Almost every movie deal begins at a seeming impasse. Investors don’t want to promise money unless a bankable star is attached. Stars don’t want to commit to projects until funding is secured. Figuring a way around that chicken-egg scenario is how executive producers earn their fees. The good ones are equal parts sales rep, psychologist, cheerleader, and accountant.

The producing team of Horn and Wilbanks operates in a yin-yang manner, relying on each other’s strengths. Horn is the dashing leading man, charming and articulate, a born salesman and self-promoter. He’s also enthusiastic, regularly cutting off Wilbanks in conversation. Wilbanks rolls his eyes and shakes his head but says little while Horn rattles on, oblivious to the fact he is stepping on his partner’s sentences.

Wilbanks, a paunchy, witty, self-deprecating wiseacre, is just as ambitious as Horn but willing to let his partner take the lead in wheeling and dealing while Wilbanks focuses on writing, directing, and editing. He directed most of the Ghostbreakers episodes, and his creative bent is evident in the slapstick nature of the show, which could be described as Ghost Hunters meets Reno 911 meets The Three Stooges.

“This is of the caliber of Waiting for Guffman,” said Michael H. Price, referring to the Christopher Guest “mockumentary” that earned favorable reviews from critics and filmgoers alike.

Price, the former Fort Worth Star-Telegram movie critic turned author, was speaking to a crowded room at Four Day Weekend theater on a recent evening. A local audience had watched two episodes of Ghostbreakers. Horn, Wilbanks, and Huckabee followed with a Q&A to explain some of their difficulties in getting the episodes into the public eye.

The next week they showed episodes to Cleburne residents on a projector in the backyard of Wilbanks’ parents’ house. The shows are also available for internet download.

Horn and Wilbanks expected their TV series to give them cash flow for other projects, if not make them rich. Greco, who was replaced as host of Cheaters in 2013 after 10 years with that show, hoped Ghostbreakers would advance his acting career. Primary investor Stephen Bailey, who works as a waiter at Del Frisco’s Double Eagle Steakhouse, hoped to cash in on the paranormal TV craze, make a quick buck, pad his resumé, and move to the next project.

Instead, they’re all hustling to sell a show more than a year after shooting wrapped. Domestic sales haven’t panned out. Now they’re soliciting overseas outlets and hoping to capture a foreign audience, develop a buzz, and, in turn, interest American distributors.

“Ghostbreakers is a mission,” Horn said. “This will take up most of my life until it’s out.”

He’s still juggling other projects to help pay the bills, including acting gigs. One of his recent feature roles had him being eaten by beautiful strippers who also happen to be cannibals. The Ladies of the House premiered in April at the Dallas International Film Festival.

Horn has been acting locally since childhood and has appeared in hundreds of commercials, theater productions, training videos, TV shows, and movies. He even auditioned to be Barney on the popular childhood series Barney & Friends, but didn’t dance well enough to get the job.

“That costume weighs 90 pounds,” he said.

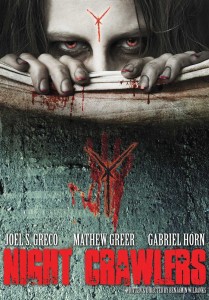

Despite more than 70 credits on his IMDb internet profile, he’s still relatively unknown. In addition to Ghostbreakers, Horn helped create Night Crawlers (2008), which starred himself and Greco and was written and directed by Wilbanks. And Horn produced and starred in Carried Away (2009), which was shot partly in Fort Worth.

Huckabee attended the Night Crawlers movie premiere in Fort Worth in 2008, liked what he saw on the screen, and befriended Horn and Wilbanks at an after-party. He asked Horn to help find financing for Carried Away. Horn and Wilbanks had made Night Crawlers for about $60,000 and filmed it mostly around Glen Rose.

“I loved the movie,” Huckabee said. “It registered in my mind –– that’s a low price for a professional, entertaining product. Ben did a great job writing and directing. I liked the spirit and tone of it, and I liked this group of people.”

