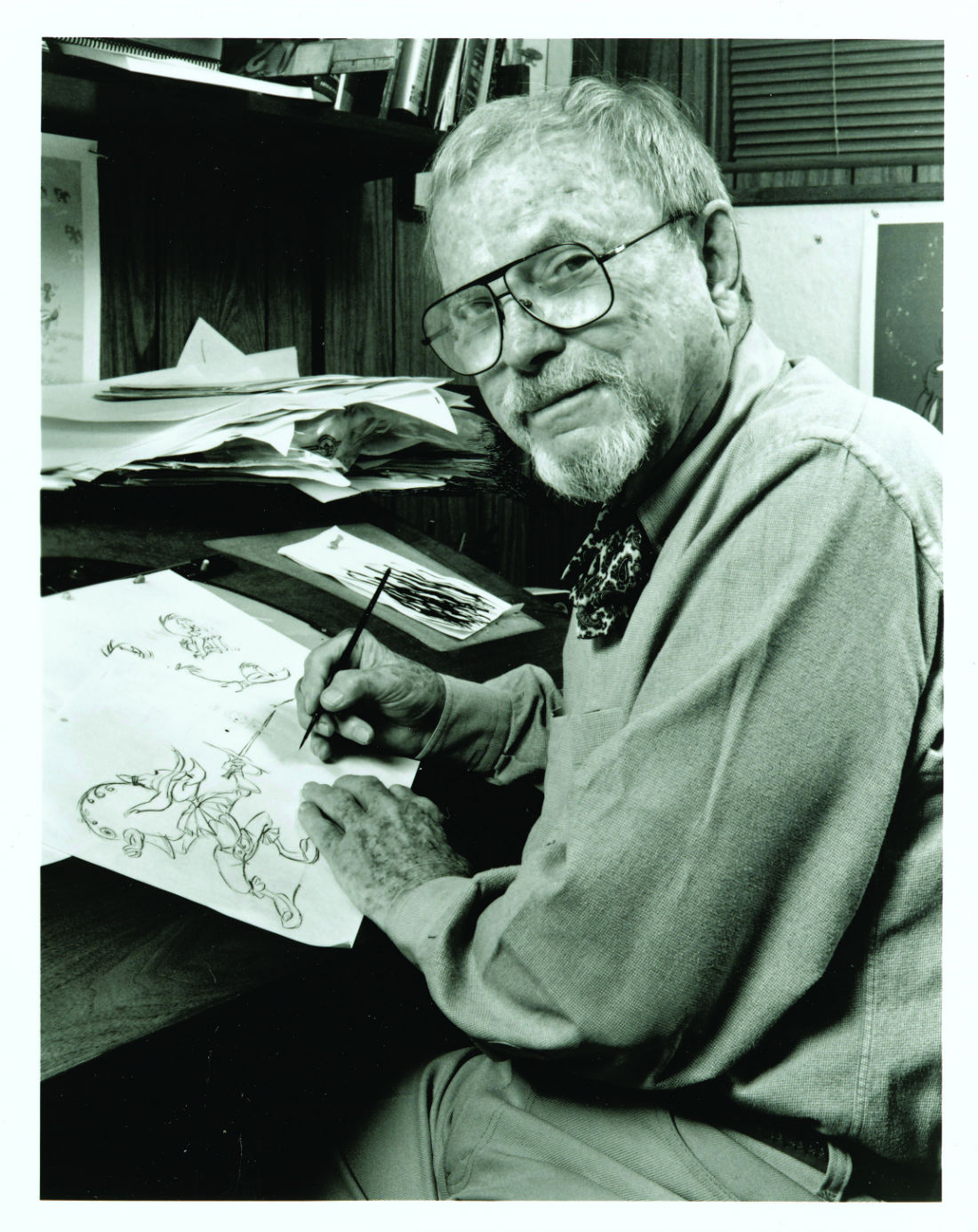

I wore my Bugs Bunny tie to the press preview of the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History’s Chuck Jones exhibit, and I came back with a desire to recap the career of this American comedy master. Many of Jones’ films are on YouTube, so I’ve linked to those where they exist.

The exhibit starts with a clip from two of Tex Avery’s Bugs Bunny shorts, one of which is the Oscar-nominated The Wild Hare. These bear about as little resemblance to the Bugs we know as the first season of The Simpsons does to the current show. Avery was a great artist in his own right, but his Bugs is much cruder both visually and emotionally. FWMSH has sketches on display showing Jones’ refinements to Bugs’ look (long hands and large flat feet, having his ears and whiskers reflect his mood), but the real makeover was in Bugs’ attitude — unflappable, cheerful, sophisticated, with a mischievous streak that can cross over into sadism. (“Ain’t I a stinker?”) That attitude has held up through the decades: Check the brief sequence in 1989’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit? when Bugs and Mickey Mouse both show up to trouble Bob Hoskins’ private detective, and it’s no surprise that Bugs owns the scene.

