Her first royalty check hit the mailbox in 2008, and Becky Ferruggia was excited to see the amount –– about $8,000. Chesapeake Energy landmen had told everyone in her neighborhood that the gas wells would produce for 20 or 30 years. Subsequent checks were more in the $1,000 range, but by year’s end, she’d collected more than $15,000 in royalties on her two-acre lot in an unincorporated area south of Fort Worth.

The next year her monthly check amounts fell to about $500. By 2010, it was $200 a month. Then $100. After that, royalties fell so low that Chesapeake stopped sending out monthly checks, writing annual checks instead. Ferruggia earned a total of $240 in 2012 and about the same in 2013, for an average of about $20 a month (before taxes).

Ferruggia and her neighbors were confused. They’d banded together from the beginning, sought guidance from experts, fought for a fair lease agreement, and used their own attorney to draw up the contract, which forbade Chesapeake from deducting production costs from the royalties. When everyone’s royalties plummeted, the neighbors wondered what had happened. The wells were still pumping, although the figures included on their statements had become so confusing that few people could figure them out. Chesapeake officials, if they responded at all to complaints, blamed falling gas prices.

The neighbors began to suspect that Chesapeake was fudging records and using a subsidiary company to manipulate gas sales and royalty payments, as well as deducting production costs.

“The price of natural gas did fall, but it didn’t fall as much as they said,” Ferruggia said.

She’s now one of thousands of residents across North Texas joining forces to sue Chesapeake for lost royalties.