Horn and his wife, Jennifer Floyd, signed on as producers for Carried Away and set out to find money. Huckabee nabbed local filmmaker James Johnston as a creative producer to help put together a cast and crew.

Before long the first bill came due –– $10,000 to pay a casting director. But Horn and Floyd hadn’t found any investors. Huckabee dipped into his savings. When his wife died in 2006, he’d taken a loan out on their Los Angeles house, put it up for sale, and moved back to his hometown of Fort Worth. Huckabee paid the casting director out of his own pocket. He’d once read an interview with director Francis Ford Coppola, who said he rarely had a film financed completely when shooting began; he counted on people to glom on during the shoot and give him money.

“I was inspired by that,” Huckabee said. “I like the wildcatting aspect of it.”

Halting the movie after $10,000 had already been spent seemed counter-intuitive to Huckabee, so he forged ahead.

“That was a no-turning-back stage,” Huckabee said. “We had a start date [for filming], but no money had come in by then. I dipped deeper into my loan. Thirty days after the first day of shooting, I had spent all of my money.”

After he’d burned through his $190,000 loan, he emptied his checking account. Cashed in his retirement account. Maxed out his credit cards. Borrowed from friends and family. By the time the movie was finished, he’d spent $275,000. Five years later, he’s still struggling, renting out a room in his small house in Fort Worth to help pay bills, and finding the occasional rewrite job for a small paycheck.

“Gabe starred in the movie and made a great contribution there, but as far as the money, gosh –– how do I put this? –– I don’t think he raised any money at all,” he said.

Huckabee still admires Horn despite the financial failure of Carried Away. He entrusted Horn to find the money needed to make the movie, and that’s what happened.

“He raised the money –– he raised it from me,” Huckabee said with a rueful laugh. “I call it the best and stupidest thing I ever did in my life. On an economic level it makes no sense, but I see Carried Away as a successful work of art that will exist long after I’m gone, and I’m very proud of it and pleased that I was conned into making it by Gabriel Horn.”

None of the producers got paid, including Horn. Despite losing his nest egg, Huckabee said he’d gladly charge the front lines again with Horn.

“He’s a mediator, mild-mannered like myself, and a pleasure to work with,” Huckabee said. “Always has a great attitude, he’s always putting out fires with other people who are losing their heads, he’s a good flak catcher who always thinks on the bright side.

“To be in the movie business is a con game. You’re selling dreams, ephemera, phantasms, shadows on a wall. They’re often elusive. The money is always elusive.”

********

The Four Day Weekend screening of Ghostbreakers also presented a couple of movie shorts by local filmmakers. Brett Bentman’s Slow Wave was stylish, intriguing, and well made despite a budget of only $3,500. The Dallas-based writer and director is like hundreds of other local filmmakers, eschewing the Hollywood hamster cage in favor of finding his own financing, marketing, and distribution.

Bentman, 33, has made nine shorts and two feature films in 10 years, often combining crowdfunding campaigns with money from a list of private investors he’s developed.

“We did an Indiegogo campaign for this film, but I secured about 85 percent of the funds through private investors who have followed my career over the last 10 years,” he said. “Eventually you have a book of people who are passionate about your films and passionate about you, and then you can shift away from crowdfunding.”

Crowdfunding donors are content to get free movie screenings and autographed DVDs. Private investors usually want more. “The perks get a little [bigger], the stakes are higher. Maybe they want tickets to festivals,” he said.

The larger the stakes, the less likely an investor will step forward without expecting a financial return. The most successful filmmakers are often as business-oriented as they are creative. Raising money is step one.

“We’ve done it really well, but it’s something you have to take even more seriously than the film itself. But nobody wants to do that,” Bentman said. “Nobody wants to beg for money, but that’s what you’re doing.”

The screening was hosted by Endeavor Cinema Group, a nonprofit organization that supports the development of North Texas independent filmmaking. The group’s president, Carlos Aguilar, isn’t a filmmaker himself, but he appreciates folks who gamble bank accounts and reputations (and their mental health) in fanatical attempts to create moving pictures.