Much ink has already been spilled on Jones’ love of classical music, seen not only in What’s Opera, Doc? but also in Rabbit of Seville (where Bugs memorably tortures Elmer to the sounds of Rossini’s overture and a bit of Mendelssohn) and Baton Bunny (in which Bugs tries to conduct one of Franz von Suppé’s overtures). Now, other Warner animators used classical music, as did other studios. Disney’s 1940 feature Fantasia had blazed trails in terms of its artistic ambition, but I’d wager that the Warner’s animators took more inspiration from the Marx Brothers’ 1935 comedy A Night at the Opera, puncturing the stuffiness of classical music with anarchic humor.

Parody and pastiche are major tools in Jones’ trade. Hair-Raising Hare has a mad-scientist villain who talks exactly like Peter Lorre, while Broom-Stick Bunny (where Bugs meets Witch Hazel) runs riot with parodies of The Wizard of Oz and Sleeping Beauty. Again, other Warner directors did the same, but it’s worth noting that while Disney’s cartoons took place in distant lands and long ago time periods that created a self-enclosed cultural vacuum, Warner’s engaged with the popular culture. Of course, that same impulse would lead to Space Jam in the 1990s, but I guess risks come with the territory.

One fascinating tidbit I found was a note from Jones saying that when he depicted Wile E. Coyote falling off a cliff, he always took 14 frames between the time that the coyote disappears from our sight and the time we see his impact on the ground. Jones said that he tried it with 13 and 15 frames and never got as big a laugh as when it was 14. One quality that Jones never lost was his exquisite sense of comic timing.

The exhibit features rarities like a clip from High Note, about a musical note on a staff that spotlights Jones’ taste for abstraction. (There’s a delightful moment when a quarter rest symbol turns into a barking dog.) There are also drawings from Now Hear This, a bizarre, British Invasion-flavored short about an Englishman who discovers one of Satan’s lost horns on the ground, uses it as a hearing aid, and hears weird things with it. Besides those, I appreciate the pieces spotlighting the lush background art painted by Maurice Noble.

The show also obliquely mentions the racial stereotypes in Warner Brothers cartoons, and it includes a sketch of Inki, a black Sambo type whom Jones invented for a short called Inki and the Minah Bird [sic]. (Warning: Preceding link contains offensive content and is NSFW. Also, in addition to being racist, the cartoon is scattered, somehow managing to lose track of all three of its characters at different points during 7½ minutes.) Warner’s was not the only studio guilty of racism, and Jones was hardly the worst offender in his own outfit — he had no part in the notorious shorts produced during World War II in which Bugs gleefully doles out slurs to Japanese soldiers. Still, Jones did have one short (Angel Puss) in the Censored 11, the collection of films whose stereotypes about black people have prompted the studio to keep them out of sight. I think we can safely say he was a product of his time. There’s probably a whole history to be written about racism in old Hollywood cartoons. Maybe the Smithsonian’s traveling tribute to Jones wasn’t the place for it, but it would have been interesting to see it addressed. I remember the Modern’s Disney exhibit some years ago that didn’t shy away from the dark side of Uncle Walt’s empire.

Jones’ work declined rapidly once he left Warner Brothers. He collaborated with such creative minds as Dr. Seuss and Norton Juster, but his films lost their old anarchic energy and wit without gaining enough. How the Grinch Stole Christmas has become a holiday tradition, but it’s a sanctimonious bore. The same is true of the Oscar-winning The Dot and the Line. His adaptation of The Phantom Tollbooth (starring Eddie Munster himself, Butch Patrick) is woefully short of Juster’s novel and hamstrung by some lame songs. Jones went to MGM to take over the Tom and Jerry shorts (speaking of racist cartoons…) from William Hanna and Joseph Barbera. You’d think that Tom and Jerry would be perfect for Jones, with Tom’s fruitless pursuit of Jerry being much the same as Wile E. Coyote’s pursuit of the Roadrunner, but he never could recapture the magic.

No, I prefer the Jones of his prime. Duck Amuck isn’t merely a collection of surreal gags, but an unnervingly postmodern piece where Daffy Duck is fully aware that he’s an animated character in an animated movie, and behaves like an actor railing at the people behind the camera who can’t get their act together. In one of the short films in the exhibit, Pixar head John Lasseter describes Jones’ influence on his work, particularly a subplot from Monsters, Inc. (where Sully thinks Boo has been chopped up in the corporation’s garbage disposal) that matches up with the plot of Jones’ Feed the Kitty, in which a large dog is tasked with taking care of an adorable cat. I could have done with more filmmakers and critics describing Jones’ influence on later generations. Nevertheless, it’s hard to argue that the spirit of Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck and Wile E. Coyote haven’t seeped everywhere into our culture. He was a pillar of the great tradition of subversive, wisecracking, irreverent American humor, and he brought legions of children into that tradition. As Bugs would say:

Also in the Considering series:

Song Kang-ho

Keira Knightley

Park Chan-wook

Matthew McConaughey

Bruce Willis

Anna Faris

Kenneth Branagh

My favorite is Michigan J Frog in 1955’s “One Froggy Evening”.