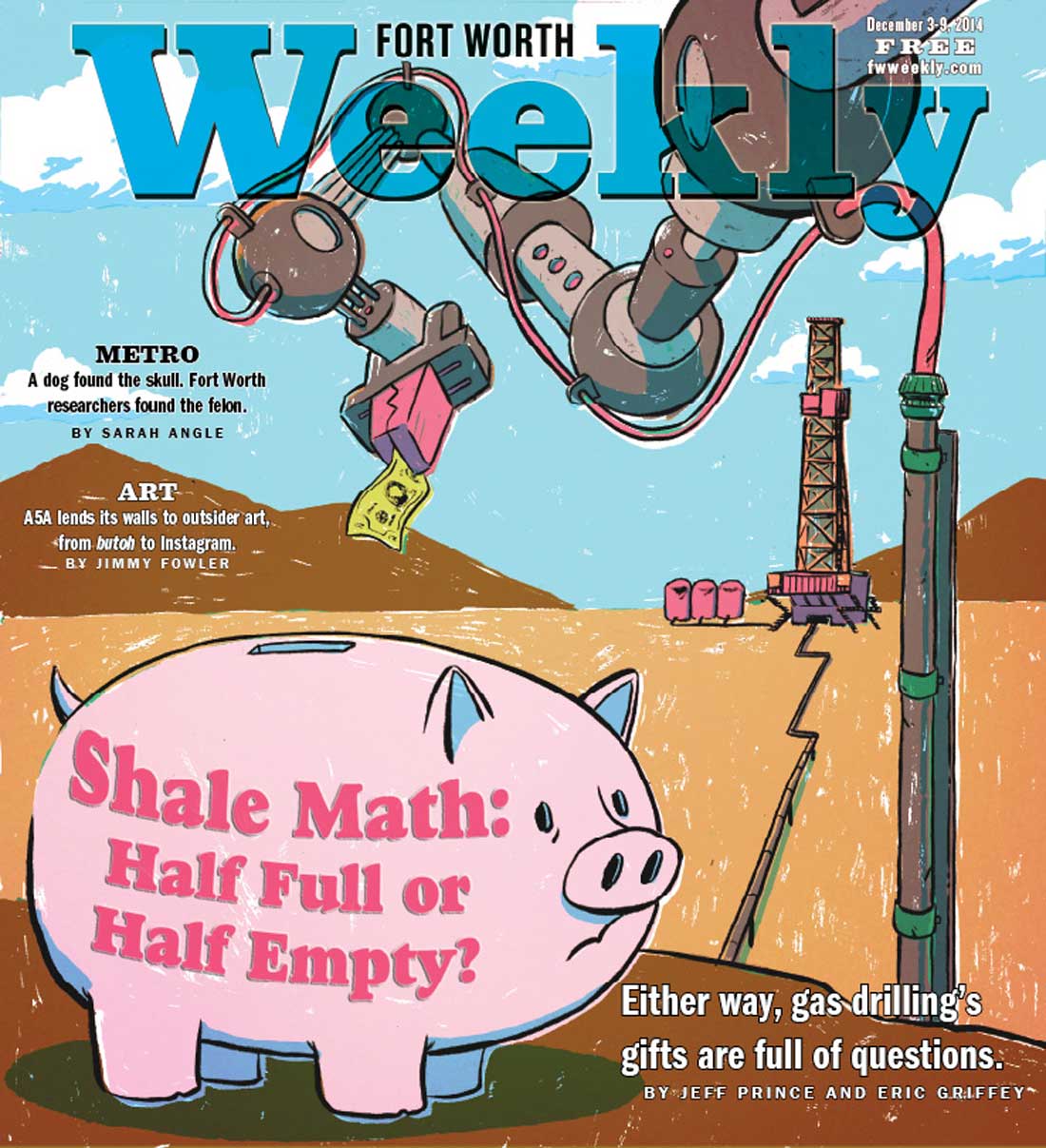

The City of Fort Worth is riding that same boat, earning less than expected in royalties and accusing Chesapeake of jiggering its books. Back when urban drilling was first being discussed, city officials envisioned a gold mine. Some estimated the city could earn $1 billion in gas royalties in 20 years from drilling on city property. The hefty figures being bandied about made urban drilling an easier sell to the public.

Speaking of boats, anyone remember the metaphor that former Mayor Mike Moncrief routinely trotted out to convince everyone to embrace drilling inside the city? Gas riches were “not only going to benefit this generation, but generations to come,” Moncrief was quoted as saying in a New York Times article published on Oct. 27, 2006. “It is without question allowing us to float everyone’s boat higher.”

Moncrief talked a lot about boats floating high back then. Nobody knew all those boats would be drawing water before long. Back then, local motorists could see billboards saying, “If you don’t have a gas well, get one!” People were digging through drawers and filing cabinets, scrambling to find their property deeds, praying they owned their mineral rights so they could get a signing bonus and royalty checks.

A decade after shale gas drilling began, the real numbers aren’t adding up to anything close to original estimates. Moncrief was right to some degree. The money from signing bonuses and royalty checks cushioned the city’s coffers. The influx has helped the city create and maintain parks, airports, and infrastructure.

But the $1 billion estimate appears to have been folly. At the current rate, the city’s shale gas earnings won’t reach half that amount. Many wells produce at a slower rate after just a few years, and experts now say they are likely to peter out far sooner than predicted.

Now cities all around North Texas, from small towns to Dallas itself, are drawing up ordinances making it tougher and more expensive for drillers. Denton recently became the first city in the state to ban fracking. Voters there gave numerous reasons for wanting the ban, including one that hasn’t been heard often –– they’d rather use their raw land for developments to deal with the expected population boom instead of signing it over to energy companies.

These days, accusations, threats, and lawsuits are flowing like a Texas-sized gusher. One local attorney represents more than 10,000 royalty owners in claims against Chesapeake Energy alone, and he anticipates that number will balloon to 50,000 by next year.

Many people and city governments are concluding that the short-term infusion of cash isn’t worth the hit to their city’s environment, property values, or quality of life.

From her backyard, Ferruggia can still see an assortment of wellheads on a nearby pad site. What’s missing, however, is the mailbox money.

“I don’t think we’ve even gotten a check this year,” she said.

********

I’m glad other people in Tarrant County see what is going on, Cheespeake is stealing us blind, I have upwards of 3 acres in within Fort Worth, and as of now we have seen very little maybe 20.00 per1/4acre a month ! Fracking Crooks!!!!!!!!, there is no doubt to anyone with half a brain. I call B**LS**T, on their crimes! They need to be bankrupted for sure!!!!! I’M DONE!!!

🙂 wake up everyone. You can voice your opinion, but if you sleep through sleezy politics, then you are dreaming if you think your opinion matters. Your opinion only matters at your local council meetings. Make your frustrations heard. Do something

gas makes me hard.

All Repukes are hard-headed George, tell us something we don’t know. What do you eat?