“We’re helping to facilitate the motion picture agency through screening, networks, mixers, and whatever,” he said. “We have an introductory program we put together and are actually going to be producing our own short films, documentaries, animations, music videos — everything. They’ll be fully funded.”

Bentman is the first recipient of one of the grants. He’s been chosen to write and direct a film short with a $3,500 budget provided by Endeavor Cinema. Production begins Dec. 12, using local actors and crews.

“The goal is to help build an industry,” Aguilar said. “At this point I don’t feel we have a strong indie film industry [in Fort Worth]. We have the resources, but somebody has to take the reins and give everybody direction.”

There is no shortage of filmmakers, actors, crew, or material. What’s mostly missing here and everywhere else are the deep-pocketed investors willing to put up money in a risky business.

Bailey, the North Richland Hills resident who financed Ghostbreakers, is a former stockbroker with a master’s degree. Naturally, he’s eager to sell the show and generate revenue. If they sell 20 episodes to a major media company overseas for $50,000 each, that would generate $1 million and put them in the black. If they found an American distributor, they could be rolling in the greenbacks for a while.

“They had the talent to make something good, and that’s what happened,” Bailey said. “We made a show without having a sale in place ahead of time, which may have been a mistake. I hope not. TV is a fickle world. Make a show on spec and sell it, we look brilliant. Make a show on spec and don’t sell it, we look stupid.”

********

Hustling and jiving for a living might sound sketchy to nine-to-fivers working at traditional jobs. But the manner in which Horn, Wilbanks, and Huckabee scrape by is as common as popcorn in the movie industry.

“It is a hustle –– with big rewards,” said Greg Mansure, a film, TV, and digital media professor at Texas Christian University. “You only need one film to make a million dollars. It’s like Vegas.”

Mansure, who spent 20 years in the film industry as a cinematographer, has seen several episodes of Ghostbreakers and described it as a “very valid product, beautifully produced and well shot.”

Horn and Wilbanks might have a better chance of getting rich at a craps table. In addition to battling a closed society of industry gatekeepers, indie filmmakers today face stiff competition in their own ranks. As Ghostbreakers has proven, even a quality product isn’t a guaranteed sell.

“A lower-middle-class kid in Kansas can buy a camera and laptop and make a feature good enough to play at the Movie Grill,” Mansure said. “Content is always an issue, and that’s what the hustle is about –– who’s got the most intriguing content.”

And who’s got money.

Reading Rainbow exemplifies the evolution toward indie TV. The show that encouraged kids to read was shown on public TV from 1983 to 2009. Actor LeVar Burton hosted the show, and in 2012 he developed a Reading Rainbow app for download on iPad; it reportedly became the most downloaded educational app at the iTunes store. A crowdfunding campaign earlier this year raised more than $5 million to get the app included on other streaming devices such as smartphones.

Bentman loved the reading show when he was a kid, and he loves living in an era when fans can save a show even after networks bail out.

“These things can live on because of the power of crowdfunding and the independent nature of things,” Bentman said. “I couldn’t be a filmmaker if I was just living in Dallas and hoping somebody in Los Angeles would give me money for a film.”

The indie nature of today’s film scene suits Wilbanks, who’d just as soon write, direct, and pay for his projects without any reliance on Hollywood. Horn, though, keeps a foot in both camps, working on indie films while also making regular trips to Hollywood to try to put together major movie deals. Their styles and approaches might differ, but they’re unified in at least one thing –– neither plans on giving up.

“We strategically avoided a backup plan,” Horn said. “I remember telling that to my mother when she’d say, ‘Can you please be an attorney now?’ I’d say, ‘I’ll play one on TV.’ It wasn’t until I did a Southwest Airlines commercial and showed her a check for $4,200 that she said, ‘You’re an actor!’ ”

Now he’s waiting to generate the paychecks that will prove to everyone that he’s an accomplished executive producer. The best thing to do is keep plugging away, but also to stay cool, he said.

“There’s one main thing Hollywood is disgusted by, and that’s desperation,” he said. “This is the dichotomy of my life. I take meetings with one of the most powerful agents in the world, and I’m sleeping on a couch.”