed. In return, the developer has to offer a certain percentage of units at below-market rates and meet other conditions. Banks and other investors contribute equity and then take advantage of the tax credits. A whole industry has grown up around building and operating tax-credit housing.

In 2008 the vast majority of tax-credit housing units were still being built in high-poverty, high-crime areas, the kinds of neighborhoods where sociologists have repeatedly found that children have a much smaller chance of getting a good education, escaping poverty, and surviving crime to become healthy, productive adults.

And so Daniel, now counsel to a Dallas nonprofit called the Inclusive Communities Project, went back to court. ICP helps low-income families find housing, provides financial help such as security deposits, and works in other ways to improve housing and communities — including by filing groundbreaking lawsuits.

Daniel, with current law partner Laura Beshara, sued the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs on behalf of ICP, over allegations of de facto racial segregation in tax-credit housing.

In 2012, in response to a ruling from U.S. District Judge Sidney Fitzwater in Dallas, the state housing department reformed its criteria for choosing among developers’ proposals, so as to spread tax-credit housing to communities and neighborhoods all over urban areas, giving residents a much better chance at having a decent neighborhood in which to raise their kids.

That suit was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court a few weeks ago. The import of the Supreme Court’s decision, expected by this summer, could go far beyond the bounds of Texas. Then-Atty. Gen. and now Gov. Greg Abbott, in deciding to appeal lower court decisions, is challenging a principle that is part of the bedrock of civil rights litigation in this country —– the idea that racial discrimination can be proved by the results of what is done, without having to show racist intent.

Housing market analysts and other believe the potential impact on low-income housing and civil rights lawsuits of many kinds could be devastating, if the “disparate impact” rule is overturned. U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren wrote a column about it in the Washington Post; civil rights groups submitted an amicus brief in the case.

In August ICP upped the ante again. The nonprofit filed suit against the Internal Revenue Service and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. Together, those two federal agencies oversee the tax-credit program and encourage the participation of national banks. The suit alleges that the tax credit program is perpetuating racial segregation in Dallas and violating the tenets of the Fair Housing Act.

Despite the attention that ICP’s lawsuit against the Texas agency has received, little has been written locally about the nonprofit’s suit challenging the practices of the federal agencies. But the tax-credit housing industry is watching.

Niketa Ramsey isn’t troubled by the way in which reforming the tax-credit housing picture has affected her and her family. The results of the complicated situation are clear to her.

Last summer, after school let out, she and her two younger kids (she also has an adult daughter) left a neighborhood called Sunnyside in Houston’s high-crime Third Ward, for Sunnyvale, near Mesquite. Despite the similar-sounding names of their old and new homes, Ramsey said the two places are worlds apart.

In the old neighborhood, she said, it was “all thugs and drugs.” In the townhome development where she lives now — one of the tax-credit projects built since the Texas housing agency changed its policies — her kids can play outside, her son can ride his bike without having it taken away from him, and he has improved two grade levels in his reading abilities.

“They love it,” she said. “I can see it in my kids’ faces.”

******