Honeycutt’s 15-member division is one of the largest state toxicology departments in the country. In addition to setting air-quality guidelines, it reviews air and water monitoring data, advises emergency crews after chemical accidents, and provides expertise to agency officials.

“We have probably one of the best toxicology departments in the world,” Commissioner Toby Baker said at a TCEQ hearing last year.

The division’s size remained relatively steady even while TCEQ’s operating budget dropped 39 percent from 2008 to 2013. Its stature rose in 2012, when an agency-wide reorganization put Honeycutt’s department directly under the office of TCEQ’s executive director. The department is now housed on the same floor as the executive director and the three commissioners.

“I love this job,” Honeycutt said in November, during an interview in his spacious office. “This is the job I went to school to learn how to do. I get to sit on the side of the table opposite everybody. One thing we’ve learned is, usually when everybody’s mad at you you’re probably doing your job right.”

Honeycutt, 48, studied toxicology at the University of Northeast Louisiana at Monroe, 30 miles from his hometown. His high school yearbook reveals he graduated with honors.

He stayed at Monroe to get his Ph.D. in toxicology. David Roane, who now chairs the pharmacology department at East Tennessee State University, was an advisor.

“I trusted his work more than most people and found him to be conscientious in a small-town kind of way,” Roane said.

Carey Pope was teaching in the toxicology department when Honeycutt was a graduate student. Pope describes Honeycutt as “the kind of guy who was always the first in line to help you.”

After college, Honeycutt worked three years as a researcher for the Army Corps of Engineers. He joined TCEQ in 1996, when the agency was still known by its former name: the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission, or TNRCC. Critics called it “train wreck.”

By the time Honeycutt was promoted to toxicology division chief, the agency, now TCEQ, was under fire for the way it managed air-quality guidelines. The problem was the haphazard way it set effects screening levels, or ESLs, for thousands of chemicals.

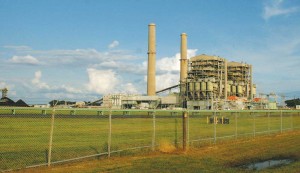

ESLs are critical because TCEQ uses them to draft the air permits it issues to oil and gas production sites, refineries, power plants, and other industries. Companies must show that chemical concentrations at the boundaries of their facilities will meet the ESLs. If they don’t, TCEQ can require them to adjust their operations.

Most chemicals have a short-term ESL (for hour-long exposures) and long-term ESL (for annual average concentrations). For example, the short-term ESL for benzene in 2003 was 25 parts per billion (ppb) of benzene in air. The long-term benzene ESL was 1.0 ppb.

When the Houston Chronicle reported in 2005 that TCEQ’s ESLs were among the least protective in the country, Honeycutt told the newspaper his department was addressing the problem by changing the way ESLs are established.

The agency hired a nonprofit consulting firm — Toxicology Excellence for Risk Assessment — to convene a panel of outside scientists to review the new procedure. TERA was founded by Michael Dourson, a former EPA toxicologist and one of Honeycutt’s close friends. TERA often works for industry and runs a database that has raised the profile of industry-funded risk-assessment values.

Morandi, the consultant, sat on the TERA review panel and said she was comfortable with the TCEQ document. But she said what also matters is how the protocol is applied to individual chemicals.

TCEQ documents its risk assessments in long, complex reports that are posted online for public comment. Honeycutt said he has tried to encourage more feedback by extending the comment period from 60 to 90 days. But few people outside industry have the time and expertise to understand or critique the highly technical documents.

The Texas environmental community tends to rely on a single expert — Elena Craft of the Environmental Defense Fund — to weigh in on risk assessments. Air Alliance Houston Executive Director Adrian Shelley said he often turns to Craft for such help.

Of the 56 comments that have been filed for the chemicals TCEQ has assessed, only one came from the environmental community. About 80 percent came from industry groups, including the American Chemistry Council and ExxonMobil.

Adam Finkel, executive director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Program on Regulation and a former director of health standards programs for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, said environmental groups could help level the playing field by hiring more scientists who understand risk assessment.

********

Welcome to hell, Republican style.

TECQ chief toxicologist, Michael Honeycutt, tells us that there’s nothing bad about ozone alert days. We should just stay inside. We can’t go for a walk, ride a bike, watch our grandchildren play soccer, or work in our gardens. We just have to stay inside and be grateful that Texas lets industry pollute our air.

DFW is the second worst area of the entire USA for ozone pollution.

1200 people die every year in the Dallas – Fort Worth area from ozone poisoning.